Always getting spam calls? Here’s how spammers buy your phone number

- 2.4KShares

- Facebook2.1K

- Twitter23

- LinkedIn13

- Email28

- WhatsApp163

At the end of every spam call asking if you wanna buy property, donate money, or take up a too-good-to-be-true part time job, you’re probably wondering, “How the heck did they get my number?”. But deep down inside, you know the truth. Oh, you know your number’s been leaked somewhere… the question is: where?

The good news is that it’s not just you. In April 2023, Malaysia hit the #1 spot on the list for most leaked and sold phone numbers in the world, where up to 73% of Malaysian mobile numbers were compromised.

So, together with our friends at Jabatan Perlindungan Data Peribadi (JPDP), the government agency in charge of personal data in Malaysia, we set out to find out:

- How much personal data really costs, and

- How they got leaked in the first place.

JPDP has their own answers, but we also asked someone from an industry that’s quite associated with spam calls – a property agent. We got quite a bit of a shock when he revealed that…

Your personal details are being sold for ONE Sen

You’d think that spammers and scammers are paying hundreds or thousands of Ringgit for your phone number, IC details, and addresses but…… nope. In fact, to these spam callers, you’re just another number worth 1 sen:

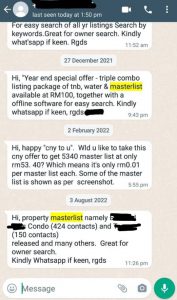

Mike (not his real name) told us that he’s received WhatsApp messages from data brokers selling what’s known as “masterlists” – basically lists of hundreds upon thousands of names, phone numbers and possibly MyKad numbers and addresses of residents in:

- a given geographic area (like Old Klang Road or Kelana Jaya), or

- a residential development (like a condo)

Mike was willing to show us these messages because he considers himself one of the “good guy” property agents. He doesn’t layan these messages, but says that more… “enterprising” property agents could buy the masterlists and use it for marketing purposes.

But here’s the thing – if you do the math, they’re selling these masterlists for about RM50 for 5,000 contacts. Obviously, getting only RM50 for one sale doesn’t make good business sense, so imagine how many people they’re selling the masterlist to, and how many people are buying it. If you ever wondered why 20 different marketers are calling you, there’s your answer.

But that leaves us the question:

How did they get your data in the first place?

We spoke to Puan Uma Annamallai, Director of Policy & Strategic Planning for JPDP, and she says that there are multiple ways your information can be leaked out, but they generally fall under three broad categories:

- An insider in the company leaks the data out

- The company fails to implement proper SOPs

- External attacks by hackers

An insider leak is the one we most commonly see on TV – the disgruntled or greedy employee or someone who’s recently been fired and seeking revenge. More often that not though, it’s mainly for the money.

“Some person who has access to the data saves it, and they have connections to those with wrong intentions or commercial criminals. Then, they sell the data to these criminals.” – Puan Uma, in an interview with CILISOS

However, it takes two hands to steal, so these insiders are usually enabled because companies often fail to implement proper SOPs when it comes to data security.

Sometimes the cause of the leak doesn’t have to be malicious… it can also be accidental, like when a health center in the US caused the health info of 100,000 patients to be leaked when they didn’t properly dispose of their hard drives. To prevent this, some companies have SOPs tighter than the cap on a cold bottle of cilisos; such as banning workers with access to personal data or servers from bringing recording devices (smartphones, USB sticks, external hard disks) to wherever the data is stored.

“Every organization is required to train their employees in line with the Personal Data Protection Act 2010… because the lack of training is one of the main reasons breaches happen.” – Puan Uma, in an interview with CILISOS

Last but not least, if a company’s cybersecurity isn’t up to snuff, malicious hackers can huff, puff, and blow the firewalls down. While it’s not as common as the previous two, Puan Uma says data breaches due to hackers aren’t unheard of. Nobody’s really 100% safe, not even the ex-Malaysian Prime Minister – his Telegram account was hacked a couple of months ago.

And generally, all that stolen or leaked data will end up in the hands of data brokers, like the person who WhatApp’d Mike. These people act as middlemen for data, selling it to scammers, telemarketers, criminal syndicates, or on the dark web where it can be further misused.

Malaysia has a law to protect your data, but it isn’t perfect (yet)

The Personal Data Protection Act (PDPA) 2010 is supposed to protect the personal data of Malaysians in business transactions and e-commerce from misuse. Any company or individual can be hit with a fine of up to RM500,000, jail time of up to 3 years or both if they mess up:

“…the penalty under the PDPA is very severe, and anyone, from the top of the company to the bottom, can be prosecuted.” – Puan Uma, in an interview with CILISOS

But the problem is that the PDPA isn’t perfect. In fact, it’s not only a problem in Malaysia because cyber laws are noted to be at least 5 years behind current technological developments and likely that gap is even larger today. The PDPA was introduced in 2010, and it has yet to catch up with some aspects of technology developed in the past 12 years or so.

Puan Uma told us that there are plans by the JPDP to patch up the PDPA to address some of these issues, the first of which is requiring companies to appoint Data Protection Officers.

Data Protection Officers are basically people who are specially trained to make sure a company is complying with the PDPA and report data breaches to the JPDP’s Data Protection Commissioner. Puan Uma added that it’s a move that’s been made by countries like Singapore to apparent success, and we’re following suit.

But what if the company outsources the data to a different company? According to Puan Uma, it’s quite common for companies these days to engage with these third parties, who are known as data processors.

Here’s an example of how it works: An online shopping platform, Beli Besar Sdn Bhd, might hire Data Cekap Sdn Bhd, a company that specializes in data processing, to handle their data. In this case, Data Cekap would be the data processor for Beli Besar. The PDPA right now doesn’t really cover data processors, and the JPDP aims to fix that with amendments to the law.

Lastly, JPDP wants to make breach notifications mandatory under the PDPA. As it is now, it is common practice for companies to inform JPDP whenever a data breach happens, but companies are not required to do it under the PDPA. So yeah, addressing this would help companies be more accountable when a leak happens, and JPDP can then start investigations wherever necessary. JPDP actually has more amendments in store, but for now, these are the three main ones they wanna highlight.

What if you find out your data’s been leaked, tho?

Give JPDP a call if you know your data kena bocor in commercial transactions

Sometimes, you don’t even need to get hacked or have your data stolen by a wayward employee – you might be giving it away by just… not reading forms properly. We’re willing to bet that none of y’all read the fine print whenever you click “I Agree” on websites and apps, or when filling in forms. A lot of the time, these permissions include giving your permission for your data to be used for tracking or marketing purposes.

Puan Uma also advises everyone to be more careful when putting up your personal information on social media platforms:

“Many people put their phone numbers and addresses on their social media profiles, and that can potentially end up in the wrong hands.” – Puan Uma, in an interview with CILISOS

It’s never pleasant to know that our data’s out there being bought and sold like cars in a secondhand dealership. Even so, there are things you can do about it, the first of which would be to make a complaint to JPDP either:

- Through this online form

- By calling them at 03-8911 7927

- Via email at [email protected]

- Or going in person to their office in Putrajaya

Once you do, JPDP will launch an investigation, and if the offending company is found to be sus, JPDP will take them to court (like this case which was eventually settled out of court). You could also just try to sue the company yourself, but PDPA being criminal law means it doesn’t work for civil lawsuits.

Also also, we previously did an article on how to stop getting spam calls, so if you’re being bombarded by spammers, that might help y’all out.

This article was originally published on December 20, 2022; with updates in April 2023

- 2.4KShares

- Facebook2.1K

- Twitter23

- LinkedIn13

- Email28

- WhatsApp163