How Malaysia slowly killed its own rice industry

- 3.6KShares

- Facebook3.3K

- Twitter40

- LinkedIn20

- Email53

- WhatsApp163

80kg of rice per person. That’s how much the average Malaysian polishes off in a year. Whether it’s nasi lemak, chicken rice, or the classic end-of-the-month saviour – rice with kicap (don’t pretend you’ve never had it); rice isn’t just food. It’s practically a national identity.

With that level of consumption and the iconic paddy fields of Kedah doubling as both a tourism draw and Instagram backdrop, you’d think we’d be swimming in locally grown rice, right? Wrong. The truth of the matter is, about 30% of the rice we eat is imported.

Yup, despite all that land and our various nasi dishes, we still can’t grow enough to feed ourselves. So what’s the story? Is local padi not good enough for our atas tastes, or is there a bigger issue at play?

Turns out, the answer’s a bit grainy. To begin with…

We got the fields, but not the yields

Very simply put, food security is everyone having access to safe and nutritious food at all times. So, the more dependent you are on other countries for supply, the less food security you have.

And Malaysia has a problem with food security despite having more than enough land to grow our own food. In 2022, Malaysia spent around RM2.67 billion importing rice alone.

It’s not a secret either. The Prime Minister’s Belanjawan 2025 speech literally spells out the problem:

“One of our significant weaknesses is the high dependence on food imports despite having fertile land and the capability to enhance the nation’s food security.” – Quoted from page 82 of Belanjawan 2025

If you’re wondering why this is so important, 2008 gave us a rude wakeup call. The 2008 rice crisis was a chap fan of different events all over the world that saw major exporters like Vietnam and India stopping exports to secure their own supply. This caused global rice prices to shoot up. Malaysia being a net importer, scrambled not only to ensure supply but ALSO subsidized the higher prices. The cost of these subsidies? RM70 million.

But how did our yields get so low? Well, it’s definitely easy to blame the weather.

Did you know rice is notoriously picky about its environment? Just a 1–2°C increase in temperature can slash harvests by nearly half. And if the heat doesn’t get us, the floods will.

Paddy farming is seasonal, so one bad flood can wipe out an entire year’s harvest. To put this into context, the recent floods in Kedah and Perlis submerged over 6,000 hectares of paddy fields, wiping out an estimated 30,000 metric tonnes of crops worth over RM50 million. That’s enough rice to feed the entire country for four whole days!

But the weather can’t be bad every year, right?

The roots of Malaysia’s rice struggles run deeper than our sawah padi

One of the key hurdles in Malaysia’s rice industry stems from its past reliance on a monopolistic system.

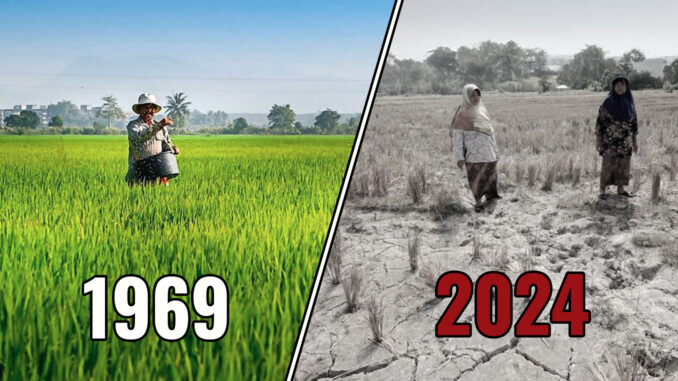

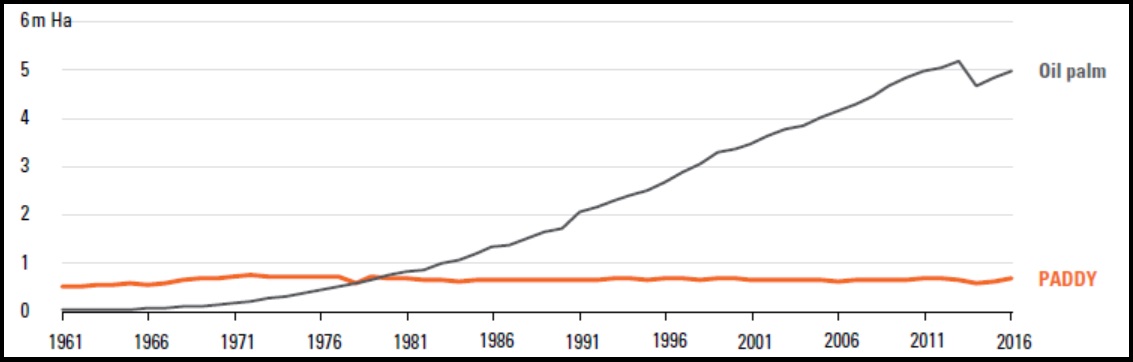

We’re going back to Om Puteh times here. Before independence, our food policies were all about feeding the colonial masters’ coffers. The focus was on plantation crops like rubber and palm oil, while rice farming got little to no support. Back then, the rice self-sufficiency level (SSL) was below 50%, and tapioca was the poor man’s staple.

Post-independence, things started improving. The Malaysian Agriculture Research and Development Institute (MARDI) was set up to lead research on crops, including rice.

In the ’70s, the government doubled down on rice security with subsidies, fixed prices, and a guaranteed buyer for farmers through the National Board of Paddy and Rice (now BERNAS). Projects like the Muda Irrigation Scheme – a system that helps control water flow for paddy fields in parts of Kedah and Perlis – boosted production, and Malaysia slowly became more self-sufficient.

But heavy subsidies and BERNAS’ monopoly created a bubble. Meanwhile, MARDI had a near-total grip on paddy breeding work. And sure, MARDI did play a role in developing rice varieties, but the problem was the lack of competition. With no alternative sources of innovation, progress was limited.

So while prices of rice were kept stable for the most part, farmers had little incentive to innovate. The industry stagnated while our neighbours like Thailand and Vietnam embraced modern farming methods and put R&D into developing new strains.

By the ’80s, the World Bank called Malaysia’s rice industry “unsustainable“.

Importing rice is actually cheaper than growing our own

As mentioned, Malaysia spent around RM2.67 billion importing rice in 2022. In comparison, the government pumped RM2.6 billion into subsidies, incentives, and support for our local paddy and fishing industry in 2023.

For 2025, the government continues to put their money where our mouths are, with a whopping RM2.78 billion in subsidies and incentives to give our paddy farmers (+ fishermen!) the support they need.

View this post on Instagram

Among the things they’ve come up with for farmers are:

- Paddy price subsidy scheme: Now bumped up to RM500 per metric tonne (from RM360)

- Minimum rice price: Upped to RM1,300 per metric tonne (up from RM1,200)

- Disaster relief for farmers: RM50 million to cover up to 50% of crop losses from floods and other disasters

- Support for dryland paddy farmers: RM50 million set aside for them too

- Takaful Scheme for paddy crops: RM50 million to cover 240,000 paddy farmers

- Fertiliser procurement initiative: RM50 million for farmers to choose their own fertilisers

- Optimising land use: RM150 million investment to maximise land for crops and livestock

That’s a whole lot of points, but the short of it is that they’re giving farmers the full package. All those efforts address the big bads of rising costs, climate change, and global supply chain hiccups to lay the foundation for a more secure food system.

It’s a rough comparison but it shows that we’re spending more to support local rice than we are just buying it from abroad.

In short – berspending-spending sekarang, bersenang-senang kemudian.

But here’s the thing: fixing Malaysia’s rice issues isn’t going to happen overnight. Many of the incentives are just to support the paddy farming industry in the current moment. There’s a whole lot of other stuff that needs to happen to sustain it for the future.

Malaysia is making serious strides to bring farming into the modern age

Food security is one thing, but the government’s efforts have to go beyond just boosting numbers and yields. We’ve already covered the financial side of Belanjawan 2025’s initiatives, but that’s just the tip of riceberg of the government’s plans.

Another part of this plan involves changing the perception of agriculture.

For years, farming has been seen as a tough, outdated, and underappreciated profession. But it’s evolving to show dem young kids that it’s not only modern now, but also profitable and – heck, even cool! And hopefully, that addresses the persistent problem we’ve been having with an aging workforce.

Gone are the days of farming revolving around cangkuls, buffalos, and sweating buckets under the hot sun 😮💨. These days, the government is getting farmers to embrace some cool tech to take farming into the future.

You may have heard of drones being used to spread fertilizers and pesticides, but they’re also used for precise ploughing and planting. There are things like motorized transplanters that get seeds in the ground quicker and more evenly, and combine harvesters that handle the entire harvest (i.e. cutting, threshing, and cleaning rice) all in one go.

For farmers still sticking to the traditional ways, there’s training and support to help them get on board with these modern methods.

And to really kick things into high gear, there are some hefty projects underway. One of them is the Five-Season Two-Year Paddy Planting Project in the Muda Agricultural Development Authority (MADA) areas. It’s a massive undertaking with nearly RM1 billion in funding covering 11,000 hectares. The aim is to increase paddy yields by 15% through strategies like optimizing irrigation, introducing high-yield paddy varieties, and improving farm practices.

They’ve also zeroed in on Sekinchan, Selangor, which has been recognized for its excellent paddy management, yielding harvests of up to 12 tonnes per hectare. To build on this success, they’re rolling out a pilot project to supply fertilizers (including organic ones) tailored to different paddy-growing areas.

It might sound like a lot of action happening all at once, but all of this is part of a bigger plan…

The big goal is to hit self-sufficiency by 2030

Last year it was announced that Malaysia was aiming to hit a 75% SSL by 2025, and 80% by 2030. For the time being, Malaysia will continue to rely rice imports.

But the strides being made in the industry are significant. Slowly but surely, we’re heading closer to self-sufficiency if we continue on the current trajectory.

And when that day finally comes, every bite of nasi lemak will taste so much better knowing it’s 100% ours.

- 3.6KShares

- Facebook3.3K

- Twitter40

- LinkedIn20

- Email53

- WhatsApp163