In 1915, British Malaya lost Singapore to a mutiny. So they got help from… the Japanese

- 1.4KShares

- Facebook1.4K

- Twitter12

- LinkedIn10

- Email16

- WhatsApp30

When you think of Malaya in World War 1, you probably wouldn’t think it was a major part of our history. After all, most of the war was fought in Europe, and Southeast Asia was largely peaceful.

But what if we told you that in the year 1915, Britain actually lost control of Singapore (which was then part of Malaya) and Japan’s rising sun flag was raised over Singapore for the first time – wayyyyy before World War 2?

Okaylah, Singapore wasn’t invaded by the Japanese this time. Instead, the Japanese were actually helping the British regain control of Singapore after a British regiment started a mutiny.

……and it was all because of ze Germans (of course)

In 1913, a bunch of Sikh Indians founded the Ghadar Party – in California of all places – with the goal of overthrowing the Brits in India. Fun Fact: Ghadar means ‘mutiny’, so it should have been pretty obvious what they were trying to do. Surprisingly enough, they actually got a pretty large following as they attracted Indians from all over the world to their cause.

And eventually, they also attracted the attention of the Germans.

So in case you didn’t know, WW1 also saw the Germans going up against the Brits. One of the plans the Germans had at the time was to sway Muslim support over to their side. In fact, Dudley Ridout, the garrison commander in Singapore (the big boss of the soldiers), noted in a report to his boss that German prisoners of war in the Tanglin barracks – an internment camp for Germans in Singapore – would pretend to pray and recite the Quran to convince their guards they were Muslims too.

This, plus the German alliance with the Ottoman Empire, helped Germany position itself as an ally of Muslims around the world.

Seeing an opportunity to cause problems for the British, the Germans approached the Ghadar Party and offered them a whole bunch of money. With German funding, the Ghadar Party started a newspaper called (what else) Ghadar and distributed it around the world. The Germans wanted to use the ‘Ghadar’ to spread anti-British propaganda to Muslims within the British Empire, expecting it to result in revolt within the colonies. So as you might expect, these newspapers would make their way to Colonial Malaya as well.

In other words, if you ever get annoyed by sponsored content on sites like Cilisos, you can blame the Germans for starting it first.

The Ghadar somehow reached its most unexpected target audience in Singapore

Singapore was an important world city, and at the time borders were very porous (Passports weren’t a big thing yet). This openness allowed the underworlds of other global cities in Asia to hook up with Singapore.

Like any other British colony at the time, troops were imported to help defend Singapore and one of them was the ‘5th Light Infantry’. Formed in British India, they were primarily Muslim soldiers instead of the Hindus and Skihs that the British preferred to recruit at the time. And because they stayed loyal and helped the Brits fight off the Indian Rebellion of 1857, they were nicknamed the ‘loyal 5th’.

If you can’t already see it coming, this nickname will soon become pretty ironic.

Perhaps due to Singapore’s openness at the time, the Loyal 5th were exposed to information that wasn’t exactly full of praise for the British, with news coming from places as far as India, Canada, US, UK, Germany, and Turkey. Not just that, the Ghadar newspaper was smuggled in through Sikh Gurdwaras in Singapore, which became an important node for the Ghadar party to spread its ideas to other parts of Asia.

In fact, Radical Ghadarites passed through Singapore and Penang to travel back to India, to attempt a mutiny later in 1915.

One of these radicals (who was apparently left behind to raise funds) was preacher Nur Alam Shah, who was the Imam at the Kampung Java Mosque in Singapore. Sepoys from the Loyal 5th and Malay States Guides (an Indian regiment formed in Malaya) would pray together there, and Nur Alam Shah would spread anti-British sentiment, promising the arrival of German warships to overthrow British rule in Singapore.

Another guy called Kasim Mansur owned a kopitiam and would often invite sepoys to lepak with him (to complain and plot against British rule too). He was arrested when he was caught sending a letter to the Turkish consul asking for them to send a warship to Singapore, claiming that the Malay States Guides stationed there were ready to mutiny (Which is probably why the British sent them back to Taiping). He was later arrested and executed for sedition.

So, while the Ghadar Party was unable to sway the locals of British Malaya to their cause, they succeeded in reaching the one group that actually had weapons and training…

So the ‘Loyal 5th’ mutinied against the British

The Brits actually caught on that their ‘Loyal 5th’ was having their loyalty tested by Ghadar influence and thought it was a better idea to send them to garrison Hong Kong instead.

But by this time, it’s probably not a surprise that their trust in the British was pretty bad. There were rumors that Hong Kong was just an excuse, and they were actually being sent to the battlefields of World War 1 or, worse, that the Brits were going to drown them at sea.

This was the spark that kicked off the mutiny 2 weeks later.

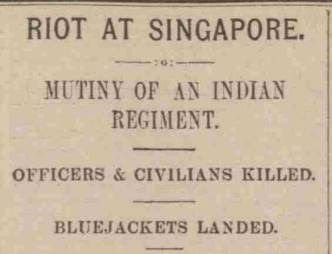

Monday, 15 February 1915, was day 2 of CNY. Much like how it’s like today, it was also a day of rest and celebration in Singapore back then. Well, except for the Loyal 5th, who were tasked to load a truck of ammunition.

So what happens when you put a bunch of unhappy soldiers in contact with a lot of bullets?

At 3:00 pm, a shot was fired, and the truck was raided by mutinying sepoys. At this point, half of the regiment was in mutiny, while the other half that didn’t join in ran off to the jungle and surrendered later.

The city was caught completely off-guard by the mutiny – the military officers were lazing around and in fact, Colonel Martin, the commanding officer was sleeping in his house when the mutiny happened.

During the commotion, the mutineers split into 3 groups:

Group 1

Went straight for the German internment camp to recruit the Germans to their cause. However, most of the Germans chose not to join them.

Group 2

Went to the centre of town, killing civilians, police officers and soldiers along the way.

Group 3

Went to recruit more mutineers at the barracks of the Malay States Guides. After some joined them, they went to kill Colonel Martin at his house but were unsuccessful.

Probably the best part of this story is that the CNY holiday mood was so strong that Colonel Martin even forgot to notify the police when he was awoken…. not that it would have helped much.

In the police force, only the Sikh police officers were trained to use arms, and they weren’t trained to deal with armed soldiers. The King’s own regiment, the Yorkshire Light Infantry, that was supposed to garrison Singapore was sent to fight in World War 1 and, since it was CNY, the Chinese volunteers in the Singapore Volunteer Force were not available.

In other words, the only armed military force that could have defended Singapore against a mutiny by the Loyal 5th was…. the Loyal 5th.

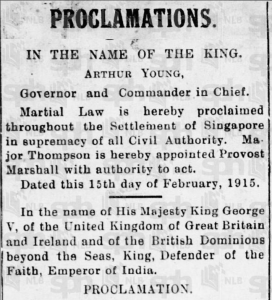

So the British had no choice but to send out an S.O.S.

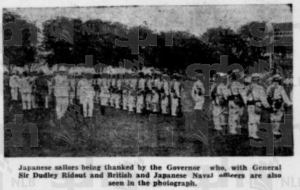

Even though they’d enacted Martial Law at this point, the British were only able to muster up about 200 armed constables from the local population, which wasn’t enough. So, Britain had to call for help form passing sailors, and they gathered an impromptu force of British, French, Russian and Japanese sailors, with the Japanese consul summoning another 190 Japanese civilians to help.

Long story short, by their powers combined, the mutiny was quickly countered. Some of the mutineers tried to escape into Johor but were hunted down by the Sultan of Johor’s army. In the end, about 200 mutineers were charged, and the British then held public executions for months after that.

So, as a thank you to the Japanese for quashing their little mutiny problem, the British flew the flag of the Empire of Japan above Singapore. But before you go around telling everyone about this flag thing, we should probably mention that this came from the Japanese side of the story. The British never mentioned flying the Japanese flag so take this with a grain of MSG la.

However, the one indisputable time the Japanese flag flew above Singapore was when it fell to the Japanese in World War 2, on February 15 1942…. exactly 27 years after the mutiny.

So how did this mutiny change British Malaya?

Although you will never see this in any sejarah textbook, it affected Colonial Malaya in interesting ways. Sho Kuwajima, a Japanese historian, actually called this incident the “turning point in the history of Asia”. For starters,

Spying was made cool.

- The British focused on counterespionage, gathering intel, and monitoring political dissidents.

- They employed secret agents in Malaya, Singapore, and even as far as China and Canada.

No more visa-free travel.

- International travel was subject to more regulations, and porous borders were sealed and controlled. The government could then effectively exile people by tracking people’s life histories and even the scars on their bodies.

- Britain started expelling political undesirables on a larger scale, eventually deporting 20,000 people from Malaya between 1911 and 1931.

Singapore became super kiasu.

- In August 1915, the British implemented a “Reserve Force and Civil Guard Ordinance” (compulsory military service), which eventually became Singapore’s National Service law.

- The political intelligence bureau was set up to do spy stuff, and became the present-day Internal Security Department.

It (may have) inspired Tok Janggut to start the Kelantan Rebellion.

- The people in Kelantan believed that the British were losing power and the Singapore mutiny became ‘proof’ of that.

- This ‘proof’ is said to have given Tok Janggut and his supported additional encouragement to go ahead with the rebellion.

“[The] Kelantan people have for some months past undoubtedly believed that Great Britain had faced defeat in the European war. Therefore when the Singapore mutiny broke out in February, wild stories spread through Kelantan of the massacre of Europeans and the successes of the mutineers. … So firmly did the Kelantan Malays believe in British impotence in the Straits Settlements that, when the British men-of-war were on their way to Kelantan, the news was received with incredibility even in the highest circles.” – excerpt from a report by William Maxwell, acting colonial secretary, to the government of the Straits Settlements

- 1.4KShares

- Facebook1.4K

- Twitter12

- LinkedIn10

- Email16

- WhatsApp30