Giving condensed milk to babies was trendy in 1900s Malaya. This lady fought to change that.

- 1.5KShares

- Facebook1.4K

- Twitter7

- LinkedIn6

- Email12

- WhatsApp52

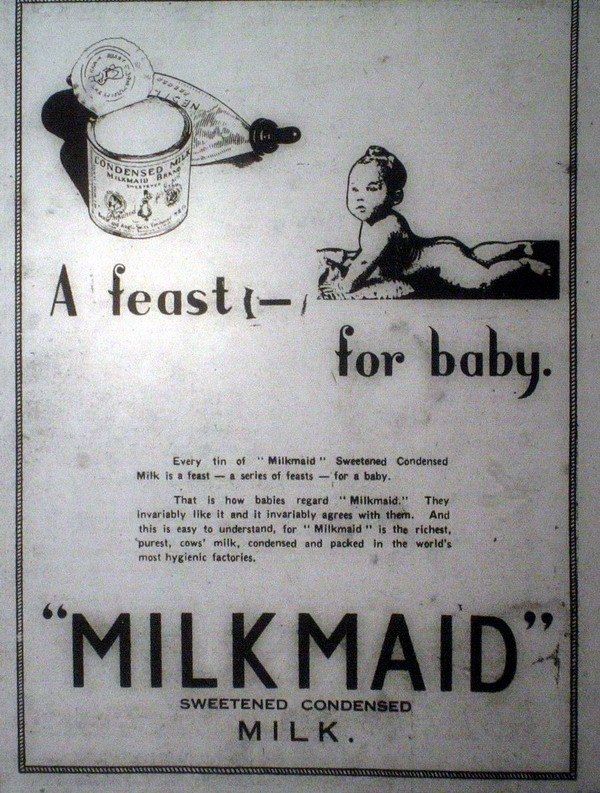

Here’s an interesting experiment. Go to your pantry or a grocery store, and find a can of milk. Condensed, evaporated, creamer – it doesn’t matter. Chances are, you’ll find a tiny warning on the label that says that the milk in this can is not suitable for infants/children below 12 months, or something along those lines.

Huh. Since when have those warnings been there? Well, we’re guessing since 1985, since that’s the date of the regulations that put them there. And if you read through the regulations…

“There shall be written in the label on a package containing condensed milk or sweetened condensed milk the words, “condensed milk” or “sweetened condensed milk”, as the case may be, immediately followed by the words “NOT SUITABLE FOR INFANTS”. The words shall form the first line or lines of the label and no other words shall appear in the same line or lines…” – R95 of our Food Regulations 1985.

…you would think that a baby was killed by condensed milk in the past or something. Well, maybe not a baby, but more like a truckload of babies. After some digging around, it turned out that probably thousands of babies had died from being fed condensed milk in Malaysia’s past. Because for a lot of Malayans back then…

Feeding your baby condensed milk was considered a trendy and atas in the late 1800s

So back in the late 1800s, drinking fresh milk showed that you’re atas, but with more British people and laborers coming into Malaya, the local cows just can’t make enough milk for everyone. That’s when canned milk entered the chat. Unlike fresh milk which came from mostly Indian farms in colonial Malaya, canned milk is convenient, lasts a lot longer even without a fridge, is ‘cleaner’, and back then, marketed as nutritious enough for growing babies.

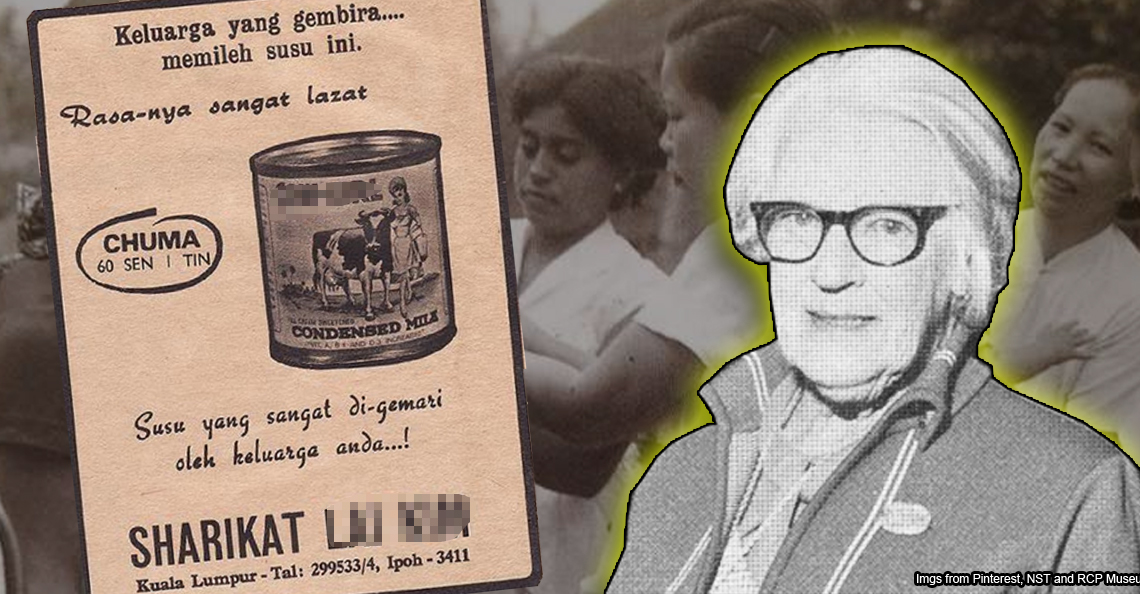

All these things about canned milk made it really popular among British mothers, some of whom ‘regarded breast feeding as déclassé, if not downright animalistic’, and rich Chinese mothers, whose culture of wet nursing and breast binding practices didn’t lean towards breastfeeding in the first place. Coincidentally, these were the people who could afford canned milk at first, since they were a bit pricey back then. For example, in the early 1900s, these were the prices of three brands of canned milk:

- Milk Food, a product of Nestlé, costed $7.50 for a dozen = about 63¢ per tin

- Glaxo Milk, when first introduced, costed $15 per dozen = about $1.25 per tin

- Aurore Milk, supposedly the cheapest, costed $5.50 for a case of 48 tins = about 11¢ per tin

Considering that a typical amah in that time period earns only $25 per month, and that a standard Malayan family having five or six children typically had to live on $50 a month, feeding your baby canned milk had the bonus side effect of making you look really high class, especially since the angmoh ladies and rich Chinese aunties were doing it. Canned milk became really trendy, and soon the less-rich parts of the society followed suit ‘to appear more modern, looking to imitate the wealthier classes‘. In a way, canned milk became the new atas in Malaya.

With the introduction of less expensive (and naturally less nutritious) brands of canned milk, more people from all levels of society abandoned breast milk and fresh cow’s milk in favor of the new trend. In fact, it was noted that in rural Kelantan in the 1930s, some Malay mothers took pride in the extra expense from feeding their children canned milk, as opposed to the relatively free practice of breastfeeding. But not everyone embraced canned milk for the prestige.

Some working mothers switched to canned milk for the convenience. In Singapore, not having either nursery facilities at work or the time off to care of their babies (government service then only allowed for 2 to 6 weeks leave after confinement) forced mothers to choose between breastfeeding, a job, or feeding their kids canned milk. For poor families, canned milk, particularly the sweetened condensed kind, can really stretch the budget: besides being cheaper than fresh milk, the extra sweetness meant they can dilute it far more than recommended on the label to make it last longer.

Coupled with aggressive marketing by milk peddlers, canned milk made their way across Malaysia, with some noting that by 1930, condensed milk can be found in Terengganu, which used to be hive of Malaya’s fresh milk production. But long before that happened, the authorities have already worried about the prevalence of cheap, not-very-nutritious canned milk.

“One fears that a large amount of tinned milk of poor quality is sold in Kota Bharu. Such milk is not a nourishing food for children, but, being cheaper, is bought in preference to more nutritious brands. This matter has obviously an important bearing on infant mortality.” – Kelantan State Medical Department, from a 1917 report.

And they weren’t wrong. With practically everybody feeding their babies canned milk, infant mortality rates were worryingly high. So high that at its height…

In KL in 1921, for every 10 babies born, 7 died within their first year

To be more precise, according to an article written in May 1921, Kuala Lumpur reported an infant mortality rate of 760 per 1,000. In less statistical terms, it would mean that for every 1,000 babies born in KL at that time, 760 of them died within a year after being born. That’s a very worrying number, and it was reportedly “due to the ignorance of mothers in feeding babies and also unhealthy surroundings“.

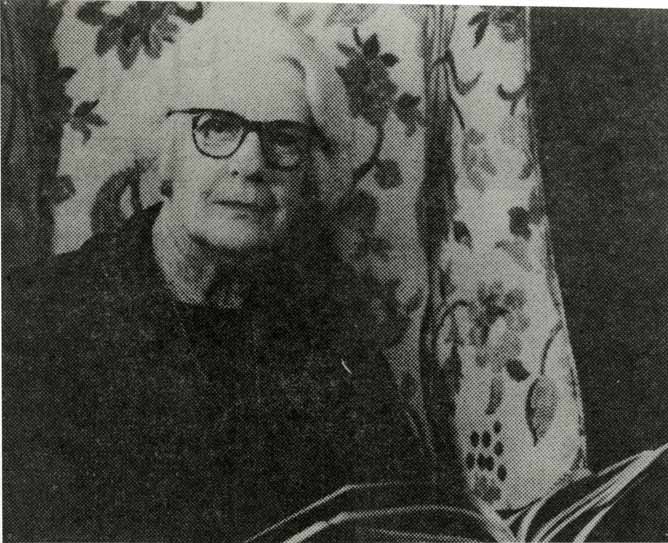

Thankfully, that number was freak incident, but the average infant mortality rate around the early 1900s wasn’t any less worrying: roughly 250 per 1,000 babies born. While some of the deaths can be blamed on other things and diseases, poor nutrition, particularly from feeding newborn babies with sweetened condensed milk, seemed to the prime suspect. At the very least, it was that way to Cicely Williams, a medical officer who was posted to Malaya in the late 1930s.

In case you dunno who that is, she practically discovered the kwashiorkor disease, so her words carry some weight. Her time in Malaya inspired one of her famous speeches, called ‘Milk and Murder‘. In it, she noted that while people from all levels of Malayan society fed their babies sweetened condensed milk, the higher classes were less affected, because of the extra care given to their babies.

“If the tuan besar‘s baby is given sweetened condensed milk, it is also given cod liver oil or some expensive preparation containing the vitamins A and D. It also gets bathed regularly; it gets plenty of fresh air and sunshine. It wears soft, fine clothes that are regularly washed. It lives in an atmosphere that is relatively free from infection and it grows fat and smiling.” – excerpt from ‘Milk and Murder‘, by Cecily Williams.

Whereas in the lower rungs of the society, poverty and certain circumstances didn’t give their babies much of a fighting chance. Poor mothers often had to work, leaving little time or energy to care for their babies, much less breastfeed them.

“…the baby is given sweetened condensed milk out of a dirty bottle. It is rarely or never taken out into the sunlight. It is hung up in a sarong and gets hot and sweaty. The baby gets fever and then is never washed. It develops boils and finally when they think it is going to die, the parents bring it into hospital to avoid funeral expenses…” – excerpt from ‘Milk and Murder‘, by Cecily Williams.

As put forth by Williams, part of the problem with sweetened condensed milk is that it’s very sweet. The high sugar content will eventually make babies more prone to boils, sores, and diarrhea. Because of its sweet taste as well, babies fed with condensed milk often get hooked on it, preferring the sweet stuff rather than breast milk. The other problem with condensed milk is that when severely diluted (as is the practice in poorer homes), they don’t have enough fat to carry vitamins like A and D. Vitamin A helps protect the eyes, while vitamin D protects the baby from rickets and convulsions.

As stated in the excerpt, these deficiencies weren’t a problem with rich people with their expensive cod oil, but what about the poorer people? Well, the government then had actually done something about it…

To stop kids from going blind, they were given… red palm oil

This is a side story, but it’s worth looking at. Apparently, it’s possible for children to get eye problems like night blindness and corneal ulcers by not getting enough vitamin A in their diet, and this condition is called keratomalacia. And it was a pretty big problem back in the day. According to a report, near the end of the 1930s, a staff in Singapore’s General Hospital examined 30 babies that were admitted due to keratomalacia. It was found that 28 of them were regularly fed with sweetened condensed milk.

All this time, the government had been distributing free canned milk to mothers who can neither breastfeed or afford milk. Once the link between condensed milk and keratomalacia was made clear, they ordered research on a kind of local food that could be distributed along with the canned milk as a vitamin A supplement. After a thorough analysis, it was found that the food having the most carotene (what Vitamin A was known as back then) that can be found locally was… red palm oil.

Red palm oil is a lot cheaper than imported cod oil, and like canned milk, it keeps for a long time. So bottles of palm oil were distributed through child welfare centers across Malaya. In Tamil plantations, where vitamin A deficiency diseases were most prevalent, children were given skimmed milk with red palm oil mixed in it, as well as a kind of cake made from soybeans, skimmed milk powder, dal and rice flour, fried in unrefined palm oil. The children reportedly gobbled these up, and their eye and skin disorders cleared up after a few months of the stuff.

Then WW2 and the Japanese came, and palm oil supplements took a weird turn. Even canned milk was hard to get because of the war, so building upon the previous administration’s work on red palm oil supplements, the Japanese tried to get Malayans to consume red palm oil through propaganda exalting the goodness of palm oil. In areas where they had the most control, they reportedly forced children in schools to drink a spoonful each day, Scott’s emulsion-style. If they refuse, they get da slapp from a teacher.

“Sometimes a sweet or peanut was given to assist with ingestion. Children would end up holding their noses while a teaspoon was shoved into their mouths, brimming with reddish oil.” – excerpt from “Milk for Everyone?” by G.K. Pakiam, (2020)

Besides the spoonful, children were also regularly issued with slices of cornbread slathered with red palm oil. As you can probably imagine, it was reported to taste greasy and horrible. Due to this aversion to red palm oil, some Malayans turned to other things to get their fat and vitamins, like coconut milk. Strangely enough, after the Japanese left in 1946, it was found that the infant mortality rate in Malaya dropped drastically, from being in the hundreds to only 92 per 1,000 babies.

It was later found that food and condensed milk shortages was among the reasons: mothers ate alternative foods that turned out to be healthier, and babies have to be breastfed. However, while infant mortality rates continued to decline after the war, mothers went back to bottle feeding their children, leading to a rash of health problems among babies like gastroenteritis, for example. So you might be wondering…

What happened to Dr Williams after her big speech?

It may seem unfortunate that Williams’ ‘Milk and Murder’ speech didn’t entirely stop canned milk from reaching newborn babies in Malaya, but after the speech, she continued to develop her concepts surrounding an integrated health service for mothers and children, and it resulted in an experimental primary health scheme in Terengganu. Remember how she recognized that canned milk was only part of a bigger problem for poorer mothers? Well, besides linking several village health centers together in a network, they were staffed with both nurses trained to recognize the social aspects of disease, as well as local midwives (bidans) who were trained to use safer methods.

Unfortunately, the Japanese invasion happened, and Williams trekked through the jungle all the way to Singapore. There, she was caught and made prisoner at Changi Prison by the Kempeitai, the Japanese’s secret police. Although not tortured like the male prisoners, she was kept in a tiny cage and was so malnourished that she lost a third of her body weight, and developed beri beri which left her with numbness in her feet until the end of her days.

Despite that, she continued her work of advocating proper nutrition in prison, by keeping records on the state of nutrition of all prisoners. She observed that despite the appalling conditions they were born into, breastfed babies managed to survive.

“Twenty babies born, 20 babies breastfed, 20 babies survived. You can’t do better than that.” – Cicely Williams, as quoted by the International Organization of Consumers Union.

The war ended with Williams physically bowed and having grey hair, but still with spirit. Her talents were recognized soon after the war, when she was made the first head of the Mother and Child Health (MCH) division of the World Health Organization (WHO), and after that their MCH head in southeast Asia. During that time, she managed to promote her vision of using local resources rather than first world of health care to improve the health of the poor. The remainder of her life was spent on research and teaching in several different countries across the globe, and basically being where she was needed.

In July 1992, Williams passed away in Oxford. While she may no longer be with us today, the short time she spent in Malaya probably influenced how we now see infant nutrition, and how we shouldn’t feed condensed milk to babies if we can help it.

- 1.5KShares

- Facebook1.4K

- Twitter7

- LinkedIn6

- Email12

- WhatsApp52