Kampung Baru Cinas are getting a makeover. This is their history

- 1.5KShares

- Facebook1.3K

- Twitter14

- LinkedIn14

- Email33

- WhatsApp65

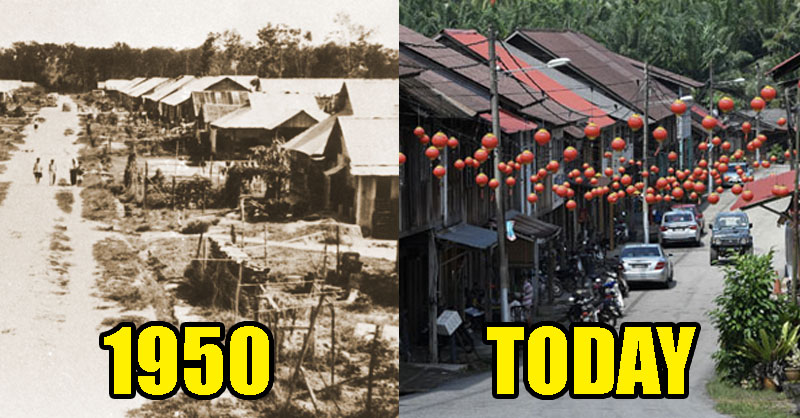

Recently, the government announced that they’ll be allocating RM104 million under Belanjawan 2023 to develop and upgrade Kampung Baru Cinas in Semenanjung Malaysia. They’re also planning to turn these historical spots into tourist attractions to help boost the local economy in the process.

But have y’all ever wondered how these Kampung Baru Cinas came about?

As the name implies, they’re basically residential areas which are mostly, if not entirely, populated by Chinese people. But unlike the name, they aren’t exactly baru. Houses in these villages tend to look haphazardly built, with many of them being old and wooden. On top of that, the roads that snake between the dwellings are often narrow and uneven.

That’s because these Kampung Baru Cinas weren’t townships planned out by a property developer. Unlike Chinatown, it’s not even a place where a bunch of Chinese people decided “Hey, I’m going to live here”.

In fact, moving to a Kampung Baru Cina wasn’t a choice at all.

Kampung Baru Cinas were created as a way to fight Communists

So, the origin story of Kampung Baru Cinas all boils down to the Malayan Emergency. Long story short, when the British came back to take control of Malaya in 1945 after the Japanese Occupation, they didn’t get the Malayan welcome party they were expecting. Instead, they got the Malayan Communist Party (MCP).

In the following 3 years, tensions were brewing between the Communists and the British with MCP-organized worker protests; where one successful protest in 1946 became a total of 300 worker strikes by the end of 1947. The British responded with increasingly harsher actions from arrests, to deportations, and the use of force that led to some workers losing their lives. And of course, the Communists retaliated by assassinating strikebreakers and attacking anti-union estates.

Everything came to a boil in 1948, when 3 Chinese men suspected to be Communists killed 3 European plantation managers near the town of Sungai Siput.

The British used the Sungai Siput incident and other plantation attacks as justification to declare a state of emergency (Darurat). But it wasn’t enough. Many Chinese moved to the outskirts during the Japanese Occupation, and many were now being recruited or forced to supply the MCP with essentials or information.

In 1950, the Director of Operations of the Emergency, Sir Harold Briggs, named a plan after himself. The Briggs Plan was to essentially consolidate these people in the outskirts into New Villages where they would have 24/7 security, new housing, and be safe from the Communists.

In reality though, it was just a marketing term for what was – for all intents and purposes – an internment camp.

Chinese and Orang Asli were forcibly relocated into New Villages

Unfortunately, an internment camp has nothing to do with interns. Rather, they are prisons for civilians with suspected links to the enemy. It wasn’t a novel idea either – the US government stuck more than 120,000 Japanese Americans into internment camps during World War 2.

In total, some 500,000 civilians were forcefully relocated in short notice, with many not having the time to fully pack their belongings. Whatever was left behind was torched to deny the Communists of supplies. It isn’t commonly known, but the Chinese weren’t the only targets for relocation. The British also forcibly removed Orang Asli from the forests to minimize their contact with Communists, but had to eventually abandon the plan when many of them died.

“…substantial numbers of Malayan aborigines were also moved to New Villages. Unaccustomed to a sedentary lifestyle and confinement to enclosed, insalubrious places, the death toll among them was larger…” – John D. Leary, Violence and the Dream People, quoted by A Miroiu via OSF.

In order to squeeze the fight out of the communists, multiple measures were put in place, such as:

- All citizens were required to register with the government

- Barbed wire perimeter fences

- Strict rations of staple foods, medicines and materials

- Heavy enforcement and spot checks

- Up to 22-hour curfews

These measures took a toll on the new villagers as much as the Communists. The rushed nature of the Briggs Plan meant that amenities like electricity, piped water and medical services weren’t available in many settlements, with local historian Gary Lit saying that many residents were lucky to even have kerosene lamps. Enforcement was also harsh, with reports of villagers being shot for going to the loo (jambans/outhouses) during curfew hours. As one elderly man recounted:

“…I thought we could be protected by the government and kept safe from the Communists… I never thought life behind barbed wire could be like that… Like a concentration camp, lah!” – quoted from Life Behind Barbed Wire: New Villages, Malaysia; via Medium

Whether or not the Briggs Plan worked is a matter of debate but, over the years, amenities were added, security was lightened, and barbed-wire walls went down. Despite the circumstances that led to them being there, many settlers eventually regarded the New Chinese Villages as….. home.

Nowadays, Kampung Baru Cinas are pretty nice places to live in

According to one of our writers who grew up in a New Village (Kampung Baru Ampang), they are pleasant places to live, with a strong sense of camaraderie within the community. Chances are, you’ll know your neighbors well, and be able to count on them to help you out. New Villages also tend to be quiet, cuz they’re fairly removed from the usual heavy traffic. Narrow roads, remember?

On the other hand, the same narrow roads can be an issue – there’s always the worry that you’ll run into an opposing car when you’re driving on a one-lane road. And while there are sundry shops nearby for your bare necessities, you might have to drive a distance to get access to basic public amenities like clinics or supermarkets. While some people like the quaint exterior of a bygone time, many Kampung Baru Cinas can definitely use an upgrade.

That’s why, in Belanjawan 2023, the government is allocating RM104 million to upgrade and maintain Kampung Baru Cina. This includes over RM67 million to upgrade the infrastructure, and RM5 million for house repairs.

And seeing as to how the vintage look of Kampung Baru Cinas often attracts local filmmakers, there’s no denying that they have the potential to become local attractions. Scenic kampungs such as Sekinchan, for instance, have bloomed into weekend getaway destinations for city dwellers.

Consequently, the government is also exploring the possibility of turning Kampung Baru Cinas into tourist spots to help boost the local economy.

Not just that, they are also allocating RM10.5 million to provide business loans of up to RM50,000 for Kampung Baru Cina residents who are planning to expand their business.

And since the Belanjawan benefits a wide range of people – some initiatives are aimed at entire communities, and some are there for individuals – you’ll most likely find an initiative that benefits you. If y’all are interested, check out the Manfaat Belanjawan 2023 portal.

- 1.5KShares

- Facebook1.3K

- Twitter14

- LinkedIn14

- Email33

- WhatsApp65