Private TV channels may sometimes jilat the government, and the reason go back to the 1980s

- 423Shares

- Facebook388

- Twitter6

- LinkedIn7

- Email10

- WhatsApp12

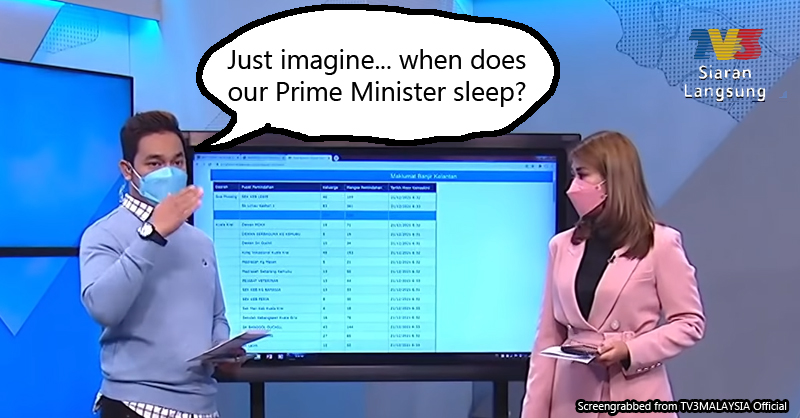

If you’ve been on social media lately, you’ve probably realized that not much good had been said about the government’s response to the flood, and those who defended the gomen had been mercilessly branded as cybertroopers by the displeased netizens. Caught in the crossfire recently was a TV3 host, due to one of his statements during a Malaysia Hari Ini (MHI) episode (21 Dec) that discussed the recent tragedy:

The same host regarding our pm’s busy schedule

Full video: https://t.co/qsIzSf2dmQ pic.twitter.com/4vUNE4ggt1— Azrin Ahmad (@azrinsunbae) December 21, 2021

If you didn’t watch that clip, the hosts were essentially discussing how busy the Prime Minister’s schedule was in visiting affected areas, and the guy wondered aloud when does Ismail Sabri get any sleep. However, as people on Twitter had pointed out, the flood victims had a much harder road to hoe, and Ismail Sabri’s visits was totally unnecessary. So perhaps unsurprisingly, this display of misplaced empathy was met with ridicule, cyberbullying threats to the host, and accusations of TV3 sucking up to the government.

By now, it’s an open secret that some media outlets are seen as the government’s mouthpiece, but how many of them are actually owned by the government, and for how long already? We’ll read some papers on the matter and try to give you a general idea of the situation, starting with perhaps an ironic fact…

TV3 was the first ‘private’ TV station in Malaysia

The history of TV in Malaysia is a relatively short one, and it officially began on 28 December, 1963 by Televisyen Malaysia, which would later became Radio Televisyen Malaysia (RTM), a body under the Ministry of Information. When it first started, television was a single network broadcasted in black and white (we only got color TV in 1978) called Rangkaian Pertama, and its success led to a second channel (Rangkaian Kedua) in late 1969. These channels would later be known as TV1 and TV2, and according to the ministry’s mission statement, these channels function to:

- propagate government policies,

- promote Malaysian art and culture, and

- provide education, general information, and entertainment.

For more than two decades, the government held a monopoly on TV channels, until Mahathir’s Privatisation Policy entered the chat in the 1980s. In case you’re not familiar with that policy, basically the government realized that they’re handling too many things, so to save money and grow the economy, they decided to let go some of the things they’ve been handling to companies outside the government. Private companies can now enter where they’ve never entered before, and one of those places was TV broadcasting.

One of the first TV companies to be privatized was Sistem Televisyen Malaysia Berhad (STMB), which operated TV3, Malaysia’s first ever private television channel. However, TV3 seems to only be private in name. A paper noted that STMB was essentially ‘a joint venture of five companies … closely linked to the ruling political parties‘, while another revealed that 40% of STMB’s stock was held by Fleet Group, an UMNO holding company. The other four were Utusan Melayu Group, an UMNO-controlled newspaper; Maika Holdings, owned by MIC; Daim Zainuddin, Finance Minister around that time; and another group chaired by Syed Kechik.

So despite being private, TV3 had been run by people from the ruling government since back then, and this situation became the norm rather than the exception…

Most TV stations since then can be linked back to the government

[Most of this section refer to three works, which are listed at the end of this article.]

In the following decades, many other private TV stations came into being, but it seems that most of them are linked to politicians in one way or another. As one source remarked, it was pretty evident that in the privatization of TV stations at least, the process had been selective – companies seem to be awarded licenses based on who owns them. Gomez (1994) noted that the Privatization Policy mainly benefited two parties: political leaders, and businessmen close to them.

“…since Privatization in most cases did not even involve the formality of an open tender system, many beneficiaries were chosen solely on the basis of political and personal connections.” – Gomez E.T., as quoted in “Communication Technology and the Television Industry in Malaysia” (2006).

This seems to be the case for the terrestrial television channels. In 1995 for instance, a short-lived channel called MetroVision popped up. The tender to operate this channel was awarded to a consortium of four companies, two of which have clear political ties: Utusan Melayu Group and Melewar Corporation, the latter chaired by Tunku Abdullah, a royalty of Negeri Sembilan and close associate of Mahathir.

NTV7, which came about in 1998, was originally chaired by Mohd Effendi Nawawi, then a member of BN and later the Minister of Agriculture after the 1999 General Election. When Channel 9 was established in 2003, and it was owned by a Tan Sri Rashid Manaf (51% share) and Datuk Muhammad Mustafa (49% share), the latter being the former chairman of Medan Mas Sdn Bhd, which was the broadcast license holder of MetroVision. Finally, 8TV came in 2005, and the license to operate it was given to a company called Media Prima Bhd.

Media Prima came from a restructuring practice following the downfall of mainstream media popularity in the 2000s, and it bought out 100% of TV3 and 43.5% of New Straits Times Press (NSTP) at its inception. By the end of 2005, it had acquired Channel 9 and ntv7, and including the newly-established 8TV and the newspaper NSTP, it became the biggest listed media company at the time. However, as you’ve probably guessed, it also had political ties: the first Executive Director appointed was Kamarulzaman Haji Zainal, the former press secretary of then Prime Minister Abdullah Ahmad Badawi.

Seemingly business-oriented channels have links to politics as well. The short-lived Mega TV of 1995 was Malaysia’s first subscription-based TV network, and it was owned by Cable View Sdn Bhd; of which 30% belonged to the Ministry of Finance, while another 5% by Sri Utara, the investment arm of MIC. With the launch of satellites MEASAT I and II, Malaysia’s first satellite television, ASTRO, arrived in 1996. Astro is then 85% owned by Binariang Sdn Bhd, and 15% by Khazanah, the Ministry of Finance’s investment arm. Binariang itself was owned by Ananda Krishnan, a prominent businessmen with close ties to previous PM Mahathir.

We’ve probably missed a few stations, but you probably got the point by now. So now you might be wondering…

Wah so scary! Is CILISOS owned by the gomen oso??!? Who can I trust then?

Hah! We wish. It should be noted that just because a media company is owned by political parties, it doesn’t mean that they will be 100% pro-gomen or otherwise: not every TV host expressed their concern over Ismail Sabri’s sleep schedule. Besides, ownership is just one form of control the government has over the media. Even if they’re not owned by any political entities, any media company – not just TV channels – still can’t go too far with reporting or saying certain stuff to the public, due to some laws we have that can be abused to shut up non-government-friendly pieces. For example,

- Section 233 of Communications and Multimedia Act (CMA) 1998 prevents any story that’s ‘obscene, indecent, false, menacing or offensive’.

- The Sedition Act 1948 prevents anything seditious from being published, which essentially includes anything that involves questioning the government.

- The Official Secrets Act 1972 can practically turn any document into an official secret, making talking about them illegal.

So whether or not a media company is owned by the government, in a sense they’re still controlled by the government to some extent. It has been a problem for a very long time already, and although some things have improved over the years, we still have quite some ways to go.

So which news outlets do I believe then? Well, CILISOS, obviously. For now, that’s a question you’ll have to figure out on your own. In this day and age, we can choose from a wide selection of reputable news providers, and they all mostly report the same things anyway, albeit with their own flavor and slant. Read more than one version of an issue. Check their sources. See what the people on social media are saying about it. Read between the lines, and figure out for yourself what you want to believe. Or, you know, abandon everything and watch Netflix or sumn.

List of references from before:

- “A Broadcasting History of Malaysia: Progress and Shifts“. Asian Social Science, 2013.

- “Who Owns the Media: Global Trends and Local Resistances“. Zed Books, 2004.

- “Communication Technology and the Television Industry in Malaysia“. Juliana Abdul Wahab, USM, 2006.

- 423Shares

- Facebook388

- Twitter6

- LinkedIn7

- Email10

- WhatsApp12