[UPDATED] The tiny May 13 cemetery most Malaysians never knew about

- 14.5KShares

- Facebook13.0K

- Twitter137

- LinkedIn136

- Email209

- WhatsApp916

[This article was originally published in 2018.]

[UPDATE 23 NOV 2024: The cemetery is no longer in immediate danger of being turned into a carpark. According to the Persatuan Sahabat Warisan Kuala Lumpur dan Selangor (Pesawa), the Gombak Land and District office had notified them that the site had been officially gazetted as a non-Muslim cemetery, and that they had been appointed as the managing agent.

“The recognition of the May 13 Cemetery as an official non-Muslim burial site is the result of years of effort by all our members and the fulfilment of a long-standing hope of the public. This designation finally allows everyone to lay their concerns to rest,” – statement by Pesawa, as reported by MalaysiaKini.

END OF UPDATE]

If you’ve ever been to the hill behind the Jamek Ibnu Sina mosque and the Sungai Buloh Hospital, you might have stumbled upon a rundown cemetery that not many people know about. In a small space the size of nearly two badminton courts, it has more than 100 headstones packed together, arranged in four rows.

Covered by weeds and in bad shape, most of the headstones were simple with just names and dates.

Some did not even have a name at all.

But the one thing they all had in common was that these headstones were ‘by the courtesy of the Malaysian government’.

For more than four decades, not everyone knew that this cemetery even existed. Then in 2017, it was reported that the cemetery was going to be turned it into a carpark, with some of the surrounding forest already cleared.

While this would naturally make the families of those who were buried there upset, it also made other groups of people worried.

But… who *are* the people buried in this cemetery?

According to eyewitnesses who saw the people buried there, they were the victims of the May 13 racial riots.

The racial riots officially caused 200 lives to be lost, although some claim it much higher. While there are plenty of sites and news stories that offer an explanation of what really happened, those of us born after the 13th May event (e.g. everyone at CILISOS) may not understand what exactly caused it. All that we know about the incident are what had been passed down to us through reports, blogs and stories from the survivors.

This is one of them.

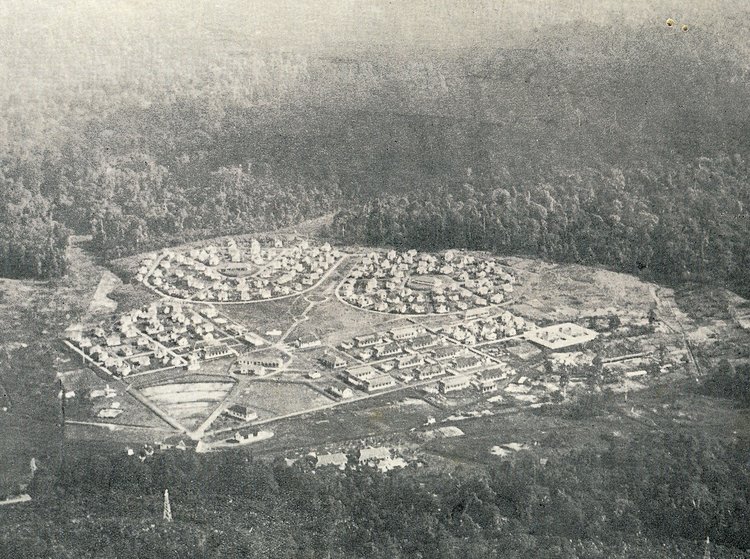

Before the Sungai Buloh Hospital was built, it was a leprosy settlement where lepers lived called the Sungai Buloh Leprosy Settlement (SBLS). Established in the 1930s, leprosy patients were brought from other leper asylums in the country to live away from society, as they go through rehabilitation and receive medical treatment for their disease.

Often called the Valley of Hope by the patients for the lush scenery and remote location, it gave hope to the patients that they would be be able to rejoin society once they were healed. But their quiet life would be disrupted one day in 1969.

One of the residents who lived at the SBLS remembered the time when lorries came to the land where the cemetery was built.

He described that several lorries came to the settlement, accompanied by government officials. When people got curious, they were told to look elsewhere.

“We saw several lorries entering the settlement in the few days after the tragedy, but we were ordered to look away,” – Lee Chor Seng, former resident of the SBLS, The Star.

Then more lorries came.

“When the last few lorries made their way there, we could smell the putrid odour even from far away,” – Lee Chor Seng, former resident of the SBLS, The Star.

At first, the residents of the SBLS did not know what was causing the smell, and the government officials were being very secretive. However, two of the patients were eventually called to help and they found out what it was; it was the stench coming from the dead bodies of the May 13 incident.

According to another SBLS resident at the time, the bodies that were brought in were covered in black tar, making it hard to identify them by their skin color.

There were also testimonials from doctors who worked in the Kuala Lumpur General Hospital in 1969, when bodies that were brought there were tarred in the morgue, before being sent out to be buried.

According to records from the National Operation Council, 103 bodies were buried here.

While some families were able to trace their dead family members to the cemetery, some were only able to find the place after the news of the cemetery was reported.

“These are cases where the family found out that the victim was buried here. Most of the affected families did not know because the situation was very chaotic then,” – Kuala Lumpur and Selangor Chinese Assembly Hall chief executive officer Tang Ah Chai, The Star.

After the ‘rediscovery’ of the cemetery, ordinary people started working to give it a new life

Families upgraded the headstones of those who died, and paid more frequent visits to them to clean and clear the weeds around their graves. The local municipal councils even helped to repair some of the damaged headstones, clear away all the weeds and even put a fence around the cemetery.

In April 2017, during the Chinese season of Qing Ming, a memorial service of multiple religions was conducted for the victims buried in the cemetery, including 2 Indians and 2 Malays who were also buried there.

Some shared about how relieved they felt when they were able to reconnect with those who were buried there, and the new state of the cemetery.

“I believe he would he happy getting so many visitors and to have the area cleaned up nicely. Some years when we came for Qing Ming, the weed was tall reaching our heads,” – How Swee Ling, whose father was killed in the May 13 riots when he was working in Kampung Baru, The Star.

Other shared their stories of how they lost their loved ones to the racial riot. For some, the loss was too much to bear like garage owner Tay Lian Chin. His house was burned down when 15 of his family members were gathered at his house to celebrate his first full moon.

He lost 9 family members that day, including his grandfather, sister and uncles, barely escaping with his mother.

“10 years ago, I always brought my mother to visit the graves. She would always cry when he remembers that day. Now that she has passed away 2 years ago, I think she would be comforted to see today’s memorial service,” – Tay Lian Chin, eNanyang.

But what about the car park?

Since the news about cemetery being possibly turned into a car park, families, researchers and NGOs have asked for the cemetery to be preserved.

Fortunately, the local municipal council had heard about the clearing around the cemetery and found that no one had request any permit to clear the land surrounding the cemetery. Since it was illegal, they have also issued a stop-order on the unknown developer.

Furthermore, given the victims who were buried in this cemetery, then Subang MP R. Sivarasa has proposed that the cemetery be turned into the heritage site by the National Heritage Department, with the support of the state government. A Facebook group had also been created to monitor that no development would affect the cemetery.

While May 13 remains a taboo topic that could incite political tension between the races today, and often used as a threat to other races, some scholars think that the subject of May 13 should be seen in a more positive light, talked about, examined and learned from.

“The cemetery marks a heartbreaking tragedy in the country’s history. It must not be erased because we all learn important lessons from history. This serves as a reminder that the racial harmony Malaysians enjoy today should not be taken for granted,” – Kuala Lumpur and Selangor Chinese Assembly Hall chief executive officer Tang Ah Chai, The Star

Tensions between Malays and Chinese have always been there (whether we choose to acknowledge them or not), and anyone who has lived through a Malaysian general election will attest that the same tensions are used by politicians on both sides today. While nothing as bad as May 13th has happened in Malaysia since, it’s important to note and acknowledge this moment in history, to remember where we don’t want to go again.

- 14.5KShares

- Facebook13.0K

- Twitter137

- LinkedIn136

- Email209

- WhatsApp916