Is a 1980s shipping policy causing Malaysia to lose FB & Google’s undersea cable projects?

- 4.6KShares

- Facebook4.4K

- Twitter20

- LinkedIn18

- Email18

- WhatsApp99

[This article was originally published in March 2021. It has since been edited to reflect current events, namely the Apricot cable.]

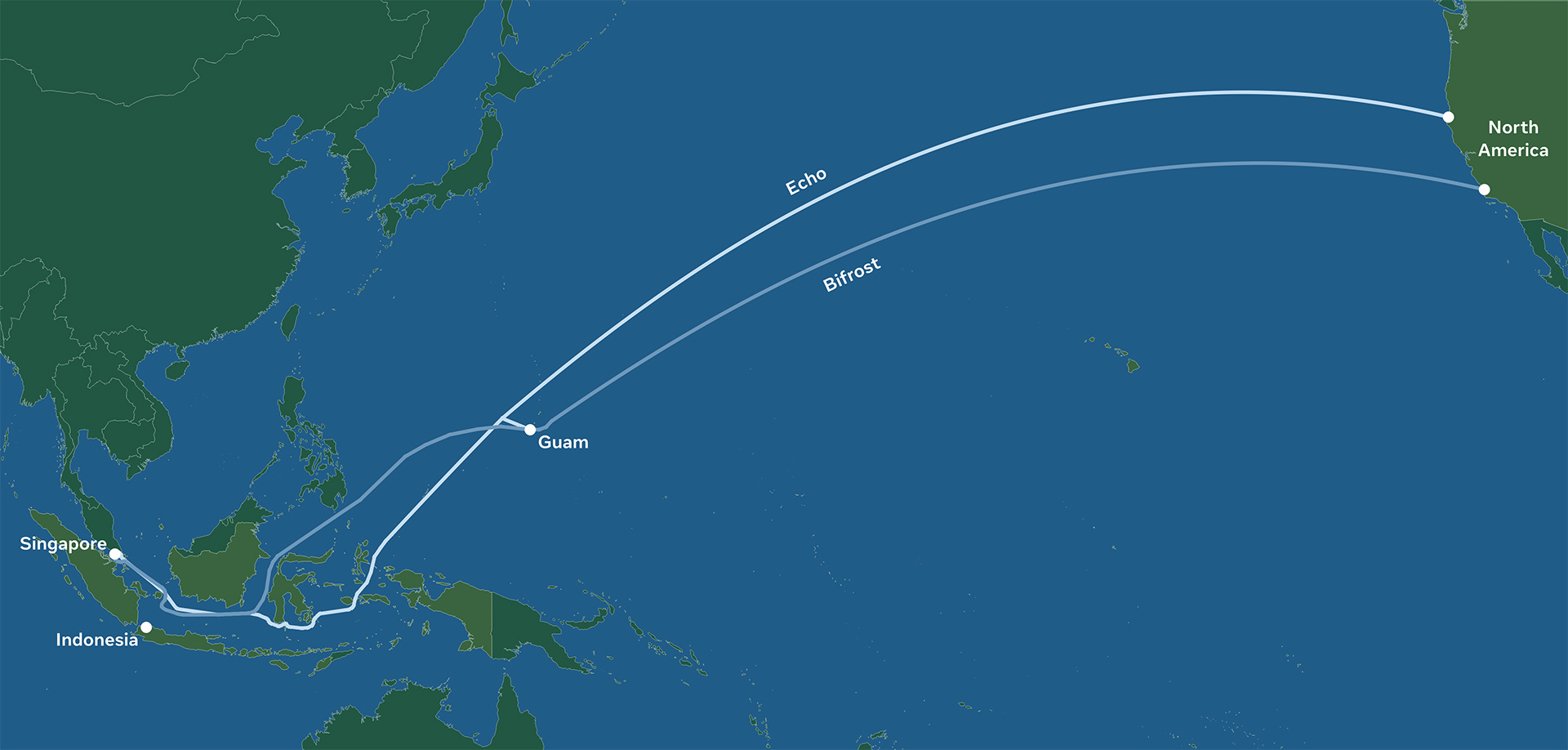

So sometime in March this year, Facebook and Google announced their newest project, two undersea cables (aka submarine cables) directly connecting North America to Indonesia and Singapore. These cables, named Echo and Bifrost, are huge investments by tech giants in the region and will boost the internet connection capacity in both those countries.

When the news broke out, MyIX, a local association of internet service and content providers, had lamented the loss of foreign direct investments (FDI) to neighboring countries, despite our strengths in attracting them.

“We lost out here. It’s a shame as Malaysia has our strengths in internet infrastructure due to our strategic geographical location, ease of access, English-speaking population and relatively lower cost of entry. In my view, this ‘big win’ for Indonesia and Singapore marks a significant loss for Malaysia.” – Chiew Kok Hin, MyIX chairman, as quoted by Malaysian Wireless.

More recently, in August they’ve announced Apricot, another subsea cable that will connect Japan, Taiwan, Guam, the Phillipines, Indonesia, and Singapore… but again, not Malaysia. Apricot is expected to provide a capacity of more than 190 Tbps to meet the rising data demands in the region as well as to support Echo and Biforst.

The crux of the issue here is ‘Eh? So why didn’t they connect to Malaysia?‘

The controversial answer to that question is ‘because our current government changed the cabotage policy, and it’s driving foreign investors away‘.

The sorta official response to that controversial answer is that ‘the previous government were too focused on flying cars to improve our data centers‘.

That’s a lot to take in all at once, so to fully appreciate this messy drama, first we have to address an important question…

What’s this cabotage policy, and why is it causing so much drama?

In very simple terms, cabotage concerns the rights of a country to control which ships get to carry passengers and cargo within its waters, although in some countries cabotage can also include control over airways, railways, and roadways as well. Malaysia came up with its own cabotage policy starting 1980, and it was designed to give Malaysian ships and ship companies an edge when it comes doing ship stuff. To say it in a needlessly dangerous way, think Bumi rights, but for local ships vs foreign ships.

To illustrate how that would work, trade between domestic ports (like between Selangor and Sarawak) can only be done by Malaysian ships, or one owned by a Malaysian shipping company. Up until 2019 at least, foreign ships carrying goods from outside must all go to Port Klang, which is the national off-loading centre, and the goods will then be put on Malaysian ships and carried to other places in Malaysia. However, the International Trade Ministry’s website stated that this is not the case anymore, and that foreign ships can also operate domestically as long as they’ve been granted a license by the government.

Okay, but what does this policy have to do with the recent cable drama? Well, you need special ships to install and repair underwater internet cables, and for some reason, Malaysia’s cabotage policy extends to that as well. If a foreign company wants to work on submarine cables in Malaysian waters, they have to either use a local ship or apply for something called a domestic shipping license (DSL) for their own ships.

However, it was said that this red tape caused a lot of delays, so much that cable repair times in Malaysia were among the highest in the region, averaging 27 days. By comparison, repair works in the Phillipines only took an average of 20 days, and Vietnam 12 days. People complained, so to speed things up, in 2019, the Transport Ministry (then under Anthony Loke) declared an exemption for foreign ships repairing cables in Malaysia.

Last year, however, the Transport Ministry (under Wee Ka Siong) revoked that exemption, so foreign companies have to again apply for DSL to repair their cables in our waters, although that process may now be faster since an online application system had been introduced. An alternative would be to use a local ship, but there’s only one company with the assets to do cable repairs, and their vessels (2) were said to be inadequate for the insurance requirements of tech giants.

Anyways, the revocation became a big deal, and tech giants like Microsoft, Google, Facebook, and MyIX, which is a local association of internet service and content providers, raised their concerns about it and tried to get the government to reconsider. They called the decision abrupt – it wasn’t announced to the public – and questioned why it was made without consulting the relevant stakeholders.

Well, that’s the gist of the background, more or less. If you want more details, check out SoyaCincau – they covered the issue pretty extensively, and in way more detail. This is just a quick guide so you don’t get clueless when you lepak with your friends and they suddenly got too high or too drunk and started talking about cabotage.

Getting back to the story, despite tech giants and industry players calling for the government to reconsider the reversal…

The government had insisted that our cabotage policy isn’t a problem

Wee had been firm in his decision to withdraw the cabotage exemption, saying that restrictions over cable repair ships isn’t a uniquely Malaysian thing, and it’s important to our digital sovereignty that we have cabotage restrictions. Besides saying that some arguments posed against the cabotage restriction was illogical, he had also mentioned that having a Malaysian-flagged vessel supporting these tech giants is actually a good thing, although he didn’t elaborate why.

“The crux of the issue is not about the relaxation of the exemption from the cabotage policy. We are actually giving them (the tech giants) a better deal… don’t you think they would prefer to have a Malaysian-flagged vessel to support them?” – Wee Ka Siong, in an interview with The Edge.

While the issue had been festering since earlier this year, the drama reached a head recently with Facebook and Google’s announcement of the new cables, and MyIX’s statement that implies we’re missing out because of our cabotage policy. Then Anthony Loke shared a SoyaCincau article about that on his Facebook…

Thanks to Wee Ka Siong for his “brilliant” strategy of protecting one company at the expense of the nation’s interest!

Posted by Anthony Loke Siew Fook on Thursday, April 1, 2021

…and Wee Ka Siong wrote a lengthy FB post in response. According to his post, the Echo and Bifrost projects had been planned since back in 2015, and that the reason why Singapore was chosen instead of Malaysia was because Facebook had already built a data center there, and we don’t have adequate data infrastructure anyways.

“The data centre is in Singapore, not Malaysia. We lack data infrastructure. For example, between 2018 and 2019 (Pakatan Harapan government’s era), Malaysia was wasting time and money on outdated ideas to develop flying cars instead of data centres and the industrial revolution 4.0,” – Dr Wee Ka Siong, translated from his FB post.

He also threw some serious serious shade at SoyaCincau, saying that the portal is a ‘suspicious’ and ‘non-credible’ source. In response to Wee’s response, SoyaCincau had posed three questions to the Transport Minister – has his ministry addressed the tech giants’ concerns, does Malaysia have the vessels for the job, and how can Malaysia attract more submarine cable landings – and invited him to their platform to elaborate further. As far as we can tell, the questions have yet to be answered.

We wouldn’t be surprised if the drama ends there, but the problem still remains…

Is now the right time for protectionist policies?

While there may be some merit to having the cabotage exemption for cable repair ships revoked, apart from the government and the Malaysian Shipowners Association (Masa), a lot of people felt that the decision will just harm Malaysia’s attractiveness to foreign investors. In a world where there are plenty of shops selling bread, would you choose a particular shop that requires a membership and a waiting time just to buy a loaf?

Besides MyIX, economists have warned that reinstating a policy that favors local shipping firms would make Malaysia appear ‘unfriendly’ to foreign investors. And Rais Hussin, the chairman of the Malaysia Digital Economy Corporation (MDEC), had implied that the effects are here already: three new submarine cables originally planned to land in Malaysia had been put under review, and so had foreign investments worth RM12-15 billion in data centers here.

Despite six ministries – MITI, Finance, Communications and Multimedia, Transport, EPU, MEDAC, and MOSTI – being instructed to study the impact of the cabotage policy and to come up with recommendations within two weeks back in April, it seems no decision had been made to address the issue so far.

This cabotage issue may just be a drop in the ocean when it comes to getting foreign investment, but with how hard we’re trying to get those right now, perhaps it would be worth the government’s time to stop, hold a real discussion with the stakeholders, and come up with a solution. With some effort, perhaps the situation can still be salvaged.

- 4.6KShares

- Facebook4.4K

- Twitter20

- LinkedIn18

- Email18

- WhatsApp99