We “know” that food naik harga during Raya… except it DOESN’T. Here’s the data.

- 109Shares

- Facebook84

- Twitter6

- LinkedIn6

- Email6

- WhatsApp7

Rejoice, Malaysians, for the festive season is upon us! Hari Raya is just around the corner, and besides visions of balik kampung and ketupats, this festive season (as well as other Malaysian celebrations) brings with it something less pleasant: rising prices of food items. Ever noticed that people always say that things naik harga during the festive season?

Like, chicken naik harga? CNY just round the corner. Beef naik harga? Ah, it’s close to Raya after all. Curry powder naik harga? Well… uh…

Anyways, it’s common to think that certain items will naik harga during festive seasons, but by how much, exactly? Since we had a lot of free time, we trued to find out whether the price difference is really that noticeable during festive seasons, and if it does, which festival is the most mahal. To do that…

We compared the gomen’s weekly prices of food items for three years

If this article is a journal, this is the procedure part, so just skip to the next header if technicalities bore you. Anyway, a government body called FAMA (short for Federal Agricultural Marketing Authority) have been monitoring the prices of certain agricultural products every week for the past 15 years, and they kept the weekly reports for those at this link (needs registering to access). Apparently, they have people going to markets every week and looking at how much certain things cost.

So if you want to know, say, how much a kilo of spinach sells for in Sabah on the third week of 2014 on average, just download the report for that week and you’ll find out:

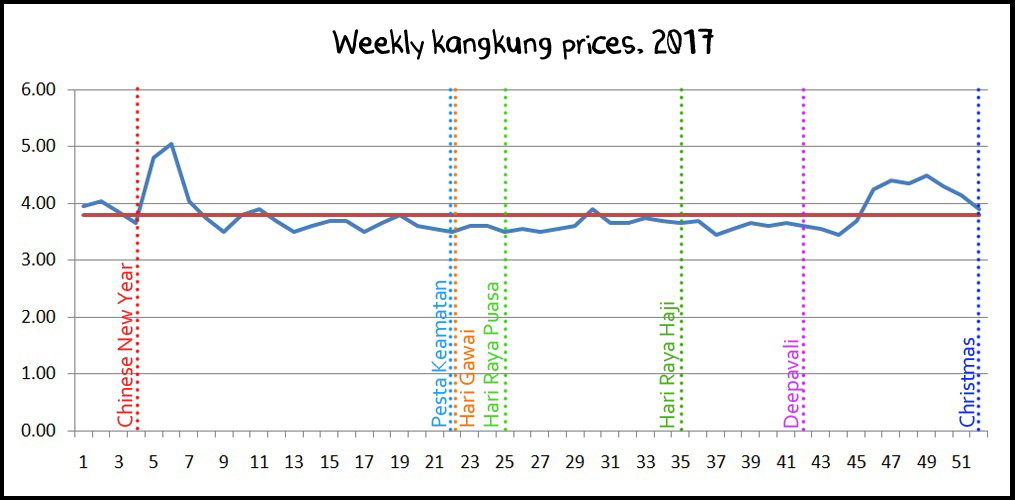

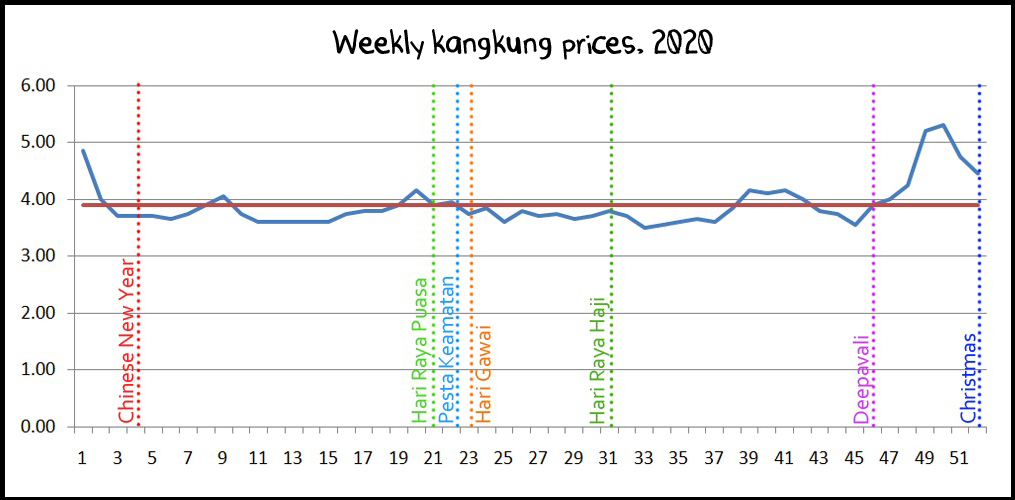

The reports for some weeks are missing, though: for example, there are no records for the rest of 2018 after GE15. So for this article, we picked three evenly-spaced years with all 52 weeks’ reports present – 2014, 2017 and 2020 – and extracted the average national prices for 10 items at consumer level. These items include things that we guessed would be affected by festivities, like live chicken, beef, and coconuts, as well as some random ones like kangkung and bendi for control.

After plotting out the weekly prices for these items in a graph against their average price for that year, we marked out seven festivities on each graph to see whether there’s an increase in prices around those times. Based on the Domestic Trade Ministry‘s list of festivities, we chose:

- Chinese New Year

- Hari Raya Puasa

- Hari Raya Haji

- Deepavali

- Pesta Keamatan

- Hari Gawai

- Christmas Day

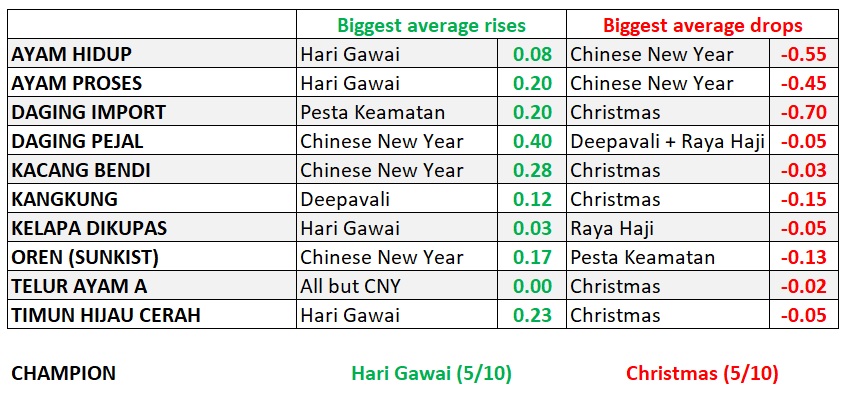

Alright. With all that settled, which festival wins this rumble? Drumroll, please. *trrrrrrrrrrr*

Perhaps surprisingly, we found out that in most cases…

The foods actually get cheaper during festival weeks

You can find our (very messy) datasheet here.

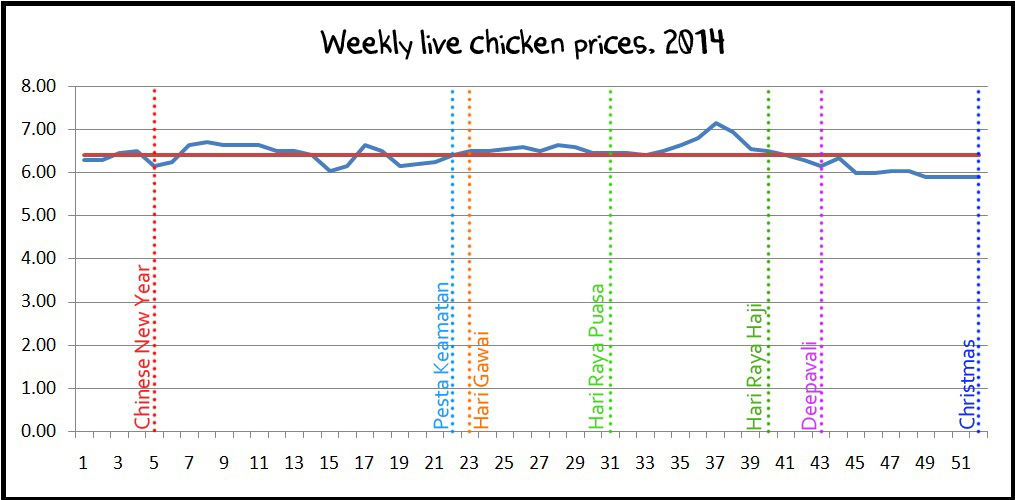

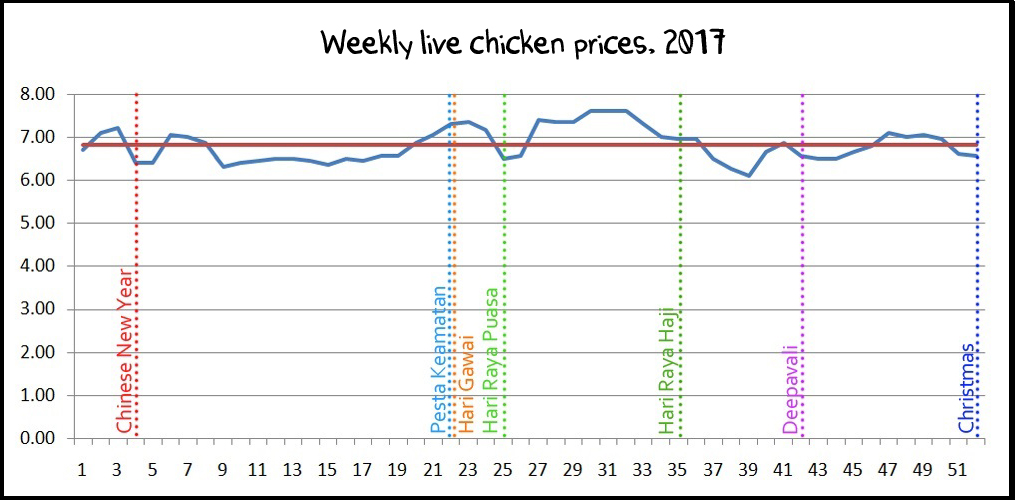

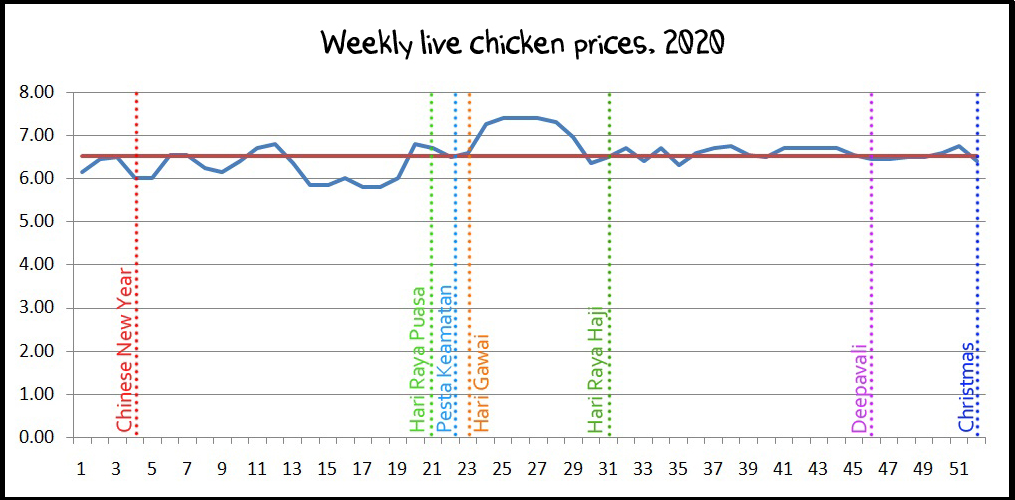

Honestly, when we started out on this, we thought we’d see things like meat prices shooting up for Hari Raya Haji or coconuts to go up during Deepavali (we’re dumb liddat), but the resulting graphs from FAMA’s data defied our expectations – they either drop during festive seasons, or don’t follow a clear pattern. For example, look at these graphs for live chicken prices for 2014, 2017 and 2018. Red lines show the average price for the year, and blue lines the weekly prices.

To answer the question in the title, CNY chicken is a bit cheaper than Hari Raya chicken. But for all three years, you can see a drop in prices for Chinese New Year, Hari Raya Puasa, and Deepavali. For other festivals, it depends on the year: sometimes goes up, sometimes goes down. In fact, the obvious peak in prices for all three years happened in the space between Hari Raya Puasa and Hari Raya Haji, and unless we’re sacrificing live chickens for Merdeka and Malaysia Day, it seems that these festivals don’t really cause drastic increases in prices.

An explanation for this might be because of the Domestic Trade Ministry’s price control schemes during festive seasons. These schemes prevent selected goods from being sold over a certain price around festive seasons. For example, for this year’s raya, price control is imposed on various chicken and beef products, eggs, and certain fish. Being caught selling these items above the price they set can get you steep penalties – up to RM100,000 fine and/or three years prison for individuals – so we’d be pretty dumb to set high prices when the FAMA people comes a-surveyin’.

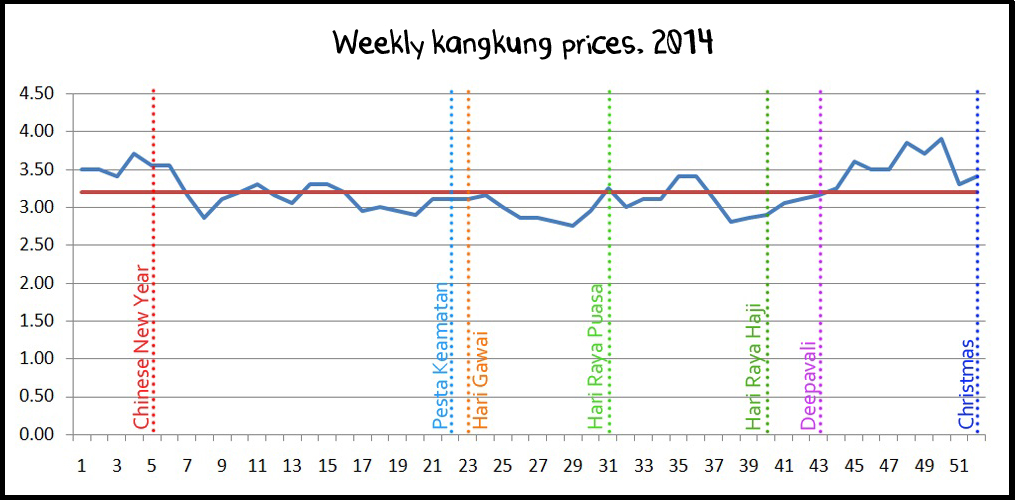

Prices for things that probably aren’t price-controlled also didn’t follow a specific pattern with regard to festivities. Don’t believe us? Here are graphs for kangkung.

You can see the rest of the graphs we made in this Google document, but in general, contrary to popular belief, the impact of festivities on the price of produce seems minimal at best. According to government data, that is. If there’s anything we learned today, it’s that…

Festivals don’t really cause food prices to spike

Just for fun (and because we’re a bit kiasu), we calculated by how much the price of each of the ten foods changed during each festivity on average, then found out which festival has the most change in prices. The winner is… Hari Gawai.

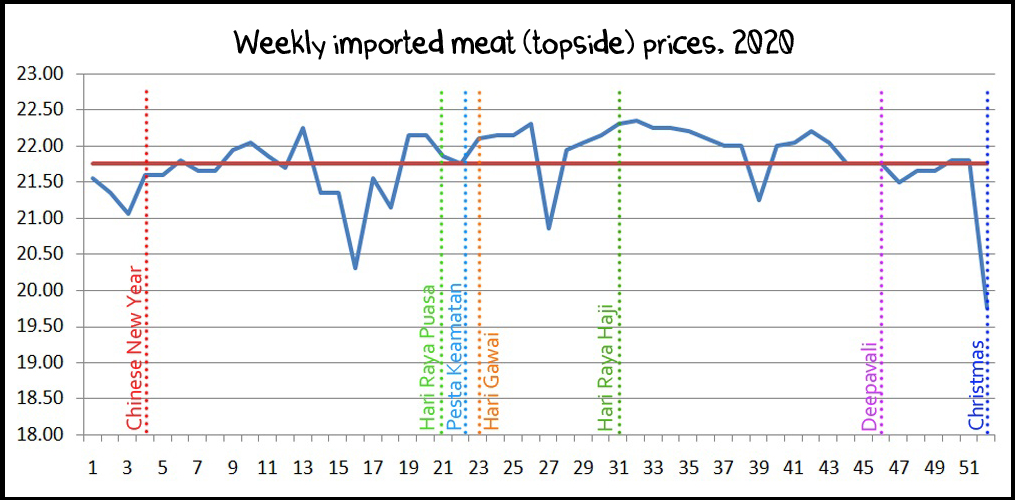

Even then, the highest price increase was for meat during CNY (40 cents’ rise on average), and it’s not very CNY-themed for that matter. So what gives? Well, when it comes to prices, it boils down to supply and demand, and festive seasons are just one of the many factors affecting that. For example, look at this graph for imported meat prices at the end of last year.

Just looking at the graph, one might infer that 2020’s Christmas caused the massive drop, but if you widen your scope, you’ll find that other developments at that time affected the price: besides Christmas, the last week of 2020 also featured a huge uproar about a cartel passing off imported kangaroo and horse meat as beef.

That’s an extreme example, by the way. If you read the FAMA reports we’ve pulled these data from, most of them have a commentary on why some items got more expensive/cheaper for the particular week. For example, in the third week of 2017, it was reported that frequent rains in Perak that week destroyed some crops and affected the harvest process, leading to a reduced supply for some vegetables, causing an increased price all the way from the farm to the markets.

Still, the graphs we made were from official data. We didn’t actually have the intern go down to the markets to check prices every week, so there’s a chance that published data may be different from actual data. So maybe the prices do go up every festive, but we’re going to need a lot more interns to confirm that.

- 109Shares

- Facebook84

- Twitter6

- LinkedIn6

- Email6

- WhatsApp7