Hundreds of Tamil women left Malaya to fight for India in WWII. They never got there

- 211Shares

- Facebook145

- Twitter8

- LinkedIn6

- Email11

- WhatsApp41

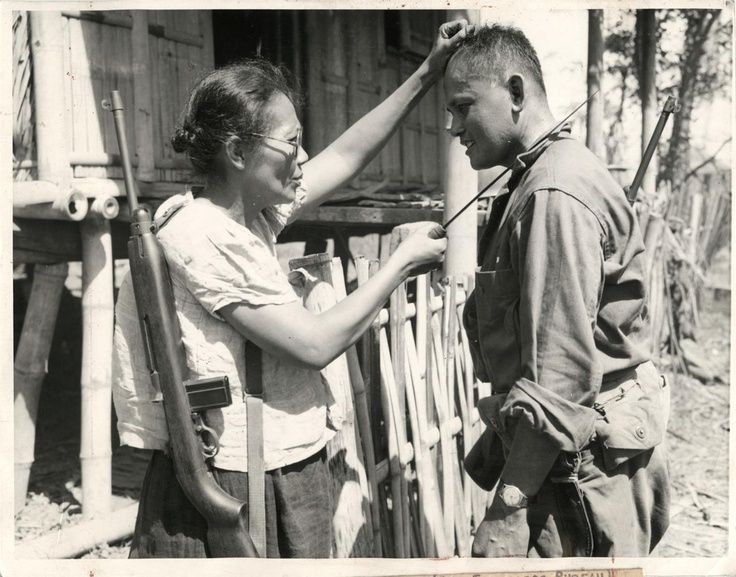

Although women were more known for working the factories in WWII, there are countless stories of women on the frontlines. To name a few, there’s the legendary Soviet sniper Lyudmila ‘Lady Death’ Pavlichenko who racked up an impressive 309 kills, as well as the Filipina guerrilla fighter Nieves Fernandez, who was such a thorn in the side of the Japanese that they placed a 10,000 peso bounty on her head.

But there is a lesser-known story of a whole regiment of women who took part in India’s fight for independence during WWII; many of whom actually came from Malaya. For this, we have to go all the way back to 1942, during the height of the war…

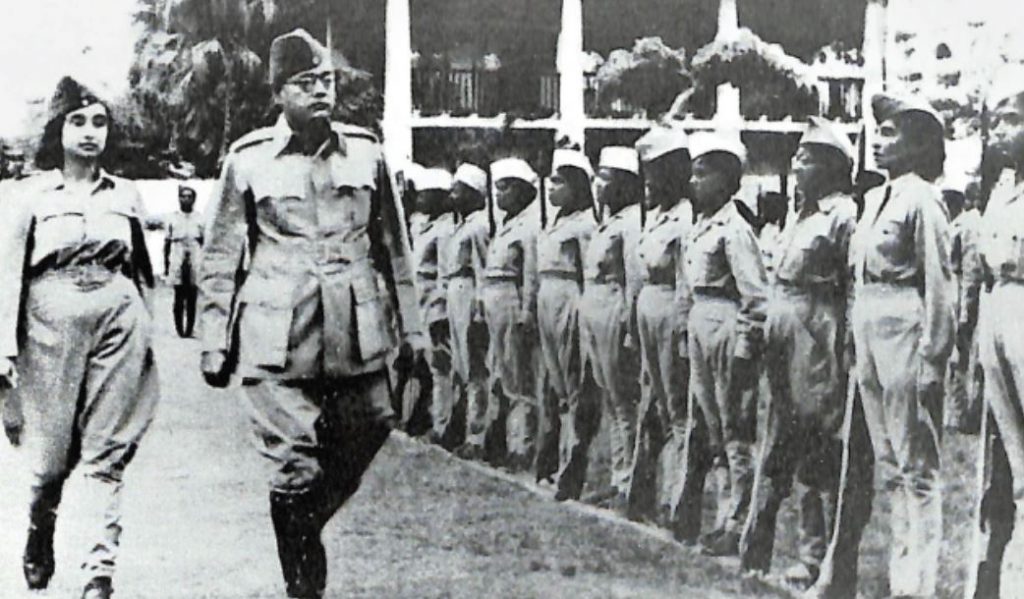

It all started with a pro-Nazi Indian militant named Subhas Chandra Bose

Born in Bengal in 1897, Subhas Chandra Bose was heavily influenced by the writings of Mahatma Gandhi, but soon grew disillusioned by Gandhi’s non-violent philosophy, believing that violence was the only way to secure Indian independence from the British.

Being from Bengal, one of the earliest states in India to recognize female emancipation and education, Bose also believed women should be given their shot at joining the men in the fight for independence. This would play a key role in the fates of overseas Indian women everywhere, especially in Malaya and Singapore, but we’ll get to that in a bit.

Anyway, because of his radical ideologies, he was placed under house arrest in 1940, but later escaped house arrest a year later, fleeing to Germany, where he hoped to get the help of Adolf Hitler in kicking out the British from India. Having similar ideologies, the two warmed up very quickly, and he quickly gained Hitler’s respect. However, Hitler was unwilling to send German troops to aid Bose’s efforts in India, due to logistics and his focusing on the main conflict in Europe and the Pacific:

“We have no intentions of reaching your frontiers in the near future. One should show one’s strength only over the area covered by the tip of one’s sword.” – Adolf Hitler, from ‘Mahanayak Subhas Chandra Bose: A Novel’ by Vishwas Patil

Meanwhile, Singapore had fallen to the Japanese, and many of the Indian soldiers serving under the British had been taken prisoner. These soldiers would be encouraged by the Japanese to become a part of the new anti-British Indian National Army (INA). After the commander of this new force was sacked for insubordination, they needed a new leader, and Bose returned from Germany to fulfil this role. With Hitler being non-committal to the Indian cause, it became clear to Bose that Indians could only rely on themselves. He would immediately get to work, recruiting Indians from all walks of life to fight for the cause.

Guided by the principles of Bengali female empowerment, he decided to maximize Indian (wo)manpower by forming an entire all-female regiment within the INA, naming them the Rani of Jhansi Regiment after an Indian Rani (Queen) who was martyred during the 1857 Revolt against the British. Bose chose this name as he was inspired by a quote from an Englishman, who wrote after the conflict:

“If there had been a thousand women like the Rani, we could never have conquered India.”

This new female force included women from Malaya, Singapore, and Burma

In a rallying speech at the Padang in Singapore, Bose called on Indian women in Malaya, Singapore, and Burma to join the struggle:

“This must be a truly revolutionary army… I am appealing also to women… women must be prepared to fight for their freedom and for independence… along with independence they will get their own emancipation.” – Subhas Chandra Bose, 1943

This call reached Tamil Indian women in Malaya, who often had to endure sexual exploitation and poverty in their jobs on rubber plantations. And so, despite these young women having never even seen India, many jumped at the chance to escape colonial bondage; reportedly some 1,000 Indian women signed up to the Rani of Jhansi Regiment.

These women came from diverse backgrounds: an estimated 80% were uneducated (mostly wives and daughters of rubber plantation workers in Malaya), while only some 20% were educated; their captain, Lakshmi Sahgal, was a doctor in Singapore. Yet despite the gulf in class, Bose rejected the caste-based separation of traditional Indian society, ordering all recruits to eat and live together; even making them learn Hindustani as the common language among the soldiers:

“We used to chat and sing songs. We unitedly stood for a free India. We finished our training and never once thought of returning home. I still think about those times.” – Lakshmi Krishnan, former Section Commander in the Rani of Jhansi Regiment

And, in line with Bose’s egalitarian policy, his Ranis were given the same combat training as the men, carrying out rifle, grenade, bayonet drills, and even took part in advanced jungle warfare training. Although the Ranis were intended to enter the Gangetic plains of Bengal via Imphal, the Battle of Imphal ended in disaster for India, and the regiment was never officially deployed to the frontlines as combatants (as far as we could find). Still, some women from the regiment had close shaves with death, such as when a bomb was dropped on their camp, and when the British opened fire on them during a shifting of camps. Many served as nurses, and treated the wounded on the frontlines in Burma.

After the war, the Rani of Jhansi Regiment was mostly forgotten by historians

True to his word, the women of the Rani of Jhansi Regiment were allowed to return home to their families, with many of the educated officers turning to professional lives. Unfortunately, it’s not known what happened to many of their members; some of the uneducated ones were repatriated to India, an unfamiliar country, and died in poverty, with some never realizing the significance of their struggle due to their illiteracy.

However, interest in their stories have resurfaced in recent years, and even the Indian government has acknowledged them, such as with Malaysian ex-member Anjalai Ponnusamy, who recently passed away at the ripe old age of 102 years.

Anguished by the passing away of the distinguished INA Veteran from Malaysia Anjalai Ponnusamy Ji. We will always remember her courage and inspiring role in India’s freedom movement. Condolences to her family and friends.

— Narendra Modi (@narendramodi) June 1, 2022

Although they remain an obscure (and perhaps controversial, due to their alignment in WWII) part of history, the Rani of Jhansi Regiment is still a Malaysian story that deserves to be told.

- 211Shares

- Facebook145

- Twitter8

- LinkedIn6

- Email11

- WhatsApp41