Malaysia has one stop crisis centers for rape victims, and it’s one of the world’s best

- 2.2KShares

- Facebook2.1K

- Twitter15

- LinkedIn13

- Email9

- WhatsApp32

Last year, CILISOS managed to meet South African-born Claire McFarlane, who survived a brutal rape attack while living in Paris in 1999.

After being assaulted, she got to a hospital, where things didn’t improve:

“I was then left in the hospital corridor with people walking past, looking at me, questioning me for 5 hours… The doctor who came along looked just like my attacker and was a really aggressive man. Not kind or caring in any way. Made me recap my story again like 5 times.

I was desperate for a toilet. It had been quite a few hours since the attack. I was told that I couldn’t go to the toilet until they did the rape kit. But they weren’t gonna do that first.” – Claire told CILISOS

After her ordeal in the hospital, which included being victim-blamed for the attack, she spent 16 years fighting the case in France. Following that, she started the organisation Footsteps To Inspire, through which she conducts 16km beach runs in every country to help raise awareness of sexual violence.

Her advocacy has connected her to many people and events worldwide, including the event where we met her. It was during this conversation when she surprised us by claiming that Malaysia is one of the best countries in helping victims of sexual, physical and/or emotional abuse, in the form of one stop crisis centres (OSCC).

Now this was the first time we’ve actually heard of the OSCC, so we spoke to a few industry insiders to learn more about Malaysia’s OSCC system. And as it turns out…

Victims can find all the help they need in any major public hospital

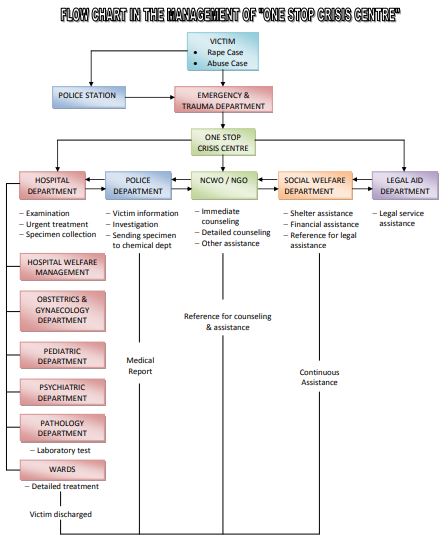

The OSCC is an integrated multi-agency service in the emergency departments of most major public hospitals to help the victims of violence in one location. Because the OSCC deals with victims that have been thru a lot, OSCC’s standard operating procedures consist of a comprehensive approach consisting of medical, psychological, social, shelter and legal support.

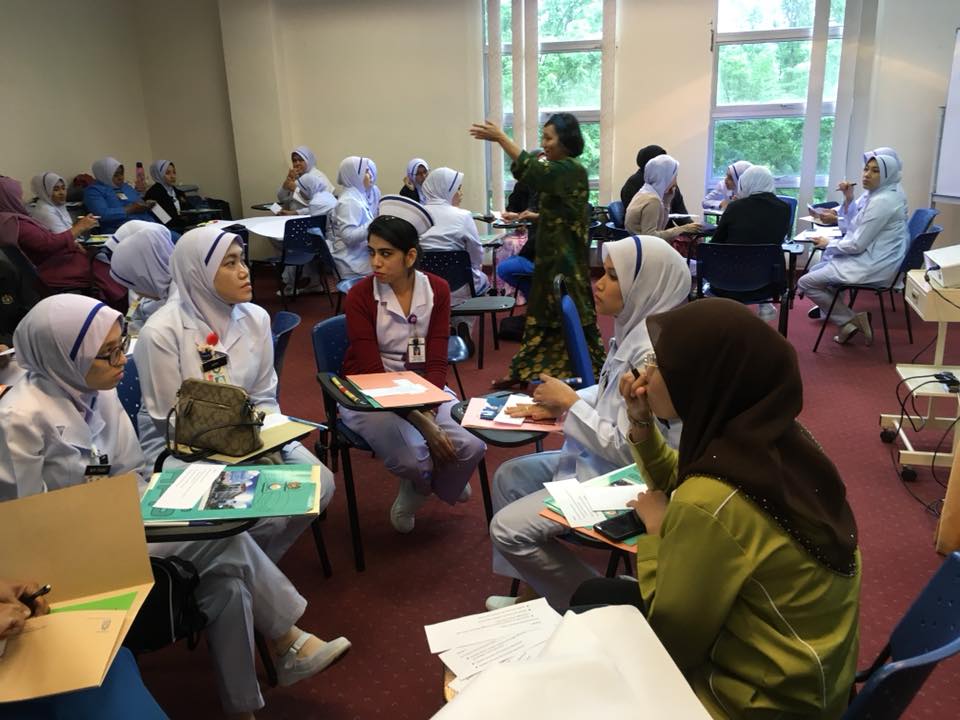

To further understand how OSCCs work, we spoke to Dr Chandra Kumari of the UMMC Emergency Dept. According to her, victims are admitted through the emergency department’s triage counter, where a health care worker assesses the victim’s clinical severity. The victim is then moved to the OSCC area for medical assessments by the emergency department, before being referred to other specialists such as pediatrics, O&G, geriatrics, surgery and psychiatry for treatment.

A medical social worker will also assess the victim to decide the safe placement of the victim if necessary. If the victim is below 18 years old, a child protection team known as the SCAN (Suspected Child Abuse and Neglect) team will assess the case. Other stuff such as taking samples of blood and evidence of injuries and assault will also be taken from the victim in the event a police report needs to be made.

Of course, we’re simplifying quite a bit of the whole procedure, but you can click here to check out the full OSCC Policy and Guidelines that all Ministry of Health (MOH) hospitals have to follow. This includes all the stuff that Claire praised for creating a safe space for the victims and not requiring them to repeat their case over and over again – And she’s apparently not the only one applauding the OSCC approach.

Japan’s Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare’s report on Malaysia’s healthcare system apparently stated that having an avenue where all help is available for the victim spares them the trouble of not knowing where to go to. This minimises the stress and trauma the victim may have, and is the main factor behind the launch of the OSCC back in 1996.

Turns out Malaysia might be leading the way in violence response

Although University Hospital (now UMMC) started services for the adult sexual assault cases in 1979, a more structured approach started in the mid-90s when the first OSCC was established in Hospital Kuala Lumpur (HKL) by the former Head of Emergency Department, Dato Seri Abu Hassan Asaari, who realised that victims had to go to multiple places to get the help they needed.

“For example, a survivor will need to go to the police station for a police report and then come to the hospital for a medical check up and later will have to go to social welfare for social support and shelter.” – said Dr Nor Khatijah Ahmad of Hospital Selayang’s Emergency Department.

Being among the first countries in this region to adopt the Domestic Violence Act of 1994, Malaysia could adopt a large-scale model for violence response, which could be followed by other Southeast Asian countries. In fact, Claire added that even European countries don’t have similar OSCCs.

“Europe is many years behind Malaysia on this. Currently, the countries where I’ve encountered a one-stop crisis centre is Sweden with just one and Belgium with a prototype. Though the service is not as diverse and complete as the one I saw in Malaysia.” – Claire

Dr Chandra shared that, in 2018, a total of 308 cases were registered in UMMC’s OSCC, out of which there were 124 domestic violence cases, 136 SCAN (Suspected Child Abuse and Negligence) cases and 48 INSAN (adult sexual assault) cases. And it’s not just females who’ve seeked help from OSCCs; both females and males have sought help in the OSCCs, with most of the male abuse cases being physical abuse.

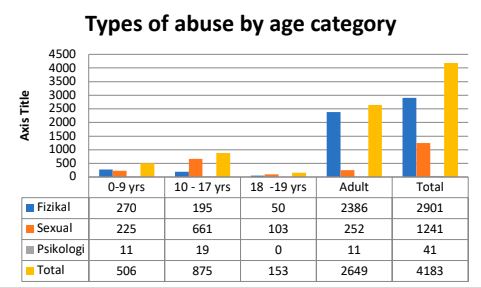

For the whole country, Dr Noor Hisham, the director-general of MOH, shared that there are a total of 4,183 cases in 2017, with psychological abuse being the smallest part of the reported cases while the rest of the cases are physical and sexual abuse. Adult victims make up the majority of physical abuse cases while youngsters aged 10-17 years make the highest proportion of sexual abuse cases.

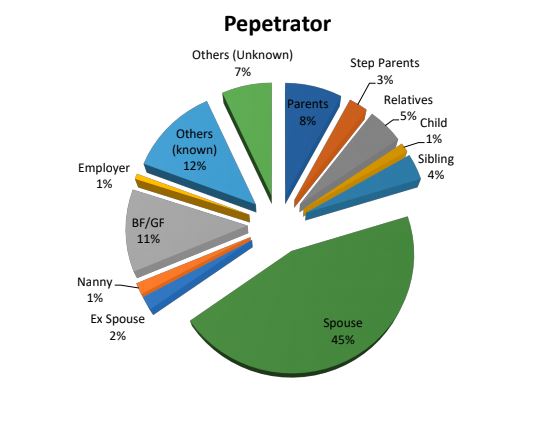

The really sad part about the stats is that the people who abused the victims are supposedly their loved ones, with spouses taking up the biggest slice of the abuser pie at 45%!

But these are just the cases of victims who mustered up the courage to come forward and seek help from the OSCCs. When Batu Kawan MP Kasthuri Patto shared stats on sex crimes and domestic violence last year, she said something that would make one question the stats:

“These are only the reported cases… what about the ones which have not been recorded or reported?” – Kasthuri Patto asked.

Turns out unreported crimes can be a difficult thing to address, which is why…

Malaysia still has more ground to cover

Despite having a really good OSCC system in place, our country still bears many challenges in violence response, which can come from every side of the service, whether it’s the victim, society or even the system itself. Victims can get pretty hesitant about coming forward for help, not just from the fear of getting attacked by their attackers, but also from the social stigma and possibly any religious constraints of being a victim of violence.

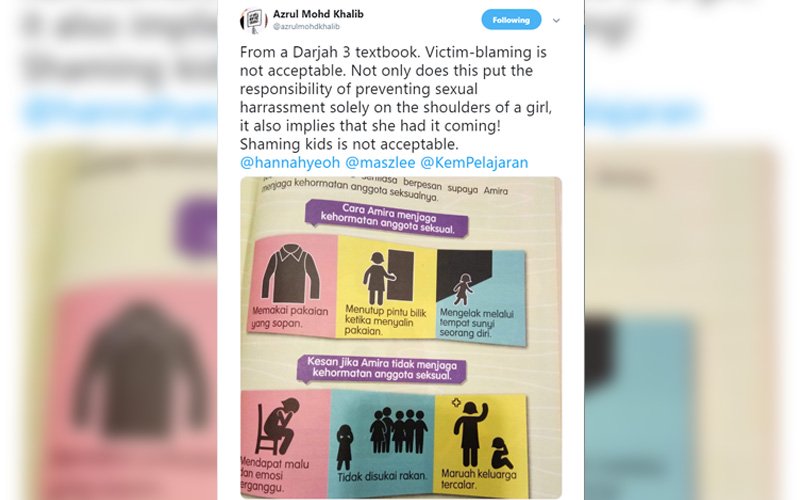

Similar to Claire’s experience with the French healthcare and judiciary system, Malaysian society, even those close to the victims, might not be supportive and empathetic, and instead resort to victim-blaming and shaming. This is usually a result of a lack of awareness on the issue. For the victims, it’s likely a lack of awareness on their individual rights and children’s rights.

The challenge can also arise from the system and agencies, such as difficulties in making a police report due to paperwork and red tape. And even if the police reports were made smoothly, the constraints don’t stop there. Dr Noor Hisham told us that not all hospitals have the necessary space and resources to provide social and shelter support.

This is especially true in rural areas… Although this service is available in all MOH hospitals and that all staff stationed in rural clinics and Klinik Kesihatan are informed about it, some hospitals are not equipped with exclusively designated OSCC examination rooms and face obstacles in maintaining a chain of evidence due to limited lab facilities.

Another thing that really defeats the purpose of an OSCC as a ‘one-stop’ place to seek help is that cases from certain hospitals without the relevant specialties are transferred to the nearest specialist hospital for further management. To top it all off, as we said earlier, the probable lack of awareness, stigma and the culture of shame and blame is deeply rooted in our society, especially in rural areas.

That’s why Dr Khatijah thinks that the OSCC system still has more work to do in terms of exposure and collabs, while Dr Chandra also hopes that the police reporting process will be hastened. Luckily, there are plans to address these limitations.

Apart from the awareness campaigns that have been carried out in the past via road shows, social media and schools, Dr Noor Hisham said that MOH will be giving continuous training and awareness programs to the healthcare staff in district hospitals and government clinics.

To make sure the OSCC cases are managed swiftly, professionally and safely, the training programs will focus on strengthening the multidisciplinary approach within MOH and interdepartmental collabs with PDRM, JKM and so on. Dr Noor Hisham also mentioned MOH’s plans to include acute psychological crisis intervention (click here for fact sheet) and include elderly abuse and neglect in the scope of OSCC as Malaysia becomes an ageing nation by 2030.

With all these plans under way, there’s hope that the OSCC is managed optimally and improved to be its best possible version. Because in the end:

“We all have one goal, that is, to help the survivors get back on their feet.” – Dr Khatijah.

- 2.2KShares

- Facebook2.1K

- Twitter15

- LinkedIn13

- Email9

- WhatsApp32