Up until 40 years ago, ‘pengangkat najis’ was an actual job in Malaysia.

- 295Shares

- Facebook272

- Twitter5

- LinkedIn4

- Email6

- WhatsApp8

[Artikel ini ditulis berdasarkan artikel sama oleh member-member kami kat Soscili. Kalau nak baca artikel ni dalam BM, klik sini!]

*old man living in Klang Valley voice* “Haiyoh kids these days so lucky one. No need to walk five hundred miles to go to school. No need to poop in buckets or carry buckets of crap for a living. No need to rebus the egg to put the yolk in your computer mouse. So soft la these strawberries!”

We’re sure you’ve heard some version of old people complaining like this, and sometimes it’s hard to tell how much of their epic tales of struggle is real. But if they talked about pooping in buckets, that might be a very real experience. After all, sewerage systems don’t just magically appear in the ground, and before Malaysia became what it is today, people have to poop in some way.

While in the rural areas it’s not uncommon to make do with rivers, holes dug in the ground, or squatting over precarious precipices, picking the perfect place to put out a pile may not be so painless for people populating the new towns of 1900s Malaya.

To address this crappy crisis, a new job was created. One that was literally the shittiest job ever.

Nightsoil carriers: the people who shouldered your buckets of crap

If you’ve watched P. Ramlee’s Tiga Abdul, you might have heard a passing mention of this job: when introducing the servants to his wife, the main character refers to his father-in-law as a ‘pecacai tua pengangkat najis‘ (old poop-carrying slave), translated as ‘scavenger’ in the subtitles.

While it may seem weird to hear it today, poop carriers were actually a real career back then, although they were more formally referred to as nightsoil carriers/laborers, with ‘nightsoil’ being the euphemism for human poop. In the absence of modern toilets, many houses would have a bucket in their toilet to poop in. Every day, in the wee hours of the morning, nightsoil carriers would show up to these houses and collect the buckets. A detailed documentary by PURGE went more in depth on how they work in Penang, but based on their interviews, it’s one of the toughest jobs we’ve heard of.

Due to not many people wanting to take the job, nightsoil carriers often worked seven days a week, and the ones interviewed by PURGE even worked throughout the 13 May 1969 incident, because riot or not, people still poop. These people worked from early morning until about noon, after which they’re free to take on another job or rest. But the job sounded traumatic enough, even with the short working hours:

“I remember I cried on the first day at work. The smell was unbearable.” – Mr Kathy, former head of a nightsoil carrier team, in an interview with PURGE.

Besides being hard, it’s a thankless job as well. Nightsoil carriers were seen as the very bottom of the society, with a study in the 1960s on occupational prestige among Malaysians putting nightsoil carriers in the bottom 6 least prestigious jobs, along with beggars, petty thieves, brothel keepers, prostitutes, and trishaw paddlers. Reportedly, most of the people in this line of work were Chinese immigrants, although there are rare instances of other races taking it on, due to the stigma.

Still, someone had to do the job, and it’s thanks to these poop carriers that early Malaya didn’t get completely buried in crap. Which brings us to an interesting point…

What do they do with the poop they take away?

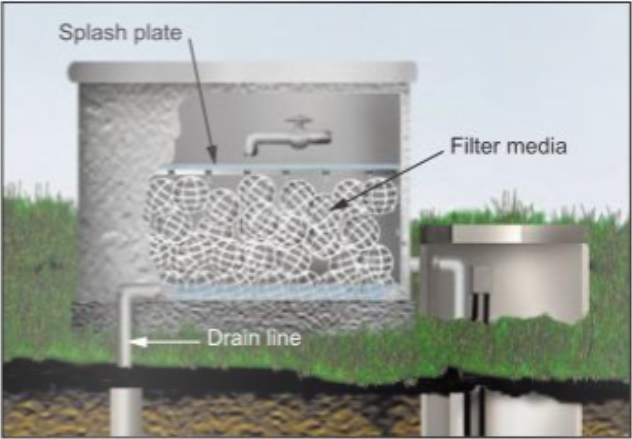

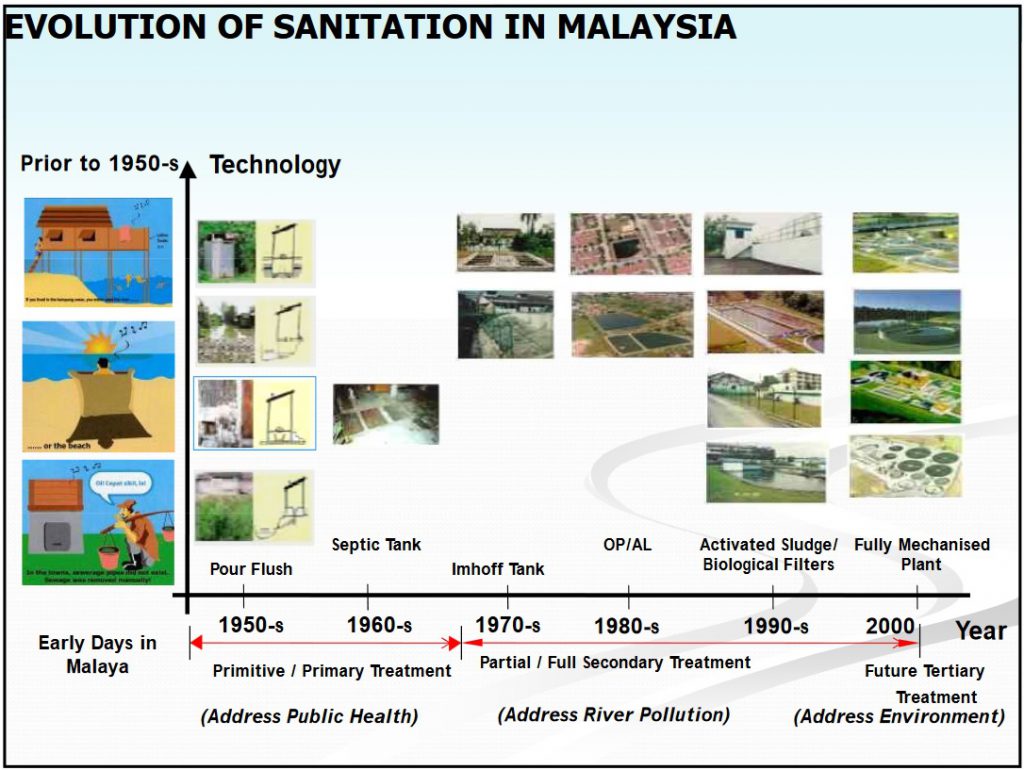

Just to be clear, poop buckets weren’t the only nightsoil disposal systems in force back then, but it seemed to be the most advanced one we’ve got by the late 1920s. In December 1930, a hygiene professor called A.D. Stewart toured Malaya, and he noted that none of the towns had complete sewerage systems. Some buildings (like hotels and government buildings) were already employing small septic tanks or a trickling filter system, where the wastewater was filtered before being released into surface drains.

The poop from the bucket system was put through the same thing, albeit at a larger scale. In Penang, for example the nightsoil was collected by laborers on trucks – these are called ‘honey wagons‘ in Singapore – and taken to depots, where it got poured into large septic tanks with trickling filters. The resulting treated water was later released into the sea. The collection service apparently costs around $1 per month in Penang, dubbed the latrine tax.

In KL and Ipoh, the collected poop was trenched, which is essentially digging a trench somewhere and burying the poop there. Interestingly, these areas used a double bucket system, where clean, different colored buckets were taken to the houses and exchanged for the dirty buckets each day. The dirty buckets were taken to a bucket washing station, where the contents were combined and taken to the trenching site. The emptied buckets were then cleaned for the next day, and the wastewater from washing the buckets were sent to septic tanks and their trickle filters.

It should also be noted that in some rural areas, the collected poop was dumped in large, well-like holes, and some farmers use the nightsoil as fertillizer for agriculture. This practice, along with the general fashion of not wearing shoes during the era, contributed to a massive hookworm problem: 73.3% of the Straits Settlements’ inhabitants were found to be infected in a 1925 survey, while 90% of Malacca’s schoolchildren had the parasite. There were also the general practice of using nightsoil to fertilize fish ponds in Southeast Asia, leading to the prevalence of another parasitic infection called human echinostomiasis.

Yeah, generally it wasn’t a hygienic time to be in, by today’s standards. But thankfully…

We’ve since moved on to less shitty options

It wasn’t really clear when we completely abandoned pooping in buckets – the PURGE documentary mentioned that they had to work through the 1969 riots, and mentions of the job persisted in Singaporean newspapers up until 1987. But we should note that progress was happening even during the height of the poop bucket system, as the system wasn’t meant to be a permanent solution to poop: it was just until proper sewerage and water treatment infrastructure can be built.

Stewart, for example, mentioned of a new system being experimented on in Penang during his visit, called the bored-hole latrine. These were really deep holes in the ground (reaching 25 feet deep), with a mix of kerosene and crude oil poured into them to stop flies from breeding. People would poop in this hole, and when the pile of crap inside gets near the surface, these toilets would be temporarily closed off for a month or two to allow the nightsoil to disintegrate. They still required manpower to operate, though: a sweeper to keep the concrete seats clean.

Since then, both our toilets and our sewerage system – in most of Malaysia, anyway – had evolved by leaps and bounds to become what they are today. But that’s another story for another day.

For now, let us appreciate the joy of pooping into clean toilets, blissfully unaware of our poop’s craptacular journey through the sewers. And maybe listen sympathetically the next time an old person complains about our generation’s pooping habits.

- 295Shares

- Facebook272

- Twitter5

- LinkedIn4

- Email6

- WhatsApp8