Gomen says inflation is low. So how come everything is so expensive?!

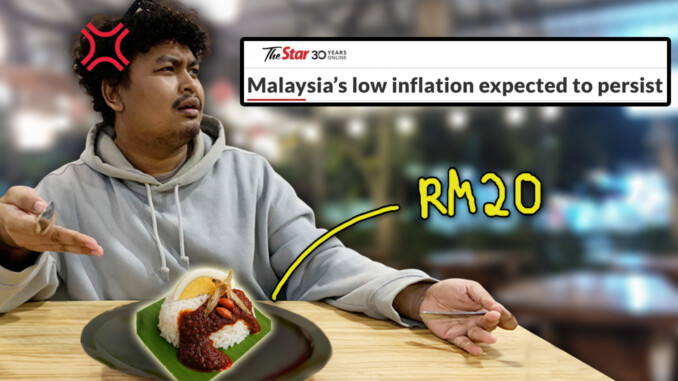

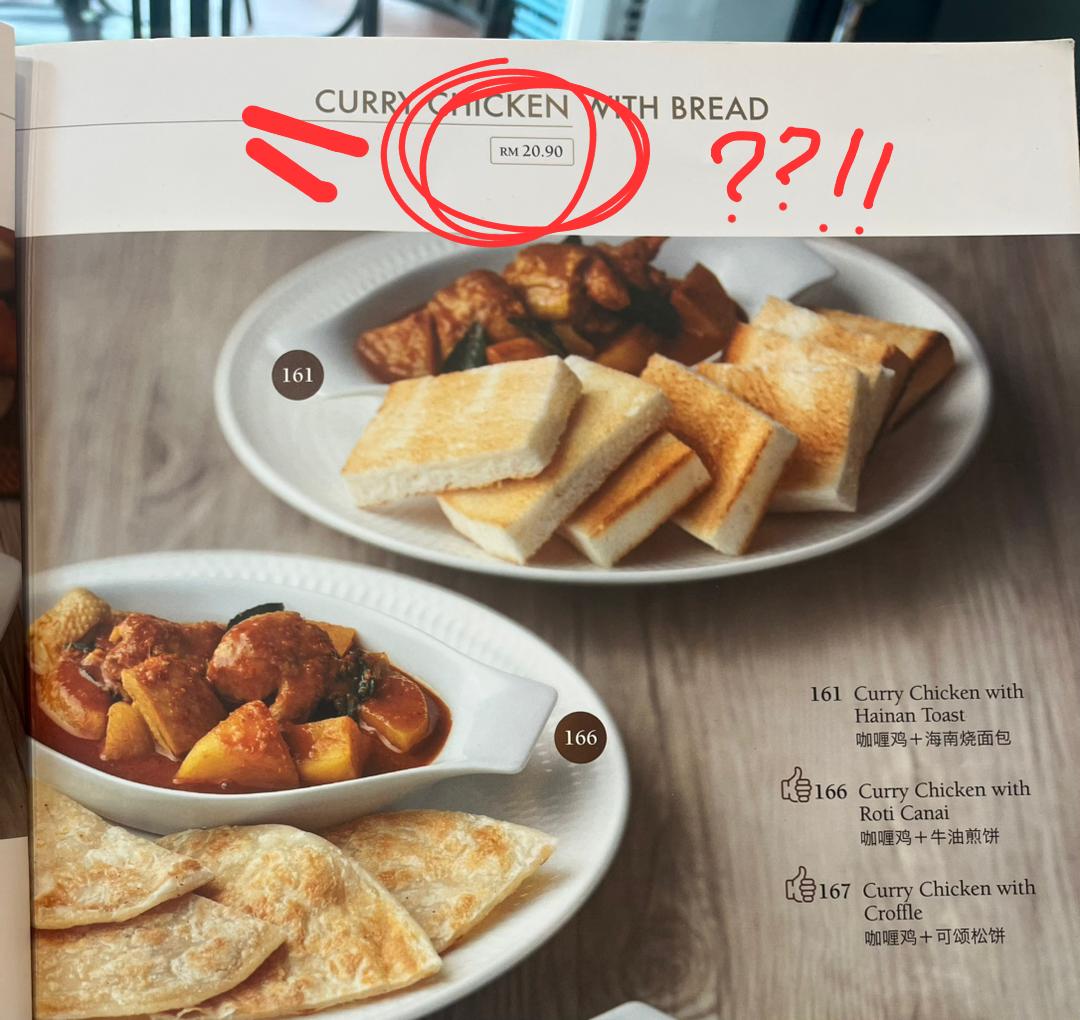

Just the other weekend, this writer joined some friends for roti canai. But one look at the menu, and she immediately lost her appetite.

Before y’all say that this must be some atas kayangan cafe, this writer remembers a time where a cup of coffee here was RM4.50. Now, the price is almost double at RM7.50. Seriously, when did things start getting this pricey?

But if you’ve been reading the news, inflation in Malaysia is supposedly pretty low right now. That’s a strange thing to hear when our koyak wallets are clearly having a totally different experience.

So what’s actually going on?

Well for starters, inflation being low doesn’t automatically make things feel cheaper. On the contrary, prices are generally still going up for things like food, healthcare, and utilities; and you can expect that upward trend to continue. But surprise surprise, rising prices alone don’t explain why your everyday errands feel so heavy on the wallet.

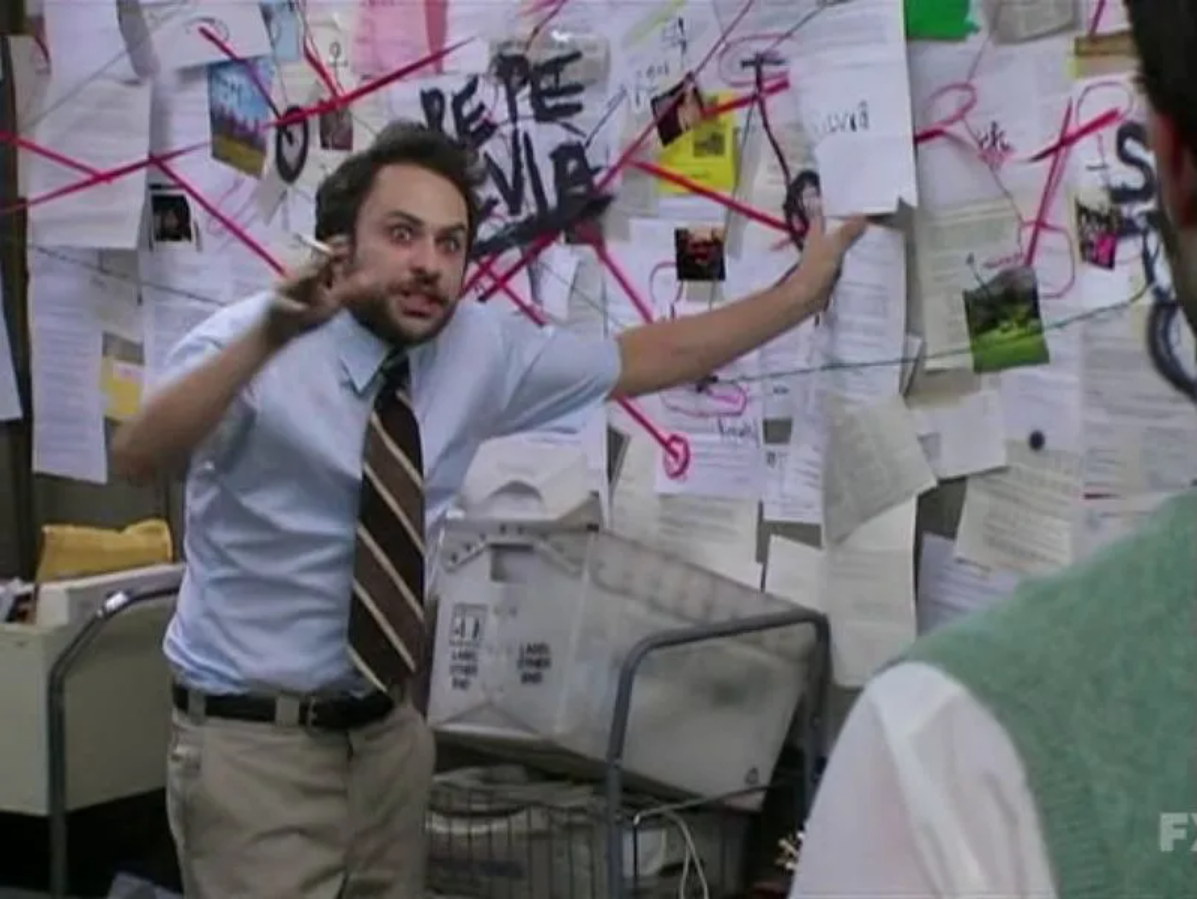

To really get what’s happening, we need to step back from the headlines and untangle a few things that often get lumped together, starting with the one thing everyone keeps quoting whenever life starts to feel expensive.

So… what does inflation actually mean?

At its simplest, inflation just means prices increasing over time. In Malaysia, inflation is measured using the Consumer Price Index (CPI). Think of CPI as a shopping basket filled with things the average household spends money on like food, housing, transport, healthcare, education and so on.

The Department of Statistics Malaysia (DOSM) tracks how much this basket costs over time. Then, Bank Negara Malaysia (BNM) uses those numbers to assess price stability, guide its monetary policy, and to keep inflation in check. So when inflation is reported at, say, 1.4%, it simply means that the same basket costs 1.4% more than it did a year ago.

And that’s it. That’s the whole definition.

So in short, low inflation doesn’t mean things suddenly become cheap again. It just means prices are rising more slowly. Think of it this way, if your kopi c used to cost RM4, then went up to RM6, a period of low inflation just means it stops ballooning to RM6.90. It doesn’t (and probably never will 😭) go back to RM 4.

While experts have been saying that inflation is easing, the cost of living – basically the total amount you need to maintain a basic standard of living – is still painfully high, especially when it comes to essentials. So if inflation isn’t the problem anymore, why does it feel like everything is still out of reach? And here’s where we tell you there’s actually a very human reason for that.

A big part of it comes down to how we actually experience prices in real life

In truth, we’re much more sensitive to price changes in things we buy all the time like groceries, petrol and utilities simply because those prices keep showing up in our daily routines. When something you pay for every few days gets more expensive, it’s almost impossible not to notice. It starts to feel like everything is going up, even if that’s not technically true.

Also, bad prices have a way of sticking in our heads. We remember the shock of rice or eggs suddenly getting more expensive, but we tend to forget when prices stay the same or even fall. So even when inflation is low, the memories of those price hikes are still there.

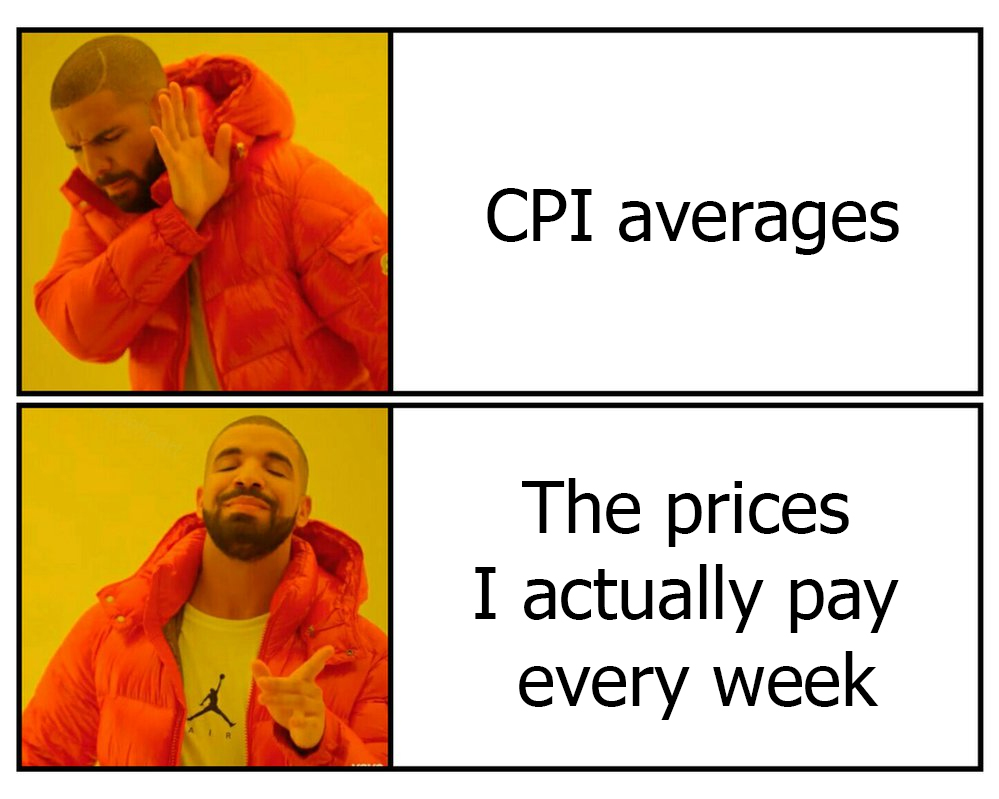

This is why official inflation numbers can feel weirdly disconnected from daily life. It smooths everything into one neat number, but our reality is shaped by what we buy most often, and which price jumps hurt the most.

And at this point, you might be thinking “So even if inflation dropped to zero, I’d still feel broke?” Oof. Fair question.

The thing is, so far we’ve only been talking about prices. And that’s exactly why looking at inflation alone doesn’t fully explain why so many people still feel tertekan.

The other half of this equation is Malaysia’s low wages

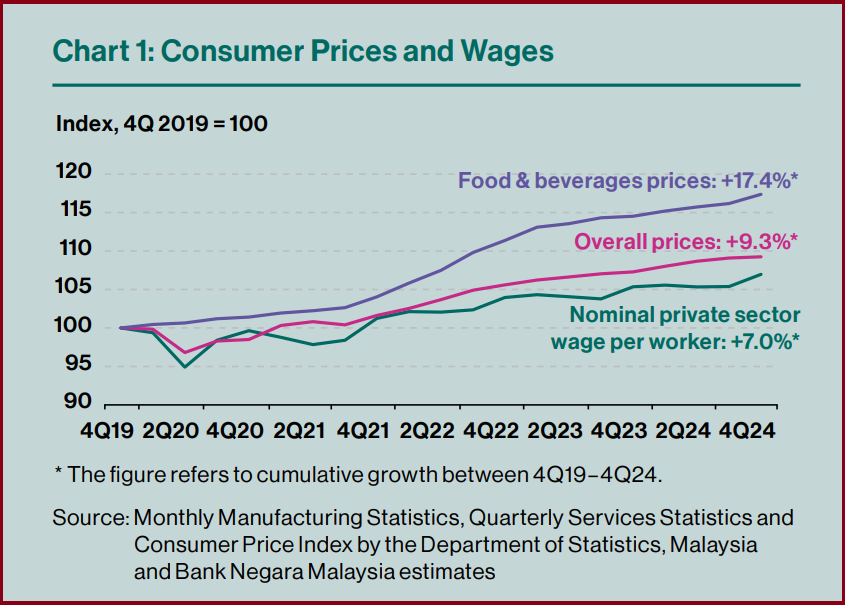

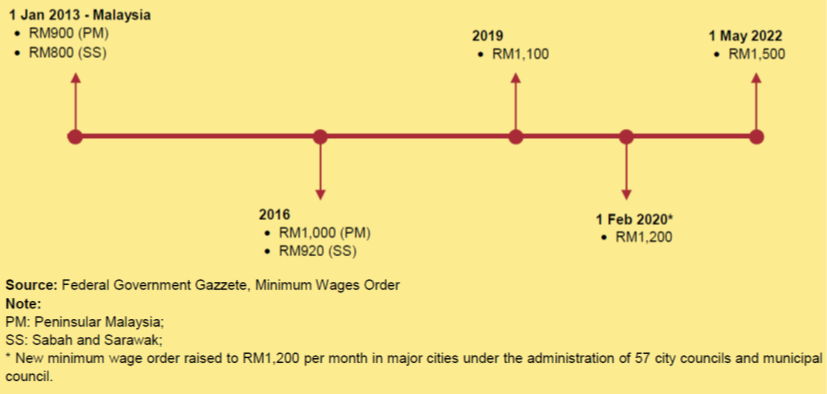

Even if prices stop rising quickly, life will still feel expensive if incomes don’t keep up. That’s just the cold hard truth. This is where purchasing power comes in, and why even people who are “comfortably” in the M40 bracket feel squeezed despite our current low inflation situation. Over the past few years, prices and wages simply haven’t been moving at the same speed.

Based on the chart below, salaries in the private sector are not growing as much as prices;

So yes, many Malaysians are earning more than before. But after accounting for higher prices, many are actually worse off.

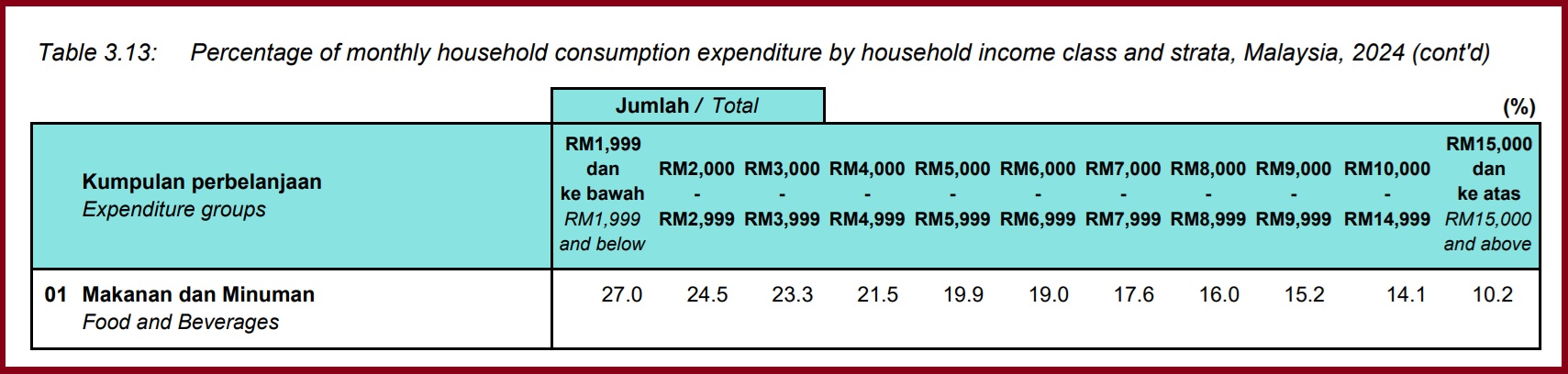

And this squeeze isn’t felt equally. According to DOSM, lower-income households spend a much larger share of their income on essentials like food- sometimes more than a third of what they earn- compared to higher-income households.

Naturally, the next question is…

Okay, so what’s in the works to help us cope with inflation & cost of living?

Yeah, put it all together and it kinda feels like some of us can’t even afford to breathe, let alone eat. 🤧😞 The slightly less terrible news is that policymakers are doing stuff… but their toolkit doesn’t allow them to do magic.

One of the biggest levers in that toolkit is the Overnight Policy Rate (OPR). It’s essentially the structural mechanism used to keep prices stable. By tweaking the OPR, the system influences how much people borrow, spend and save, which helps put a lid on inflation. Then when you factor in wages and supply issues, the goal is basically a massive balancing act of preventing prices from roller-coastering while making sure the economy keeps moving forward.

But BNM (who is in charge of setting Malaysia’s OPR) has also been very open about what monetary policy cannot do. For one, it can’t instantly lower prices. It also can’t 100% fix supply-side problems like global food costs or energy shocks. And it definitely can’t raise wages at the snap of a finger. That’s why inflation control is usually paired with other measures.

On top of that, national policies are leaning more into targeted help, from direct cash aid like Sumbangan Tunai Rahmah and Sumbangan Asas Rahmah, to more focused subsidies for fuel and daily essentials. It’s a more direct way of easing pressure on households that are feeling it the most.

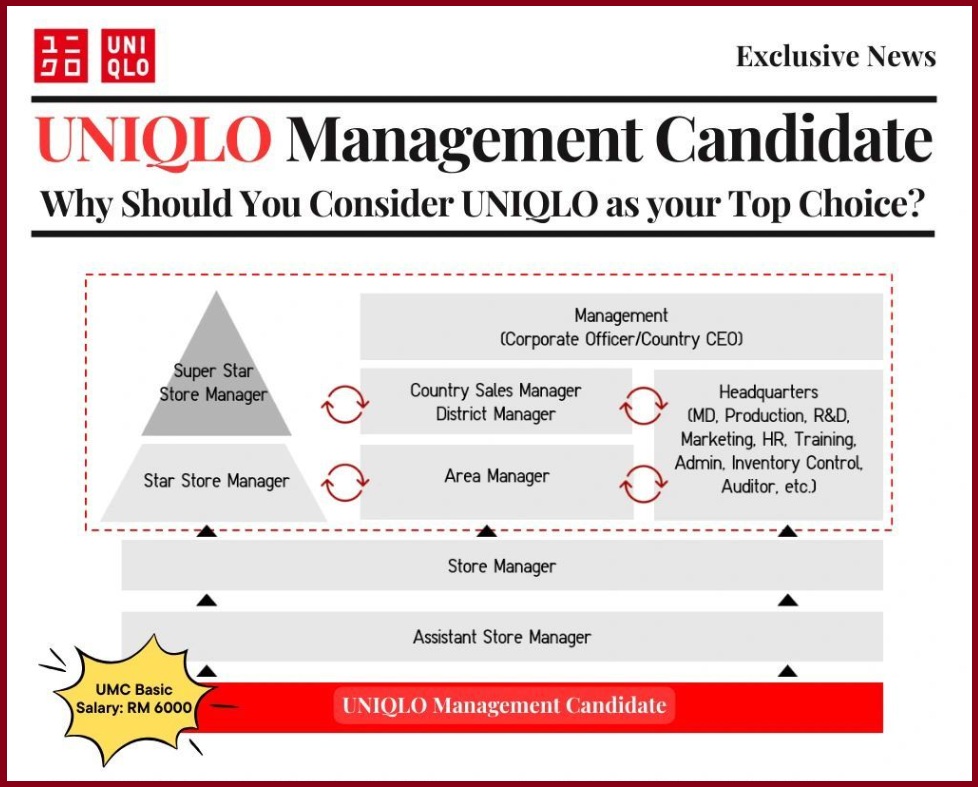

Beyond short term relief, the longer game is boosting productivity and attracting higher-value investments to lift wages over time. Hence why you’re seeing so much investment in AI, data centres, and even upskilling through TVET programs.

There’s also more talk about the idea of a living wage, which is basically how much someone actually needs to earn to live a decent life. That includes basics like food, housing, transport and healthcare, but also things like menabung and even socialising. The Belanjawanku Expenditure Guide released by EPF puts the living wage for a single person in 2025 at around RM3,100.

It’s not legally enforced like the minimum wage, but some GLCs and GLICs have started adopting living wages anyway, setting the tone for other employers.

At the same time, you might’ve heard that civil servants salaries were also raised by 13%+ this year, and that’s probably not a coincidence. The idea is that when the public sector starts paying more, private companies will eventually have to follow suit to stay competitive and attract workers, helping lift overall wages in Malaysia.

The thing about these solutions though is that they take time. Which brings us to the part everyone finds the hardest to accept.

Relief can feel slow, but there’s stuff we can do until it kicks in

The way we see it, prices, wages and policies are all moving on different timelines. Prices tend to move first, sometimes even overnight. But policy stuff like tax shifts, subsidy changes and wages can take years before they start making a difference in our daily lives.

Which brings us to the practical question: while we’re waiting for the bigger pieces to fall into place, what can we actually do in the meantime?

Honestly, the first step is just knowing what you’re dealing with.

Once you understand the difference between inflation, CPI, and cost of living, a lot of the noise starts to make more sense. It doesn’t necessarily make things cheaper, but it does help set expectations.

From there, it’s less about big economic fixes and more about the small, everyday choices. Even just loosely tracking your spending can help you spot leaks you didn’t realise were there. That could mean switching to ToU electricity if it helps lower your bills, taking public transport more often to save on tolls and parking, tapau-ing instead of relying too much on food delivery (which quietly bumps up prices), or doing things like bulk buying and meal prepping if it fits your routine.

There’s also the income side of the equation. So where possible, this might mean upskilling, taking on side work, or looking for better paying opportunities, especially when stagnant wages are what make inflation hurt the most.

None of this fixes the cost-of-living problem at its root, but it does give households a bit more control while the bigger, slower policy changes do their thing.