4 of the coolest discoveries by the late Dr Lim Boo Liat, Malaysia’s pioneering zoologist

- 2.5KShares

- Facebook2.4K

- Twitter11

- LinkedIn16

- Email20

- WhatsApp40

[This article was originally published in July 2020.]

It’s not often that zoologists make news headlines in Malaysia, but the most recent headline was a sad one. Dr Lim Boo Liat, one of the main pioneers of zoology in Malaysia, had recently passed away at the ripe old age of 94.

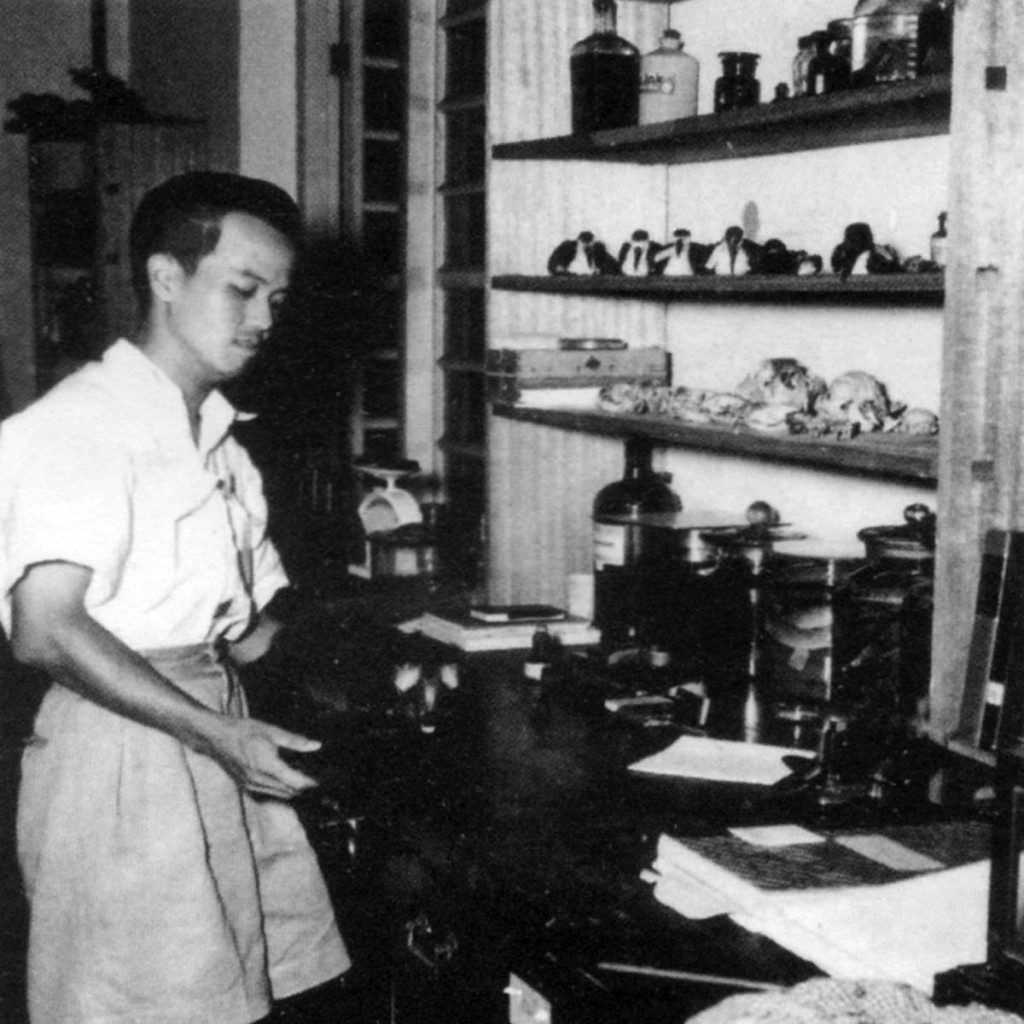

Dr Lim may not be that famous in the public eye – the only news stories we’ve found of him was of his recent death and from back when he received the Merdeka Award in 2013 – but in zoology circles, he’s said to be legendary. He had been researching animals for six decades, and his studies, which centered around small mammals and parasites, had been a huge help in understanding and protecting our biodiversity.

To rattle off all of Dr Lim’s accolades and achievements would probably make this article too cheong hei, plus we’re sure most people won’t get what’s so great about them anyway. Rather, we went through a small portion of the 300+ research papers and publications he had written over the years, read them through the eyes of a non-scientist, and highlighted some interesting things in them.

For one thing…

1. These Malaysian tupai actually prefers… meat?!

If you’ve hung out at parks or practically anywhere with a lot of trees, chances are you’ve seen this guy hanging around:

Looking at their bushy tails and their scientific name (Tupaia glis), you might be forgiven for calling them squirrels, but they’re not, really. They’re called tree shrews, which belong to a separate group of mammals. While squirrels are closer genetically to other rodents and rabbits, tree shrews are closer to primates, like us.

Unlike a lot of squirrels, they have pointier snouts and generally spend more time on the ground. And based on a 1995 research by Dr Lim, their eating habits are also a bit more… wide. Squirrels are often depicted eating nuts and fruits, but by examining the stomach contents of some common tree shrews, Dr Lim found not just fruit remains, but bits and pieces of other animals as well.

The most common animal remains were that of insects like beetles, caterpillars, termites, and even spiders. Less commonly found were pieces of crab and snail shells, toes of skinks (a type of lizard), and small rodent jaws, possibly those belonging to young rats. Based on this, it would seem that tree shrews like to eat bugs just as much as they like fruits, and a lab test confirmed this.

In the test, Dr Lim provided two common tree shrew couples with a selection of mealworms, crickets, cockroaches, snails, and mixed fruits; then he recorded how much of each food got eaten every day. While the tree shrews sampled everything they were given, it seems that they like bugs slightly more than they like fruits, with mealworms and crickets being their go to choice.

Speaking of eating bugs…

2. You can tell how animals behave in the wild from the parasites they have

Besides classifying animals neatly into a system, zoologists are also interested in their behavior, among other things. The most obvious way to know how animals behave in the wild is by hiding somewhere and watch them do their thing, but that’s not the only way. Zoologists can also piece together clues from what animals eat, and what parasites they picked up.

For example, taking their eating habits from earlier, it seems that tree shrews sometimes hunt baby rats to eat, and they may sometimes catch crabs while taking a drink from a stream. Skinks can often be found on forest floors under fallen leaves and logs, and the tree shrews might find them while looking for insects, which often hang out at the same place as skinks.

To piece together these clues would mean that zoologists need to have a good understanding of not just the animals they study, but the other animals living at the same habitat as well. Naturally, this extends to looking for clues from parasites as well. In his study about lesser tree shrews (Tupaia minor), Dr Lim found that some of the tree shrews were infected with three types of parasites, but a bigger number was infected with only one of these types.

Of these three types of parasites found, two were common, and one type was more often found in animals that live in trees, like squirrels. Since there were considerably more lesser tree shrews having only the kind of parasite found in tree dwelling animals, it can be deduced that this species spend a lot of time up in the trees, only occassionally going down to the forest floor.

Besides telling where animals like to hang out in their spare time, some parasites can also give a clue on what they eat.

3. We may be resistant to a kind of rat worm that live in snails

That sentence might sound confusing, so you should know that some parasites have to change hosts to progress in life. The rat lungworm, for one, start out their lives being pooped out by rats, then getting eaten by snails, then getting eaten by rats again before they can become adults and lay eggs. These worms were the subject of a 1967 research by Dr Lim and a D Heyneman.

In the experiment, they’ve found that if you feed a rat a large number of these worms at once, the worms will travel through the rat’s bloodstream all the way to the brain, where they will burst out of the brain’s blood vessels and cause the rat to die. However, by feeding rats small amounts of the worm several times, they built a sort of resistance to it, being able to eat more worms in one go without dying.

As for why that should matter, the rat lungworm can also affect humans, although to a lesser degree, causing headaches, fever, and sometimes an infection of the brain and nervous system called eosinophilic meningitis. This can happen when people eat infected snails. However, while neighboring countries have had quite a number of cases of eosinophilic meningitis, Malaysia had practically none, despite some of us eating masak lemak snails and whatnot. So what gives?

Well, it could be because the cases were unreported (the effects of eating the worms go away on their own without treatment). Oooor it could also be because we’ve unknowingly built up an immunity to the worms. Samples of lettuce bought by Dr Lim from markets in KL were found to contain traces of the worm, probably left behind by infected snails crawling over them.

It’s a possibility that by eating slightly tainted vegetables, we’ve became resistant to the worms, much like the rats in Dr Lim’s experiment. So maybe there’s merit in eating weird things after all, so…

4. If you want to eat this big rat, you’ll need some MSG

This probably wasn’t from a taste test or anything, but rather as a minor point within a piece on the kinds of rats and mice you can find in plantations and rice fields in Malaysia, written by Dr Lim. In case you’re wondering how many different kinds there are, the answer is five, but a normal person would call all of them rats or ‘tikus’ anyway.

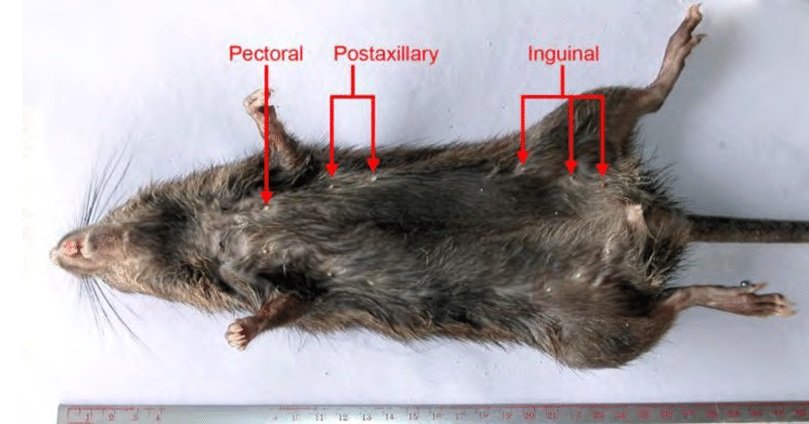

One of them is the greater bandicoot (Bandicota indica), which to be honest looks more like a giant rat and nothing like Crash Bandicoot. To be fair, the bandicoots we have aren’t the same as actual bandicoots, which are marsupials like kangaroos. Our bandicoots are just rodents, but if it’s any consolation, the marsupial bandicoots got their name from the rat bandicoots, so that’s kind of messed up, and we shouldn’t pursue this any longer.

Anyhoo, the paper has a section describing the role of these rats as food. In the World War II years, when meat was scarce, the larger of these rats, often the greater bandicoot, were often trapped and eaten in some countries. In one of his field activities, Dr Lim and his colleagues tasted a selection of properly boiled forest rats including the greater bandicoot. The taste, he reported, was bland in contrast of domesticated animals.

There’s more that we want to highlight, but this article is getting pretty long already. Still…

It seems that the late Dr Lim was pretty passionate about zoology

We can’t say that we know him personally, but reading some of his works and interviews, it seems like studying animals isn’t just a day job for Dr Lim. He was already interested in animals and their diversity long before he actually made it a career, and continued to contribute his time and energy in the field long past his retirement.

You can also see he was actually interested in what he’s studying by the way he wrote his findings, like in this excerpt from a study where he went into a forest to observe social interactions between several pairs of T. glis. For one pair, the male had tried to court a female and was almost succesful, when:

“…they were suddenly alerted by an intruder, a Long-nosed Ground Squirrel (Rhinosciurus laticaudatus) who came out from the thickets… Upon the approach of this squirrel, the male emitted a high pitched call with his mouth open probably expressing extreme anger at the intruder for intruding into their privacy…” – Lim Boo Liat, ‘Field Observation on the Social Behaviour of the Common Tree Shrew (Tupaia glis)’, The Journal of Wildlife and Parks, 1995.

Being such a passionate and enthusiastic wildlife researcher and advocate, Dr Lim’s passing is surely a significant blow to the zoology community. However, it should be safe to say that he had left behind more than just a tiny mark on the local zoology scene. And it’s not just from his 300+ publications, either.

“…perhaps Lim’s greatest legacy has been his role in nurturing and guiding the next generation of biologists and conservationists. Always generous with his time and experience, he will be remembered with fondness by so many as a mentor and a friend.” – The Habitat Foundation, in a Facebook post.

If that’s not a life well-spent, we don’t know what else would you call it.

- 2.5KShares

- Facebook2.4K

- Twitter11

- LinkedIn16

- Email20

- WhatsApp40