500,000 Malaysians suffer from Hepatitis C. And the gomen just made treatment 99% cheaper.

- 728Shares

- Facebook668

- Twitter10

- LinkedIn10

- Email17

- WhatsApp23

When talking about expensive stuff, most people would imagine fuel or the new iPhone or higher education (or the loans). But if you have a chronic disease (or know someone who has one), chances are you’d imagine a box of pills.

So when the government announced that they will be able to reduce the price of a Hepatitis C drug by 99% by the end of this year, it’s something worth talking about. In an announcement to the press, our Health Minister Dr S Subramaniam had stated that the cost of treating Hepatitis C will be dropped to RM500 per person, from the initial price of RM50,000. The cheaper drug will be only available at public hospitals for the time being, and it is estimated that the reduction will benefit some 500,0000 sufferers.

“Hepatitis C has become a major public health concern in Malaysia, therefore it is crucial to increase access to treatment for the benefit of the nation,” – Dr S Subramaniam, as reported by FMT.

For those not familiar with the disease, Hepatitis C is an inflammation of the liver caused by the Hepatitis C virus (HCV) which is transferred through blood. In chronic cases, patients will almost always develop liver cancer or cirrhosis, where the liver becomes so scarred that there are more scar tissues in the liver than actual liver tissues.

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that around 71 million people are living with a chronic Hepatitis C infection, and some 399,000 people die each year from it. While there are vaccines available for Hepatitis A and B (and limited availability for E), there are currently no vaccines for Hepatitis C, so it’s not preventable yet. Treating it consists the use of direct-acting antivirals (DAA), which basically means that patients will have to eat a pill periodically until all the HCV in their bodies die out, and this works 95% of the time.

Globally, the drug, named sofosbuvir (brand name Solvadi) goes for around $1,000… per pill. So for people who suffer from Hepatitis C, the news of a 99% discount is fantastic, right? How is the government doing this? And why does the drug cost so much in the first place?

Life-saving medicines are expensive, and the reason for that is patents

Just like how there are real and imitation LV bags out there, there are brand-name and generic drugs. And just like how most people won’t be able to tell the difference in form or quality between the two LV bags, the difference between brand-name and generic drugs are often only in price. So if generic drugs are just as good as brand-name drugs, why aren’t more hospitals using generic drugs?

The reason for that is somewhat of a legal thing. Brand-name drugs often had a patent on them, which is like a copyright of sorts. When a pharmaceutical company discovers a new drug, they will usually file a patent that prevents other companies from making the same drug. This effectively gives them a monopoly on that drug, so basically they can set the price to whatever they want. Patents help pharmaceutical companies to recover the cost of research for the drug and make some money for the companies’ shareholders, at least until the patent ends.

Generic drugs, on the other hand, are usually many times cheaper as manufacturers do not have to start from scratch on the research process. Also, since there are usually many companies manufacturing a type of generic drug at any given time, competition between them further lowers the price. However, generic drugs can only be manufactured after the patent for the original drug had ended, and this could take decades.

Using or making a generic drug before the original patent ends is obviously an infringement of patent laws. Unless, of course, if you invoke some laws to help you out.

Our Patents Act kinda allows for copyright infringements

Maybe when reading about the subject matter, you’ll hear something along the lines of ‘government use‘ or ‘compulsory license‘. Also, ‘voluntary license‘, but we’ll get to that later. But what in tarnation do they all mean?!

Basically, government use licenses and compulsory licenses are the same thing, and they allow the government to bypass some patents in special circumstances. Specifically, the Patents Act 1983 (Act 291), Section 84 deals with rights of the government to exploit a patented invention even without the permission of the patent holder, provided that

- there is national emergency or where the public interest, in particular, national security, nutrition, health or the development of other vital sectors of the national economy as determined by the Government, so requires; or

- a judicial or relevant authority has determined that the manner of exploitation by the owner of the patent or his licensee is anti-competitive.

Of course, there are other things in the section that lays out what the patent owner can do, and how the government should pay the patent holder some form of renumeration, but essentially that’s what a compulsory/government use license is. If patents are like a river that flows between a government and a medicine, a compulsory license can be likened to a bridge crossing that river. Governments can practically get to the medicine without getting wet.

And this isn’t just a Malaysian thing, either. Back in 2001, something called the Doha Declaration came into being. While the name may sound intimidating, basically it’s a sort of agreement between countries that says, among other things, that member countries have a right to protect the health of their citizens, and patents should not stand in the way of that.

You can read about the Doha Declaration in more detail here, but the point here is that the declaration allows for some flexibilities regarding copyrights and intellectual properties when it comes to medicine and drugs, and one of them is allowing members to grant compulsory licenses, and set the conditions for it themselves. So yeah, compulsory licenses are totally legal internationally. However, just because something is legal, it doesn’t mean that everyone (read: drug companies) will be happy with it.

So what other alternative is there? Well, there’s voluntary licensing.

At first, Malaysia didn’t qualify for a voluntary license

If a compulsory license is like a bridge over a river of patents, a voluntary license can be likened to a sampan that crosses that river, subject to the flow and eddies of the river. A voluntary license is sort of like a permission for manufacturers in a certain country to make, sell and import generic versions of its drugs, often under terms and conditions set by the patent holder. You can still cross the river, but it’s a bit harder in a sampan than by using a bridge.

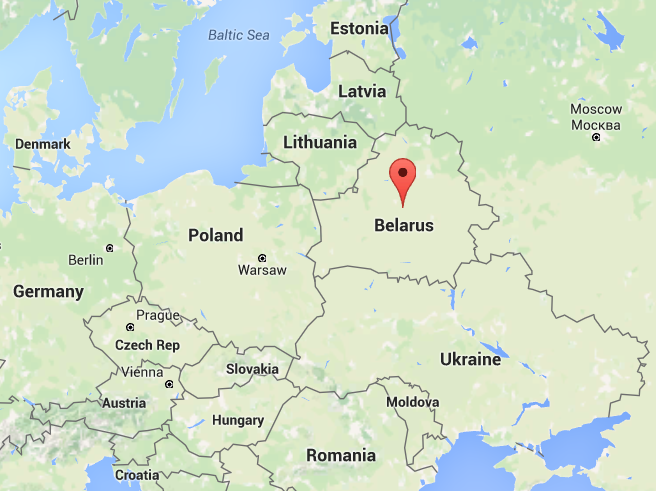

Initially, Malaysia tried to get a sampan from Gilead, the company that created the Hepatitis C drug sofosbuvir, but it failed as Malaysia is a middle-income country. That failure caused the gomen to start building a bridge instead. However, just after the MOH decided to do that in August, Gilead announced the extension of its voluntary license offer to four middle-income countries, which are Malaysia, Thailand, Ukraine and Belarus.

This sudden move was seen by many as a form of damage control to discourage other countries from coming up with compulsory licenses of their own. After all, if Malaysia can just import cheap generic medicines from India, why should other countries pay full price for their medicines?

“The decision to include these countries, however, no doubt is a response to increasing pressure from within these countries to either issue a compulsory license or a government use license, invalidate the Sofosbuvir patents, or block data exclusivity for the drug,” – Fifa Rahman, former manager for access and affordability for hepatitis C drugs at the Malaysian AIDS Council, as reported by Intellectual Property Watch.

After that announcement, the Malaysian gomen now had two choices: either accept the voluntary license offered by Gilead, or go ahead with the compulsory license. Malaysia chose the compulsory license. This is a move lauded by many, as a compulsory license has certain advantages over a voluntary license.

Martin Khor, the executive director of the South Centre, had pointed out that accepting a voluntary license may limit what Malaysia can import or produce under the Gilead license. It can also limit the gomen’s freedom of choosing which generic manufacturer firms it wants to work with.

“With a government-use licence, the Government will have freedom to choose which drug to buy from which firm, at what prices, and with which other drugs to combine it.” – Martin Khor, for the Star.

Cheaper drugs, freedom of business, and it’s all perfectly legal by international law. No downsides there, so one might wonder…

Ehh… so why aren’t we making more drugs cheap?

Klang’s MP Charles Santiago had also lauded the move by the government and said that the use of government licenses should not just stop at Hepatitis C medications. In a statement to FMT, Santiago suggests that the same thing should be done for cancer medication as well.

“It is estimated that about 100,000 Malaysians live with cancer at any one time and it is the third biggest killer in the country. Some statistics show one in four Malaysians will have cancer by the age of 75.” – Charles Santiago, for FMT.

While Santiago had pointed out that the concerns of cancer patients such as the high cost of medication and disrupted incomes are no less daunting than those of Hepatitis C patients, some are of the opinion that we should not be invoking the government use license willy-nilly.

Azrul Mohd Khalib, the CEO for the Galen Center for Health and Social Policy, had stated that while he welcomed the move by the government, the decision to use a government license may affect other innovations that depend on patents to protect their intellectual property.

“Malaysia’s reputation in intellectual property rights will take a hit, especially as it has decided to proceed with this action despite its recent inclusion into Gilead Science’s voluntary licence programme. For better or for worse, Malaysia’s action will also have a ripple effect across countries in the region. We might see other countries deciding to do what Malaysia has done.” – Azrul Mohd Khalib, for FMT.

Fifa Rahman felt that countries try to avoid using compulsory licenses as they fear it may affect their international trades. However, Fifa had noted that not only is the fear of trade retaliation unjustified, the recent experience showed that the threat of a compulsory license caused a patent holder to voluntarily include countries in their licensing schemes, resulting in a reduction in medicine prices and increased medicine access.

At the end of the day, the drug industry is a business after all. While it can’t be denied that this move by the Ministry of Health could potentially save a lot of people living with Hepatitis C by making the treatment more accessible to them, giving out compulsory licenses isn’t as simple as Hepatitis A, B, C.

- 728Shares

- Facebook668

- Twitter10

- LinkedIn10

- Email17

- WhatsApp23