Is Malaysia the worst country in ASEAN for women in politics?

Have you ever noticed anything off about our Parliament? Let’s start with a pop quiz for you: look closely at the picture above. Do you see anything wrong? Anything, or anyone missing? Or maybe, it even looks completely normal to you.

If you figured out that there are barely any women, you’d be so right. And by barely, we mean it! Out of the 39 MPs in that photo, only 3 of them are women.

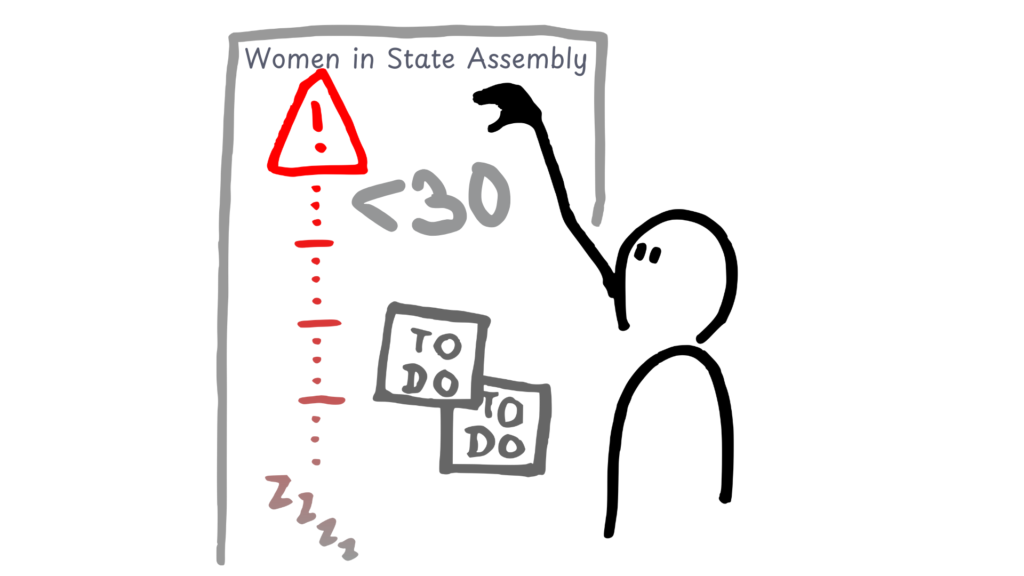

If you’re thinking “Eh, that’s kinda weird and unfair”, so did we! I mean women make up almost half or 48 percent of the total population. But right now, we have 222 Members of Parliament, of which only 30 are women. That’s just over 13 percent, a sad number.

So all of this made us start wondering, has it always been this way? Does it matter if women are underrepresented in politics? And if so, is there anything that can be done to fix this? Well..

Let’s start with the state of Malaysian women in politics.

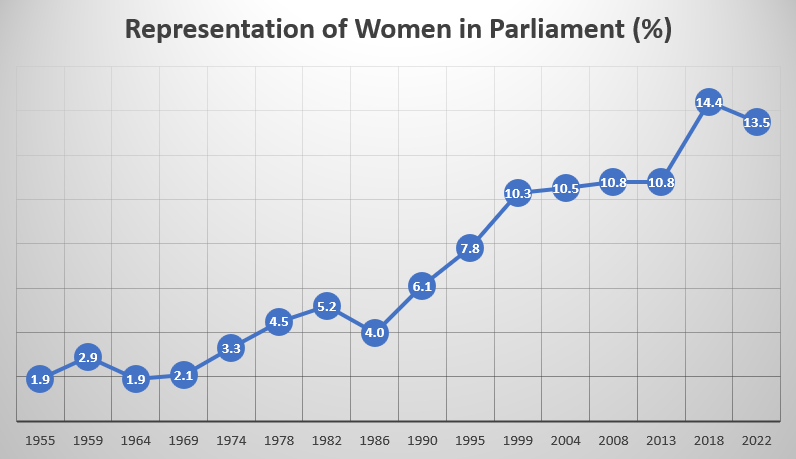

You might be surprised to know that for the last 70 years, women have never made up even 20 percent of MPs in Malaysia. In fact, 20 percent is pushing it.

According to research done by Yeong Pey Jung for the Penang Institute and Westminster Foundation for Democracy, the highest we ever got was just over 14 percent in 2018.

That’s basically the same as randomly pulling twenty people from a Dewan Rakyat sitting, and finding three women in the group.

Still, 14 percent is much higher than the lowest we ever had in Parliament, which was 1.9 percent back in 1964 when there were really were only three women along with 156 men in the Dewan Rakyat.

Now you might be thinking, “Okay la, so we’ve improved since then?” I mean we’ve gone from less than two percent of MPs being women to all the way up to almost 15 percent!

Which would be impressive if again, women didn’t make up about half the country, and if you consider the current goal set by the UN for women representation in politics is 30 percent, which is more than double our highest number.

In fact, things look even worse if you look at how we’re doing compared to other countries.

According to rankings by the Inter-Parliamentary Union, we’re beat by a bunch of our neighboring countries.

This includes Thailand which has close to 20 percent of women representation in Parliament, Indonesia at 22 percent, Philippines with 28 percent, and even Timor-Leste (who just joined ASEAN like, yesterday) with 35 percent!

In fact, out of the eleven countries in ASEAN, we rank second last, just above Brunei.

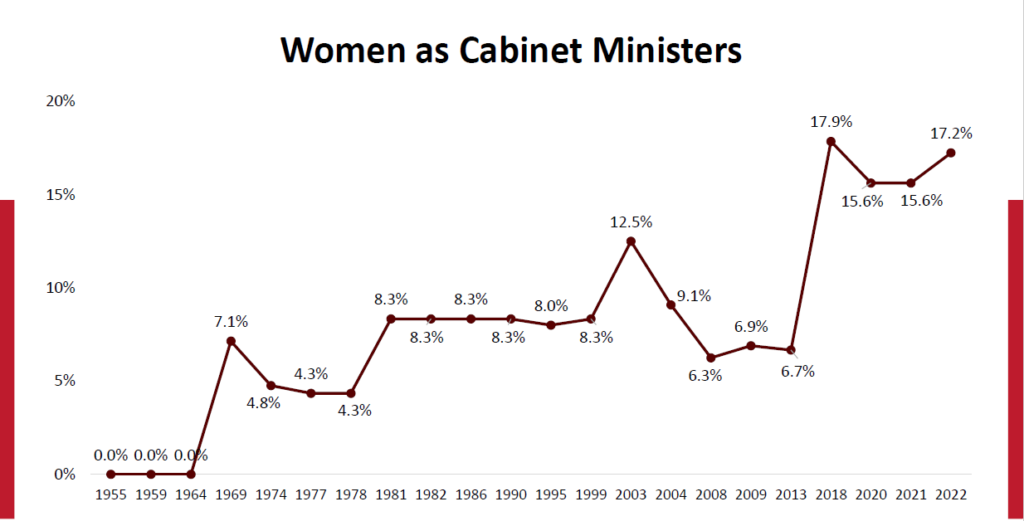

Now as for women becoming ministers, things haven’t been much better either. For example, in the cabinet, it took til 1969 for us to get our first female minister – Tun Fatimah Hashim, who was then appointed to become the Minister of Welfare.

Since then, although we’ve included more women in the Cabinet, the numbers have not been that encouraging.

The highest representation of women ministers we’ve had was almost 18 percent in 2018 while currently, out of the 31 Ministers we have in Cabinet including the Prime Minister, just five or 16 percent of them are women.

It’s worth noting that we currently have the highest representation of women that we’ve ever had among Deputy Ministers at just about a fifth, which still kinda sucks because like, no one really cares about deputies.

Which brings us to the next question, so what? What’s the big deal with having more women representing us in Parliament?

Because these have actual implications in terms of the decisions that get made.

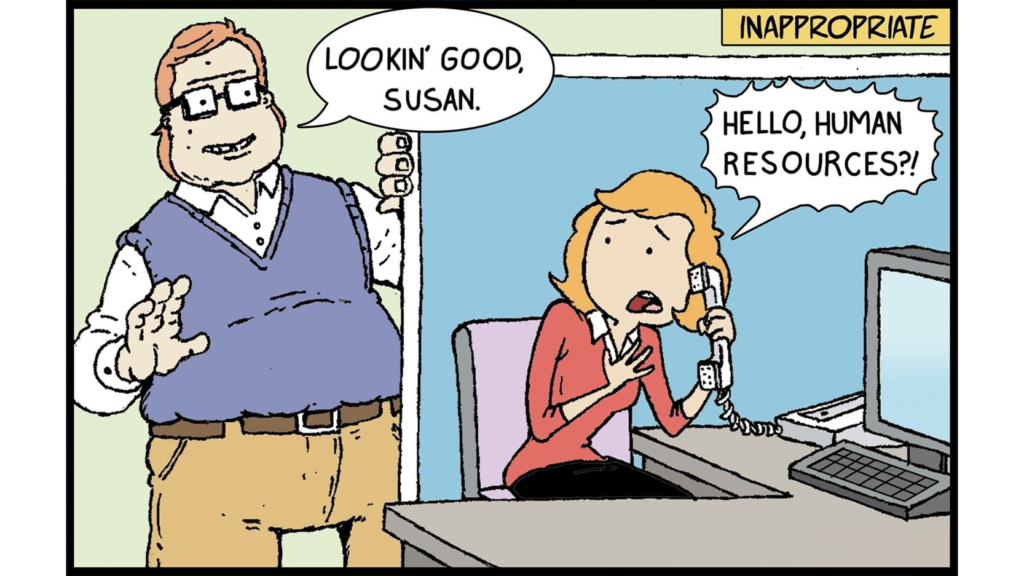

Consider for example how it took us over a decade to make sexual harassment illegal.

The lobbying for standalone anti-sexual harassment protections actually began all the way back in 2011, but it wasn’t until 2022 – yes, that’s barely four years ago – when the Anti-Sexual Harassment Bill finally saw the light of day.

That’s more than ten years passing since we first decided to do something about women (and let’s be real, men too) getting harassed by weirdos.

Why did it take so long? Well probably because it was an issue that primarily impacted women.

According to a 2020 survey of a thousand women by the Women’s Aid Organization, 62 percent of them said they’d experienced one or more forms of sexual harassment in the workplace, whereas according to another survey by YouGov, it was found that over a third of Malaysian women had experienced sexual harassment compared to just one out of six men.

Really think about it. Think about all the women you know and how basically half of them would’ve faced this at some point.

Despite that, the bill was shelved, delayed, and pushed to the bottom of the priority list like the half of that onion that’s been in my fridge since 2024.

And it wasn’t until female MPs from across party lines, together with civil society, began pushing relentlessly, that the bill finally crossed the finish line.

Now, if we had more women in Parliament from the start, would this have taken as long as it did? We’ll never know for sure, but what we do know is again and again, issues that disproportionately affect women tend to be the ones that get delayed or ignored.

Another example, how for years, Malaysian fathers were able to pass on citizenship rights to their children born overseas, but if you were a mother married to a foreigner, you couldn’t do the same for yours.

Or another one, child marriage, which according to UNICEF, disproportionately affects adolescent girls in rural areas, and how it’s still legal here in Malaysia under both civil and syariah law, despite experts calling for it to be banned due to overwhelming evidence of its harms.

And the pattern here is clear. Because when the people in charge of making the laws are mostly men, the ones having to pay the price end up being women and girls.

What can we actually do about it?

Thankfully, there’s a pretty straightforward fix to this.

According to Pey Jung, whose research we quoted, we could implement a mandatory 30 percent quota for women candidates by political parties during elections.

The UN has been calling on governments to do this since like 1990, and in the 2009 National Policy on Women, Malaysia also did the same by adopting a 30 percent target for women in Parliament.

In fact, there are even NGOs like EMPOWER who are pushing for all political parties to field at least 30% women candidates by GE16.

Now the obvious problem is, MPs are elected by voters. So unlike Ministers or Deputy Ministers who can just be appointed, it doesn’t matter if the government sets that target for Members of Parliament or State Assemblies.

Ultimately, whoever becomes an MP or ADUN can only do so if they win an election.

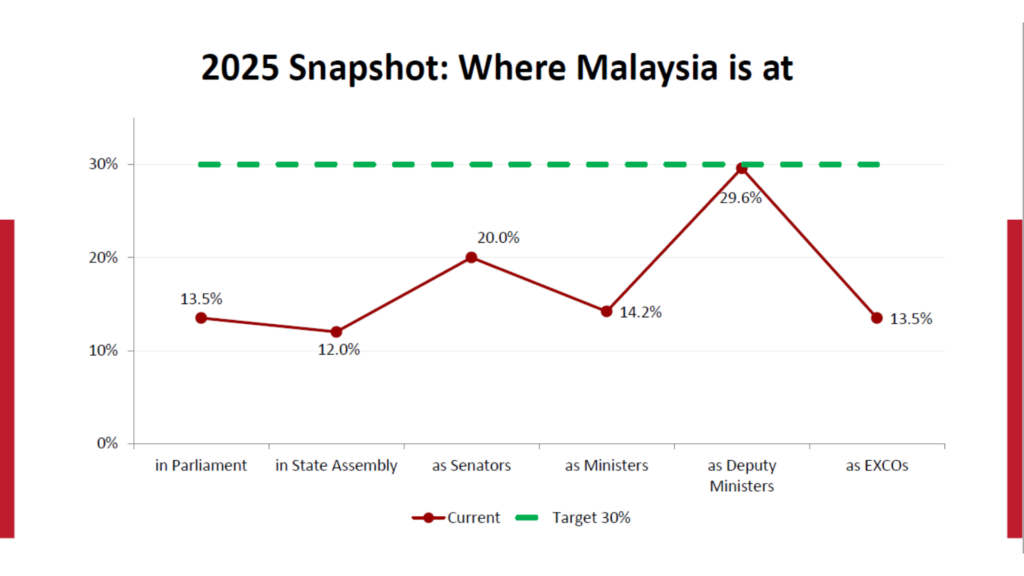

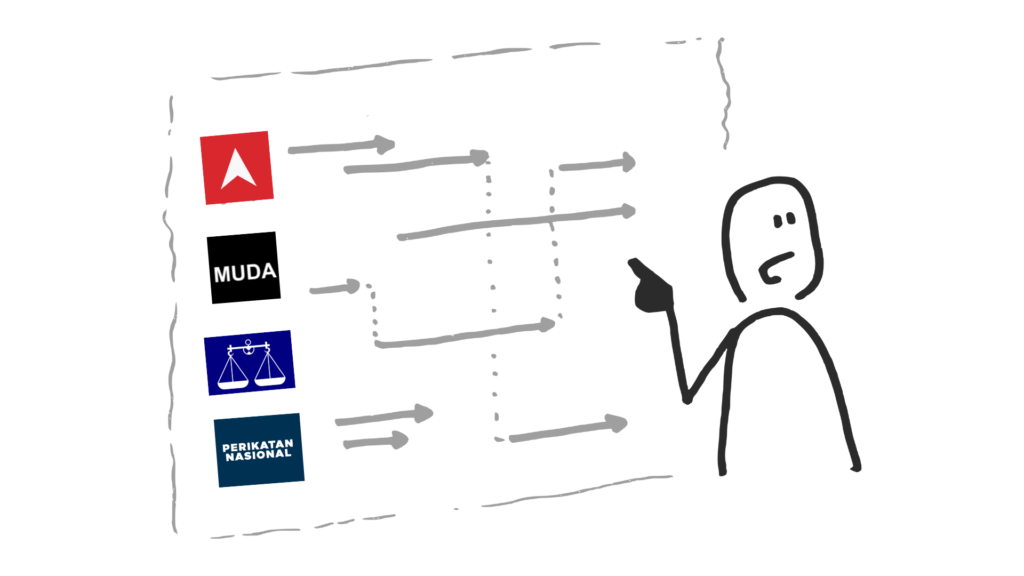

We can see how this can be a pitfall in this chart below.

Offhand, we can observe that the lowest proportions of women are in Parliament and State Assemblies, compared to higher representations of women as Senators, Ministers and Deputy Ministers.

Now, what does all this actually mean? Do voters just not wanna choose women to represent them? Well, that’s not entirely true.

Because, for example if we look at the data from GE15, out of the 945 candidates that were fielded in the elections, only 127 of them were women.

Again, that’s pretty much just 13 percent of women being chosen to become candidates.

I mean, how are you expecting women to score goals when you won’t even let them on the field?

Which is why the 30 percent target Pey Jung talks about isn’t just for women in Parliament, but for women candidates in elections period.

So, while a mandatory quota might seem harsh, it might be necessary because women often don’t even get a chance to be in the running in the first place.

Other suggestions have also been made for how to increase women representation, one of which is by, Project SAMA, which is an NGO advocating for political reform in Malaysia.

Basically, they’ve pushed for something called Top-UP Woman-Only Additional Seats to be considered in Penang. Now how this would work is this:

Before the election, every party submits a ranked list of women candidates.

After the election, if women still make up less than 30 percent of the state assembly, extra seats are added.

Those seats then get allocated to parties based on the percentage of votes they received, and filled using their women’s list as statewide, non-constituency representatives.

This would incentivize political parties to nominate women candidates that they otherwise would not, and ensure the minimum representation of women in the State Assembly, without disrupting the existing system or requiring a whole separate election.

Of course, quotas alone won’t fix everything.

We haven’t even touched on all the things we would need to do as a society to encourage girls to step into leadership from an earlier age, or to remove the barriers that stop women from achieving their potential.

But until we decide that this is something we actually want to take seriously as a society… we’re going to keep watching the men scream at each other in Parliament, all while wondering why nothing actually ever changes.