In 1918, a pandemic killed at least 40,000 in British Malaya. Here’s what happened.

- 10.6KShares

- Facebook10.1K

- Twitter43

- LinkedIn47

- Email49

- WhatsApp360

[If you enjoyed this story and want more, please subscribe to our HARI INI DALAM SEJARAH Facebook group]

[Note: This article was originally published on 19 March 2020, back when we were still optimistic. Rewriting it would be a pain, so we edited parts of the article to reflect the current situation where necessary.]

Chances are, you’re already very aware of how serious the coronavirus situation in Malaysia is right now. Before seeing this article on your feed, you’ve probably scrolled past stuff like Malaysians panic-buying groceries, panic-coming-up with policies, panic-not-getting-invited to a health meeting, panic-lining-up at police stations to get permission to balik kampung, or panic-gathering at bus terminals for the same reason.

It’s not hard to see why people are getting jittery over the whole thing. A few days before the time of writing, the number of confirmed cases have been growing faster than your investments, and 2 people have already died. [Update: as of 12 July 2021, the death toll had climbed to 6,158]

Taking a page out of history, roughly 100 years ago the world was hit by an especially deadly disease known popularly as the Spanish flu. To give an idea of how deadly it was, it killed more people in 24 weeks than HIV/AIDS did in 24 years. It infected people all over the world, being estimated to have reduced the world’s population by between 1-6%. As for its impact on Malaya at the time…

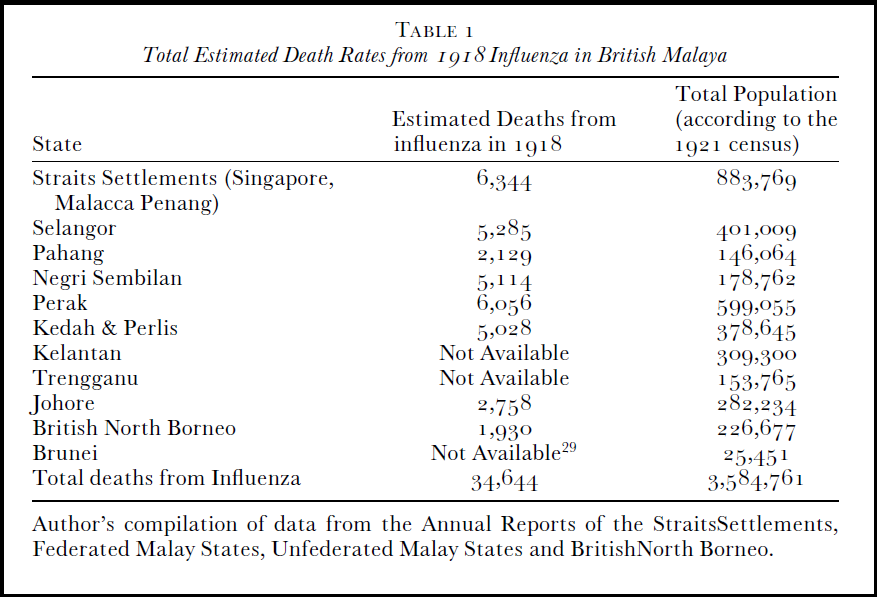

The Spanish flu killed off 1% of Malayans and North Borneans in 1918

[Disclaimer: Our main reference for this article is Liew KAI Khiun’s paper titled “Terribly Severe Though Mercifully Short: The Episode of the 1918 Influenza in British Malaya“, which compiled the scarce mentions of the 1918 pandemic in Malaya and Borneo’s literature from back then. This article is a simplified version of the events depicted in that article, so if you want to know more about this flu in Malaya, you should totes check it out.]

1% may not seem like much at first glance, but for 1918 Malaya and North Borneo, that’s about 40,000 people. It’s hard to put that into perspective, but if you’ve seen the movie Titanic, 1,500 people were estimated to have died in that disaster. The Spanish flu casualties in Malaya then equals to roughly 27 Titanics. While it’s just an estimate (the number may be higher or lower depending on unreported cases), it’s not hard to believe if you read the excerpts of news reports from back then.

According to a correspondence,

“It was really pathetic to see member after member of the same family being carried out of the house within a short interval of each other. A Malay in Kuda Prye buried a child one day another the next day, another and was himself buried. In many cases, after burying a mother, the funeral party would return home to take away the child and wife.” – exceprt from a correspondence, taken from Liew Kai Khiun’s paper.

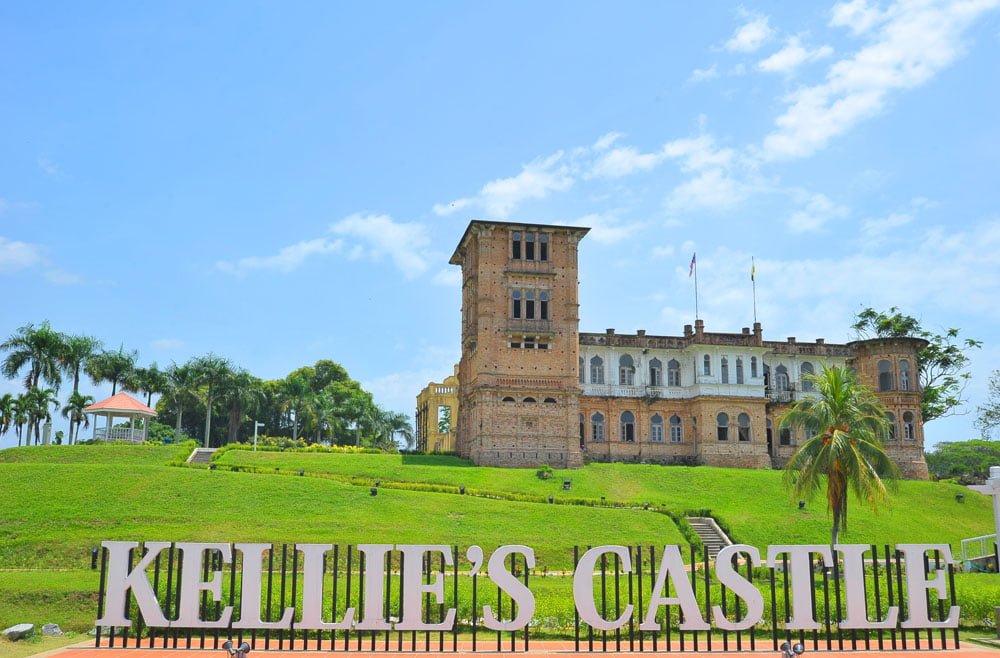

Based on statistics at that time as well, it would seem that the hardest hit community had been the Indian laborers, whose deaths in Perak during the influenza period is roughly double (372 out of 1,000) that of the Malays (129.6/1,000) and the Chinese (158.4/1,000). This was reflected in the process of the building of Kellie’s Castle in Perak, which according to stories, was believed to be cursed because 70 of the Indian workers who worked on it died from the flu.

While the disease was reported to have affected people in all states of Malaya and North Borneo, perhaps the most famous person to succumb to that disease then was Sultan Abdul Jalil, the 29th monarch of Perak who, after a short reign of about two years, succumbed to the flu and passed on in October 1918. So you can see how widespread and deadly the flu was, but…

How did the Spanish flu get into Malaysia, anyway?

Before the recent coronavirus was re-named as Covid-19, it was called the Wuhan virus, so one might think that it got into Malaysia by someone from Wuhan, China. However, that probably wasn’t the case with the Spanish flu. The breakout happened during World War I, and as the story goes, reports about the pandemic was censored in warring countries to maintain the morale of their troops.

Spain, on the other hand, was not involved in the war, so their newspapers freely reported on the pandemic, giving the impression that they’re hit harder by the flu than other countries, hence the ‘Spanish flu’ nickname. But if it’s not from Spain, then where? Well, no one knows for sure, but theories have ranged from the United States, northern China, or a British army base in France.

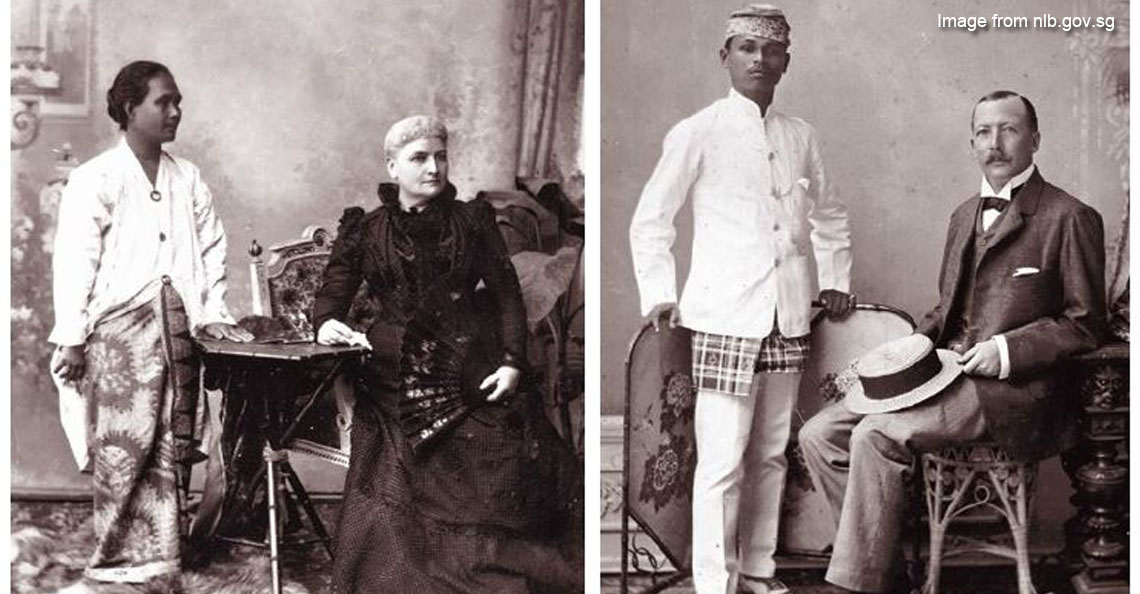

Regardless of where it came from, it got so widespread that it even reached the Arctic regions. Given the ongoing war and Malaya’s situation as a British colony at the time, people were bound to come and go, and with the flu being so widespread it was inevitable for Malaya to be affected. While we don’t know how exactly how it got into Malaya, it was commonly believed to have started from the principal port of Singapore, then spread to the rest of the region.

Based on accounts, it would seem that the disease probably spread through maritime routes from passengers and migrant workers from the South China Sea, and later on through land routes when they moved from the ports to further inland. And while there had been warnings about the flu outbreak from the British government in Africa to Singapore, it didn’t do much.

Things progressed rather shockingly fast after that. For example, during the second wave of the outbreak in October, the local media had at first been convinced that the flu outbreak in the East ‘does not assume so serious a character as it does in the West’, but that stance changed dramatically just one week later.

“The present epidemic of influenza is one of the worst that has occurred. It has finally broken through hygienic precautions and taken the fullest advantage of the deplorable neglect of the native population of Singapore, Penang and the Federated Malay States.” – media excerpt, taken from Liew Kai Khiun’s paper.

As for how it got to that point…

It would seem that people didn’t know much about the flu then

Today, we know that the Spanish flu is caused by the influenza virus H1N1, the improved version of which caused the 2009 swine flu pandemic. We also know now how much of a havoc it can wreak, how to identify the symptoms, and how to stop it from spreading. It wasn’t that way back then.

For example, a public health report from 1918 Penang did report a sudden outbreak of a fever ‘of unknown origin’ when the pandemic first started in July. However, it wasn’t until the second wave in October that this fever was recognized as an influenza, with the distinguishing feature identified as constant, often serious pulmonary complications.

It may have been too late by then. The daily average number of deaths (from all causes) doubled within a few days, and by the end of October, it was six times higher. The flu didn’t just take Penang by surprise. The influenza pandemic was a new thing for most of the world, and it defies what people already knew of infectious diseases back then. As a 1919 report by the Sanitary Commissioner with the government of India had put it,

“There is no specific cure or certain preventive [actions] for influenza and when it spreads with the alarming rapidity to which reference has been made, medical science can do but little to check its incidence.” – the report excerpt, taken from Liew Kai Khiun’s paper.

While the British in Malaya had established measures against infectious diseases since the 1870s, like early detection at ports and quarantine camps, influenza wasn’t on the list of diseases to look out for back then. And due to the new nature of the disease, it took some time before people became aware of the flu. According to a Chinese community participant, many of them thought that it was just another malarial outbreak, so they didn’t take the correct precautions.

Also due to the newness of the disease, the authorities were undecided on what to do exactly, resulting in conflicting recommendations. In the absence of a clear policy, the state health authorities took action on their own and started basic measures, like house-to-house inspections, distributing disinfectants to the public, closing down schools, cinemas and theaters, and asking sick people to stay in bed until the symptoms are gone.

Still, it would seem that despite all the death and sickness around, people seemingly weren’t scared of public gatherings. Although there were health warnings against large public gatherings, Sultan Abdul Jalil’s funeral in October 1918 was reportedly well-attended, and thousands poured out to the streets to celebrate the end of WWI in November. However, there was also a mention of plantation owners holding a conference to postpone Deepavali celebrations until the flu passed over, so perhaps some caution was exercized.

Regardless of that, knowing what we do now about what happened in 1918 Malaya, one might wonder…

Will the current coronavirus pandemic be that bad?

[Update Jul 2021: Please remember again that we wrote this way back last year 😓]

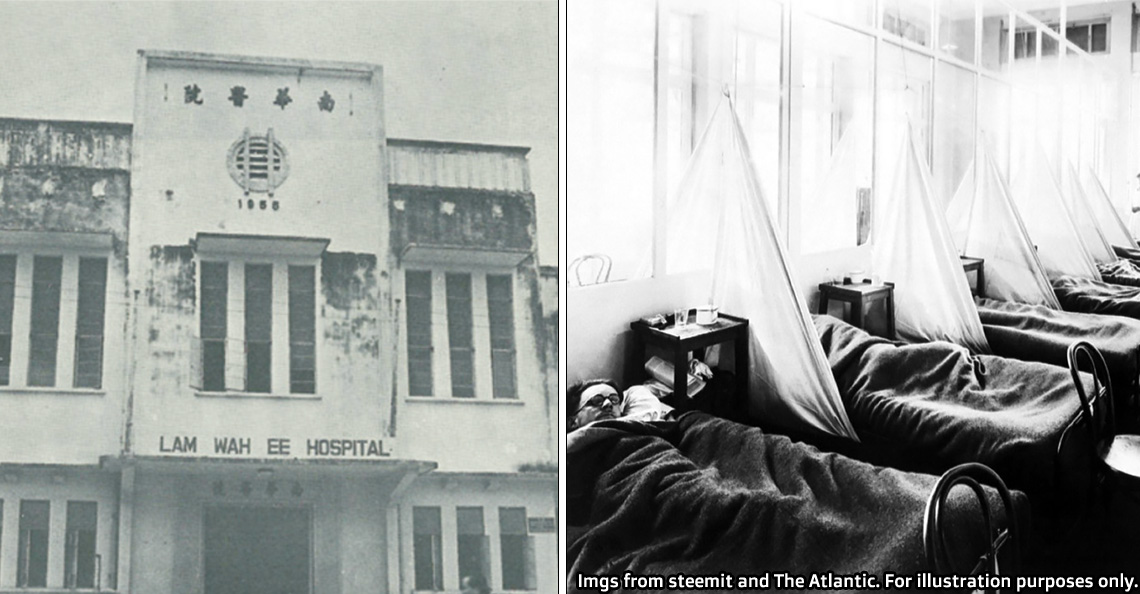

It’s hard to say for sure, but the circumstances between now and 100 years ago are different. The Spanish flu hit the world during a time of war, and sick, malnourished people are easy pickings for the new virus. The pandemic also kinda kickstarted the building of better health facilities and networks to handle infectious diseases in Malaya starting 1920, and since then we’ve improved considerably.

While we are better prepared for pandemics, there are some similarities between the current pandemic and the one from 100 years ago, like the sudden escalation of things and some people not taking it seriously at first, to name a few. Also, we didn’t mention this in this article, but there were also efforts by the community to help each other out during the crisis, which we we are also starting to see right now.

Regardless of good or bad ones, let’s hope that the similarities stop there. We probably don’t want the hospitals to be so overcrowded like in 1918 Pahang, where sick people had to be turned away and the hospital is so short staffed that their gardeners and coolies have to be pressed into service as attendants. And while we’re already starting to see deaths, we probably don’t want the number to go any higher, either.

[Update Jul 2021: Oh if only we knew]

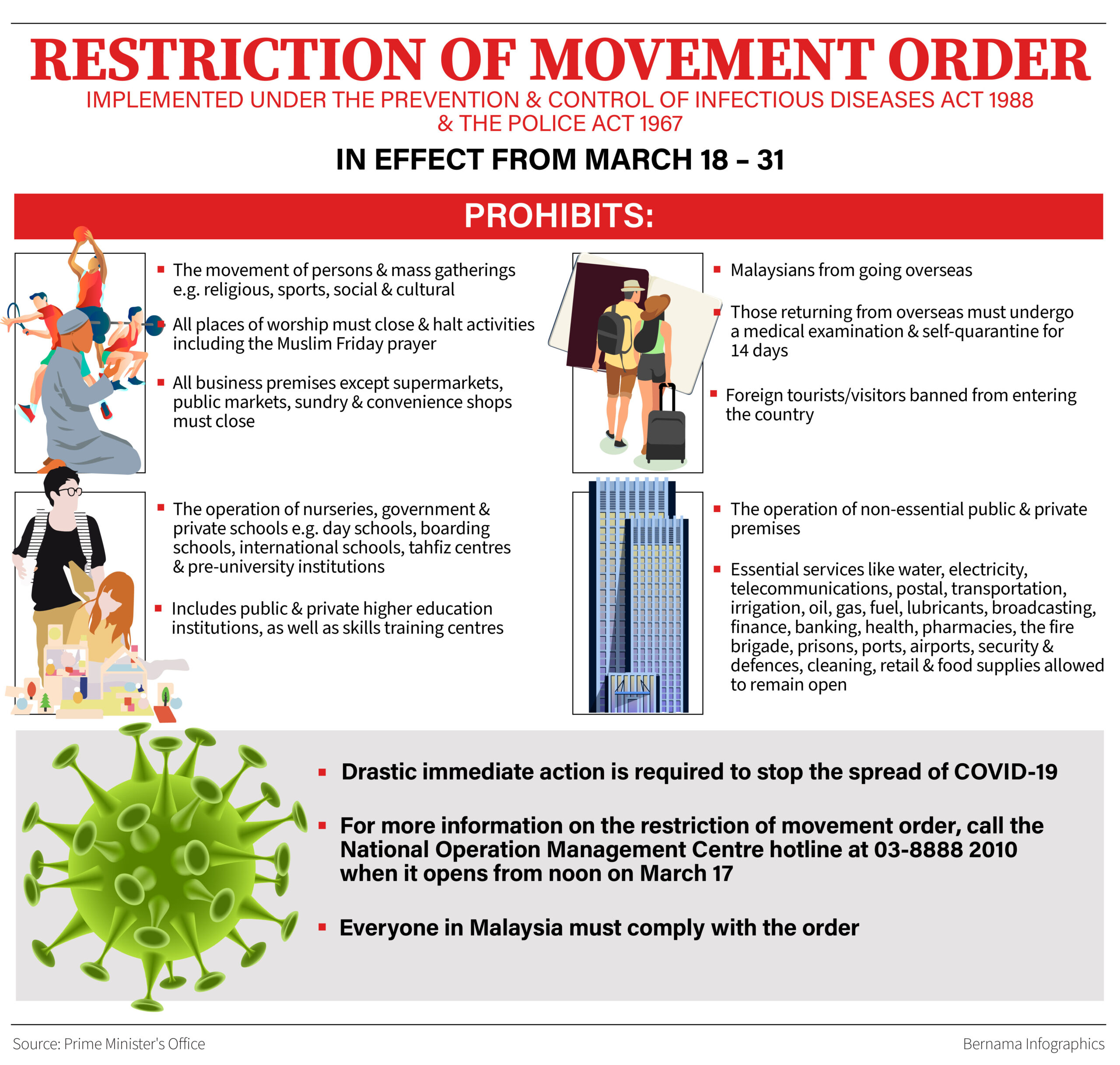

In light of recent events, the government have implemented the movement control order, and it is hoped that the order will manage to slow down the spread of the coronavirus, or even stop it completely. But it would only work if we band together and just… stay put, as advised by Prime Minister Muhyiddin Yassin.

“…I would like to appeal to you, please, stay put where you are. If you have plans to return to your hometown, cancel them. Go back another time. I ask for your help for just the two weeks.

“The government hopes that after two weeks, those with symptoms can be isolated for treatment and Malaysia can be free from Covid-19,” – Muhyiddin Yassin, as reported by Malaysiakini.

It’s not that hard for most people, and if everyone complies, hopefully we can go back to work in two weeks’ time. [Last update Jul 2021: We didn’t 😔]

[If you enjoyed this story and want more, please subscribe to our HARI INI DALAM SEJARAH Facebook group]

- 10.6KShares

- Facebook10.1K

- Twitter43

- LinkedIn47

- Email49

- WhatsApp360