The tragic tale of Papan, perhaps the unluckiest town in Perak

- 1.3KShares

- Facebook1.2K

- Twitter11

- LinkedIn13

- Email18

- WhatsApp63

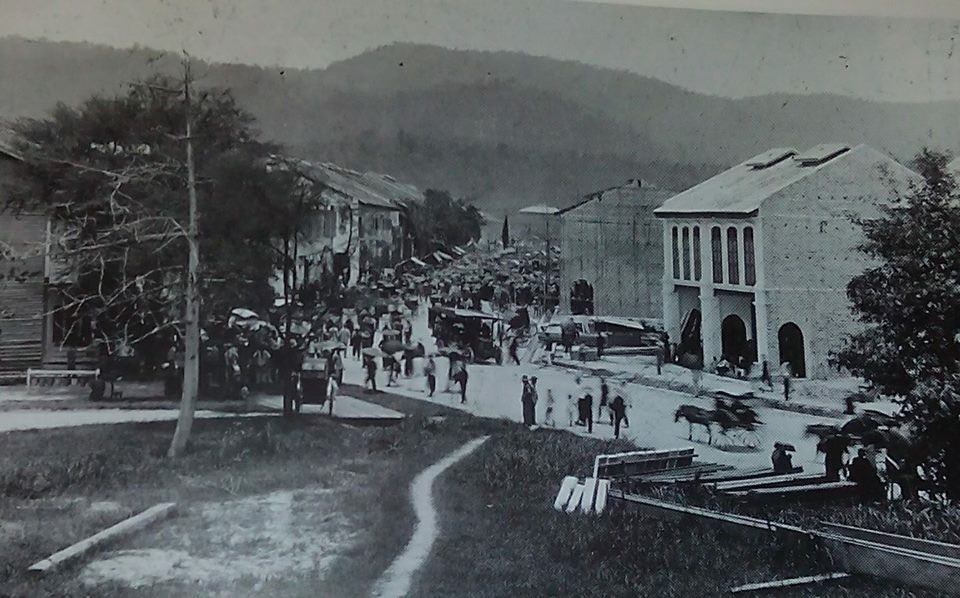

The tin mining industry had been an important part of our colonial history, being among the earliest forms of mining present on the Malay Peninsula as early as the 1820s. By the turn of the 20th century, the Malay colonies became quite rich in tin.

Although the mines had mostly gone silent today, former mining towns like Ipoh and Larut in Perak still stand tall despite being relegated to tourist attractions. But the same can’t be said for a certain town off the beaten path:

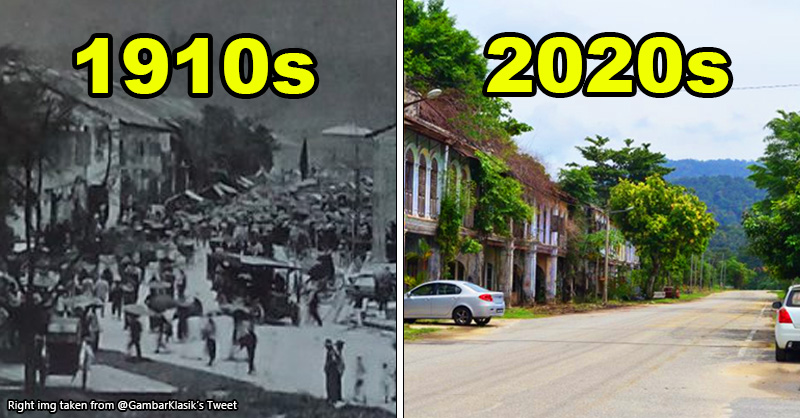

This is Papan, a (nearly) deserted town that, on first impressions may not seem remarkable to most people. Old shophouses line the only main street, with many left to crumble as years passed and overgrown with vegetation. If one were to squint, it’d look like something out of I am Legend.

It would be understandable if this and the ironically deafening silence when strolling around did not impress at all. But under all the trees and weathered concrete is two centuries’ worth of history left to rot, quite literally.

And interestingly, this old husk did not start with tin…

Before tin, Papan made… well, papan

Surprisingly, little is known about the town’s beginnings. But from what we know, it was originally an old lumber town populated by both Malay and Chinese workers since the 1840s, hence the name Papan, Malay for ‘plank’. The export of the day? Some hardy Chengal, used for boats, buildings and fancy furniture.

Down the line, Chinese miners came in and started mining tin, though operations weren’t as expansive as in later years. And all that wood that Papan was harvesting? It helped provide material for equipment for the early mines, as well as fuel for later steam-powered machinery.

In 1875, the British took Papan and handed the town over to Mandailing Chief Raja Asal as thanks for his efforts in the Perak War. It was thanks to Raja Asal, and later his successor Raja Bilah that Papan’s tin mines were expanded just in time for a tin rush in the 1880s which made Papan immensely wealthy with some help from local Chinese magnates.

It was here that Papan entered its heyday, growing into a rich mining hub, like an Ipoh 2.0. It was a pretty chill place to live in apart from a small secret society hiccup:

“On 29 November 1887, a brothel skirmish escalated into a secret society riot. A violent clash took place at Papan… There were 9,000 of them on one side and 8,000 on the other.” – Excerpt from ‘Raja Bilah and the Mandailings in Perak: 1875-1911’

Okay, maybe small is an understatement considering the fact that thousands almost cut each other down, yikes.

But it wasn’t the only big mishap in Papan, as World War II came…

Insurgents nearly ground Papan’s industry to a halt

For context, when Japan invaded Malaya, the Malayan Communist Party (MCP) established the Malayan Anti-Japanese Army (MPAJA), which went underground soon after the British surrendered in 1942.

And in Perak, Papan became a hotspot for MPAJA activity, notably a detachment of the MPAJA, the 5th Independent Regiment that was messing around in the forests surrounding the town. Though we can’t find specifics regarding insurgent activity in Papan, we know that they at least had some help from Sybil Kathigasu, a nurse-turned-freedom fighter who made her mark in history by aiding the MPAJA.

Tin mining in Papan took a backseat at this point in time, with operations being scaled back immensely or completely stopped outright, and the brutality of the Japanese occupation probably didn’t help much either. After World War II ended, mining resumed at Papan, but the continuing insurgency made things rather miserable until the end of the Malayan Emergency in 1960, when the forests around Papan were declared safe once more.

Regardless of these headaches, Papan seemed to be doing pretty well until…

Papan’s tin industry crumpled like a soft drink can

By the 1970s, mining operations had slowed down to a figurative crawl. Not ideal for a mining town, but it was still relatively lively even after the Malayan Emergency threw Papan in for a wild ride. Even so, Papan was not as wealthy as it used to be, owing to said chaos and slow recovery of the industry post-war.

But in 1977, a local mining company attempted to revive Papan’s tin-mining industry after a new deposit was found under the town itself. 60 households were shuffled over to nearby Kampung Papan Baru and plans were made to relocate the rest of the town in order to clear the area for new operations. It looked like things were on track for Papan once more.

Unfortunately for the town, tin prices took a headlong dive.

For context, there was an international treaty of sorts to keep tin prices stable: the International Tin Agreement (ITA). A governing body, the International Tin Council (ITC) was supposed to pump cash in to maintain it. But the ITC ran out of money, triggering the collapse of the ITA in 1985, causing tin prices to plummet and crippling Papan’s future for good.

Soon, what few miners left in town migrated, abandoning it to its fate. Running concurrently, however…

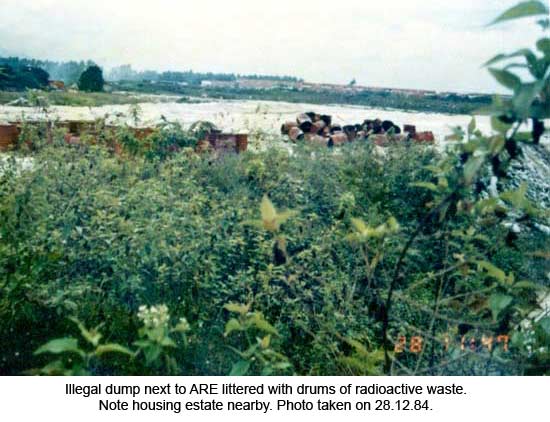

Radioactive waste drove many more away

If you read our article on the whole Asia Rare Earth (ARE) scandal, good on you, but for those who didn’t, ARE had built a radioactive waste disposal site near Papan in 1984, which worried residents greatly. And when complaints went unanswered, residents from Papan and nearby towns banded together, starting the first of a series of protests against ARE.

Soon, Papan’s residents took ARE to court, with both sides trading blows frequently in multiple court cases. They’ve even brought in scientists to help with checking if the disposal site is safe over the course of 8 years. Safe to say, both sides didn’t hold back at all, and Papan eventually came out on top in 1992, but at far too great a cost.

Among the terrible consequences of the ARE crisis were the side-effects of the radiation. There were several cases of children born with defects and disabilities, alongside cases of leukemia that occurred in the area. The fears of irradiation, alongside the failing tin industry, quickened Papan’s demise. By the end of the ARE crisis in 1992, Papan was left almost completely desolate, and its mines falling silent one last time.

As a visitor of a nearly-deserted Papan today, knowing its history, one can’t help but think that…

Papan’s history is just a series of unfortunate events

Papan as it stands today is not as desolate as one expects: few homes around town are still occupied, albeit by an aging community. But for any who walk past its crumbling buildings, the thought that a town this important was left dilapidated unnerves even the least passionate amateur historian.

In a way, Papan shares much of its history with its northern neighbor, Ipoh. Both had grown out of the tin rush of the late 1800s; both had suffered the Japanese onslaught and insurgencies during the mid-20th century; and both had suffered from the decline of the tin industry in the 1980s. Yet Ipoh endured and evolved into a tourist icon, while Papan lays mostly forgotten.

With all that in mind, it is easy to understand the importance of local authorities acknowledging Papan’s industrious past, and it seems like they actually considered restoring the town in 2019, but nothing had come of it. Perhaps it is better that way, for some may say the town’s charm comes from the state of disrepair the town was left in, which some described as ‘A town lost in time‘.

Despite all that Papan had suffered, one can’t help but contemplate whether the town could have averted its fate, and endured like its neighbors did instead.

- 1.3KShares

- Facebook1.2K

- Twitter11

- LinkedIn13

- Email18

- WhatsApp63