Taman Negara may not have existed today, if it weren’t for this persistent British hunter

- 652Shares

- Facebook613

- Twitter8

- LinkedIn2

- Email5

- WhatsApp24

If you enjoyed this story and want more, please subscribe to our HARI INI DALAM SEJARAH Facebook group ?

Show of hands: who here has actually been to the Taman Negara?

It may sound weird for us to suddenly talk about the National Park, but recently it was announced that the entrance fee to it will increase from RM1 to RM30! And apparently, this is the first price increase in the last 70 years.

“The revision is part of initiatives to improve efficiency and reduce revenue leakage, aside from increasing income which will help the state become independent. Greater revenue will benefit the rakyat through aid and development projects,” – Datuk Seri Wan Rosdy Wan Ismail, Pahang’s Mentri Besar, as reported by The Sun Daily.

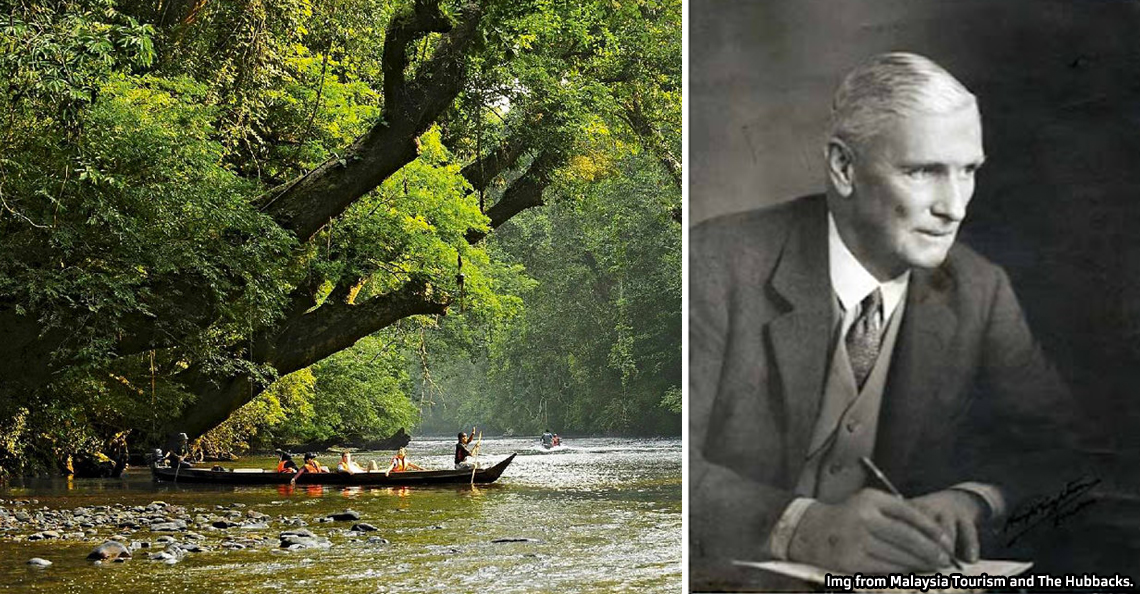

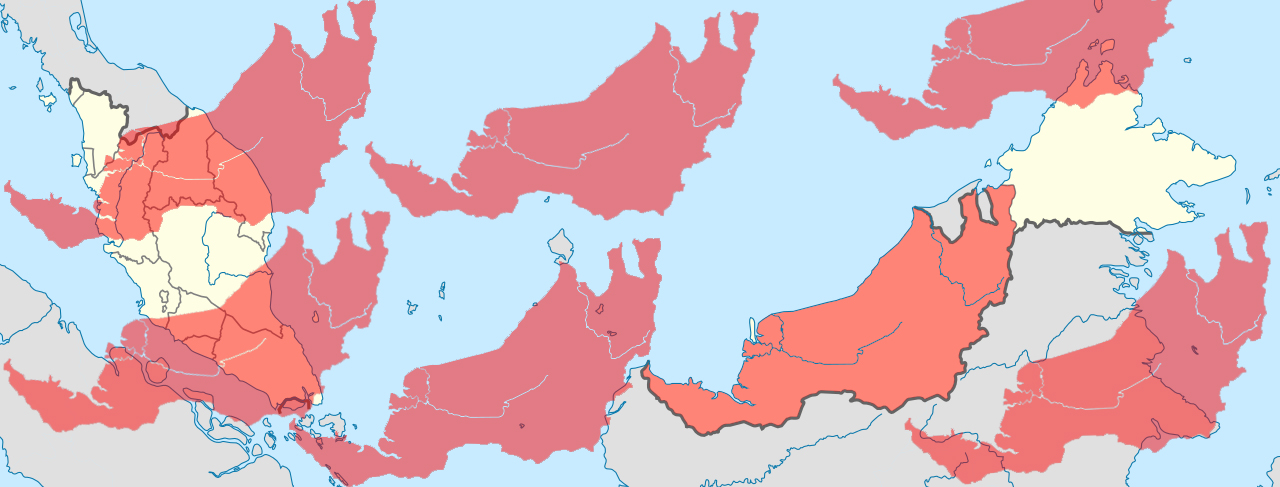

For those not familiar with it, the Taman Negara actually spans three states (Pahang, Kelantan and Terengganu), and besides leeches and river boat rides, it’s probably most famous for the tallest peak on Peninsular Malaysia, the Gunung Tahan.

We were actually less interested in the price increase (it’s bound to happen sometime) but the 70 years thing kinda intrigued us. It would have meant that the Taman Negara was established sometime back in the colonial days. But why would the British, whose primary concern was making money out of its colonies, be concerned with establishing a huge park that spans three states?

The story behind it was pretty interesting, because for one thing…

It was started by a renowned hunter who decided to conserve wildlife instead

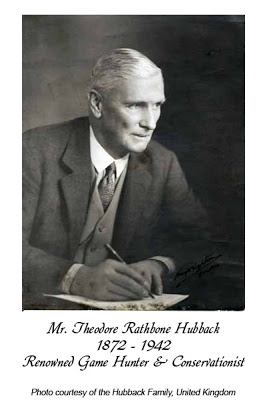

Meet Theodore Rathbone Hubback.

If you’re a fan of hunting literature, you might have noticed the name from some of his books, like “Elephant and Seladang Hunting in the Federated Malay States” (1905) and “Big-Game Shooting: with an article on the Tiger” (1924). Or, if you’re a wildlife enthusiast, you might have noticed that this guy gave his name to our second largest land mammal, the Malayan gaur (seladang), Bos gaurus hubbacki.

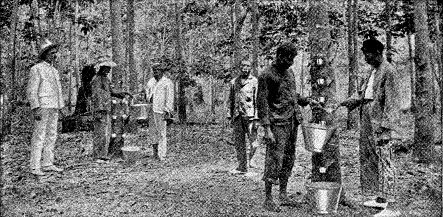

Right off, we know that this Hubback guy seems to have an interest in animals, but Hubback was many other things throughout his life. Born in Dec 1872 to the Lord Mayor of Liverpool at that time, Hubback first made his name playing cricket for Lancashire. In 1895 he moved to Selangor, Malaya, and made a living as a civil engineer/contractor there. He also ventured into rubber planting, and at that time plantations were fairly new in Malaya.

While today plantation pests are most commonly rats, back then the pests were a lot more spectacular, including rhinos, tapirs, elephants, deer and wild pigs. And gaurs.

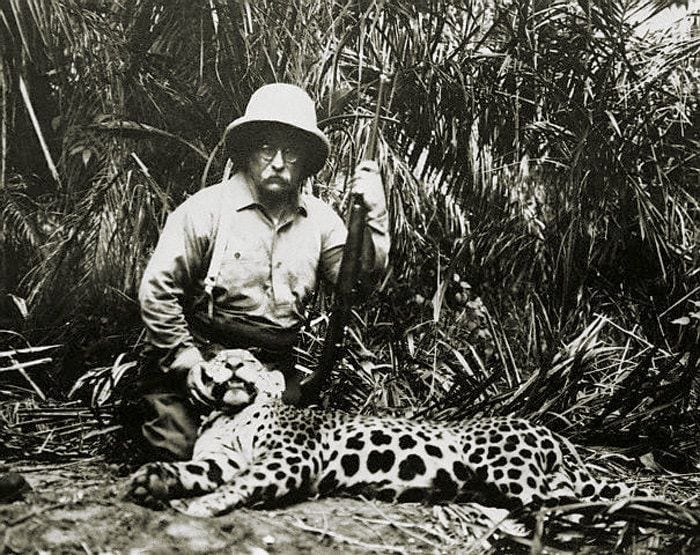

The shrubs and the succulent rubber saplings within rubber plantations attract herbivores, and they in turn attract carnivores like tigers. Wildlife was so commonly seen at plantations back then that many European planters did a side-job as hunters as well, creating the planter-hunter class (or planter-shikari, as they’re sometimes known for some reason).

Hubback seemed to have been one at some point, but it was said that he was more interested in the natural world than rubber planting though, so shortly after the first World War, he left Malaya for Alaska to study a rare breed of sheep. It was probably during his time in North America that Hubback made the switch from a big-game hunter to a fervent wildlife conservationist, after…

Hubback got inspired by the American president who inspired teddy bears

We’d like to point out that the guy who inspired Hubback also shared his first name: Theodore Roosevelt, the 26th American president. Roosevelt was famously known to hunt, but it was said that his many writings of his hunting trips were often laced with concern over loss of species and habitat. He was also famously known as the origin of the teddy bear’s name, due to his hunter’s sportsmanship: he refused to shoot a bear captured by other hunters, an incident that became viral and spawned teddy bears.

When Roosevelt became president in 1901, he used his authority to protect the wildlife of the US by creating a Forest Service (USFS) and establishing

- 150 national forests,

- 51 federal bird reserves,

- 4 national game preserves,

- 5 national parks,

- and 18 national monuments…

…altogether protecting 230 million acres of public land in the US during his time. That’s like 7.5 Sarawaks of habitats protected!

Roosevelt may not have been the only source of inspiration for Hubback, but he may have been the most prominent. So when Hubback returned to Malaya sometime in 1920, he settled down in a remote Pahang village and began his campaign to save Malaya’s wildlife.

At that time, wildlife hunting in Malaya was regulated through a system of revenue-generating hunting licenses based of the closed and open season concept. These licensed hunters, as well as planters being too liberal with their bullets (they have the permission to hunt under ‘defence of property and person’), led to a noticeable decline of wildlife around that time.

It should be noted that some official institutions at that time, like the government’s museum service, were aware that Malaya’s wildlife was being pushed to extinction. However, lacking the power to change anything, they focused instead on collecting fauna specimens to keep them in their museums. Hubback, however, was more motivated, and through his campaigning he managed to get the wildlife laws in the Federated Malay States (FMS) upgraded in 1921.

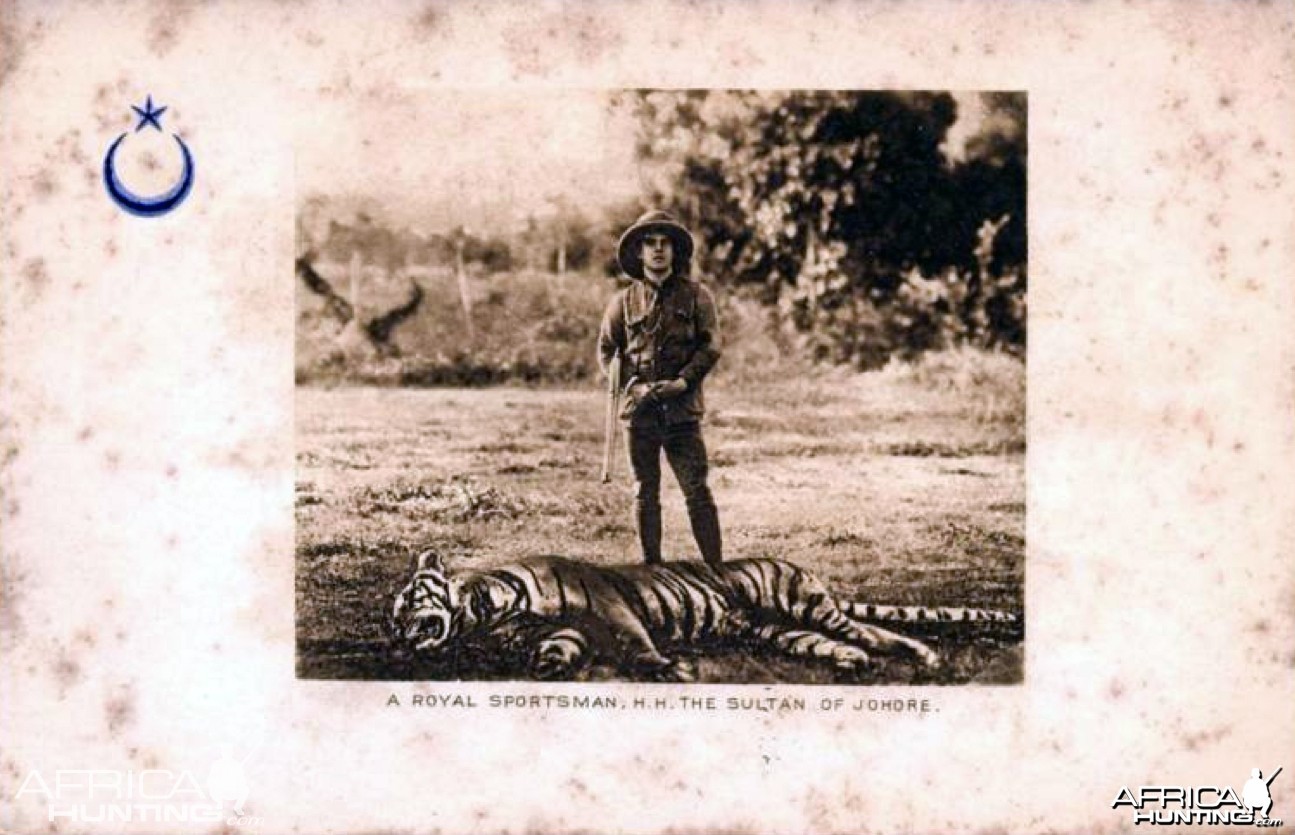

This new law allowed for State Game Wardens, but at the time it wasn’t provided for them to be appointed with salaries, so Game Wardens in the FMS at that time were hunters who volunteered to help. An exception to this was in Johor, where Sultan Ibrahim, a game hunter himself, fully supported game protection and appointed a salaried game warden. Wildlife protection laws for some species were also extended to states outside the FMS like Kelantan, Terengganu and Johor.

From 1921-1937, with the support of the respective Sultans, Hubback established seven wildlife reserves in Perak, Pahang, Negeri Sembilan and Johor. However…

The government and planters prefer money from agriculture to having elephants

As we’ve mentioned earlier, this story took place at a time when wildlife that are rare today were still considered as plantation pests back then. So you can probably imagine the opposition Hubback faced from both planters and the colonial government, which prioritized agriculture.

Hubback realized that without proper laws and a proper Game Department (where people actually get paid), there won’t be much impact, so in 1925 he went to London to try and gain support with the admins of the British Empire. Perhaps not so coincidentally, wildlife conservation had became a trendy topic among politicians in London at the time, especially as they had just signed an international petition to stop the destruction of wildlife in their colonies in Africa.

Hubback’s proposals for conservation was very well-received by Britain, strings were pulled, and on his return to Malaya, with the approval of the Colonial Office he established a formal Federal Game Department. However, things didn’t improve much. Although he gained the sympathy of officials in London, officials in Malaya were more indifferent to the change, and some of the States failed to allocate any funds towards game protection.

The Rubber Growers Association (RGA), a staunch opponent of laws protecting crop-raiding wildlife, had also called for their total withdrawal, highlighting their crop losses. Despite being a hunter himself, the Chief Secretary at that time, George Maxwell, had to agree with the RGA as agricultural interests are ‘paramount and must prevail’. In 1928, the wildlife laws were amended so that planters with permits can shoot at elephants within a half-mile radius from any cultivated area, and it soon turned ugly.

Since the permits had to be issued by either a penghulu (chief) or a district officer (DO), this effectively takes the decision from the professional judgment of Game Wardens and into the hands of civil servants. Even worse, misgivings from the event caused some DOs to order Game Wardens to kill the offending elephants, which basically meant that Game Wardens were protecting crops rather than wildlife. Hunting for ‘pests’ became a lucrative business, and some were even reported to plant crops in remote areas for an excuse to hunt wildlife.

This ongoing conflict between plantations and wildlife (which still happens today btw) had put the government in a tough spot. Whatever will they do?

As a sort of compromise, Hubback proposed a national park

Remember the part about Hubback establishing seven wildlife reserves from earlier? One of them was the 1,425 square kilometers area near Gunung Tahan, called the Gunung Tahan Wildlife Reserve. Since they were looking for a solution to the wildlife problem and all, in 1927 Hubback proposed to extend that existing reserve all the way to the headwaters of the Terengganu and Kelantan rivers, and make it into a National Park.

Initially, the High Commissioner of Malaya, Hugh Clifford, had rejected the idea as it might close off jungle roads used by the local people, but then the big boys entered the lobby. W.G.A. Ormsby-Gore, Britain’s Parliamentary Under-Secretary, aka the guy Hubback talked to during his last trip to London, visited Malaysia in 1928. He was persuaded by Hubback that a national park will be tangible solution to the wildlife conflict, and caught between a rock (angry rubber planters) and a hard place (Britain’s Colonial Office), Clifford eventually agreed to the national park.

However, the agreement came at a price: since there will now be a big enough place for wildlife conservation, wildlife preservation efforts outside the national park should not be ‘taken too far’. As in, wildlife protection laws outside of national parks will be relaxed. Also, because Clifford also interpreted wildlife conservation as ‘preserving their species’ rather than ‘protecting their habitats’, having a national park that large would make all the other smaller wildlife sanctuaries unnecessary.

This led to the removal of protection for elephant and sambar deer (considered to be most destructive to crops) outside the planned national park, as well as the abolishment of most other wildlife sanctuaries at the time. There were some other disagreements along the way between Hubback and pretty much everybody, but the national park slowly took shape.

The economic depression around the time also slowed down the establishment process a bit, as a national park seemed counterproductive to the economy. However, the people supporting the park were quick to point out that it’s possible to profit through tourism.

“Why ignore that wildlife is one of the resources of the country? It is so recognized in North America, in South Africa, and many other countries. It is probably not recognized as such in China, Tibet or Siberia. Whom shall we follow?” – Theodore Hubback, as quoted in “Civilizing Nature: National Parks in Global Historical Perspective“.

Sir Thomas Comyn-Platt, a representative of the sorta influential organization called the Society for the Preservation of the Fauna of the Empire (SPFE), had explicitly vouched for the park’s potential after a boat ride down Tembeling River, which helped push things along. Also, in 1935, the Malayan rulers of Pahang, Kelantan and Terengganu agreed to name the park as the King George V National Park, in commemoration of the monarch’s 25th Jubilee celebrations.

After much legal and administrative delays, the park was finally formally established in 1939.

And that’s the story of how Taman Negara came to be

While the King George V National Park can be said to be largely due to Hubback‘s tenacity, it was that tenacity (as well as his reputation as a ‘tactless wildlife fanatic‘) that got him finally terminated as Malaya’s Honorary Adviser for Wild Life. Comyn-Platt was eventually persuaded that game preservation could never work as long as Hubback kept making things hard for the government, who tried to compromise between agriculture and wildlife protection.

Although Hubback’s vision was ironically said to work better without him in it, he did set the stage for the conservation of wildlife in Malaysia. Hubback and other ex-hunters was said to start the trend of capturing wildlife on camera as opposed to killing them and taking trophies, and the King George V National Park, like several others like it around the globe, signaled the emergence of nature appreciation as popular culture. His efforts in wildlife protection was also the precursor of today’s Jabatan Perhilitan, as well as the start of better legislations that protect wildlife in Malaysia.

After surviving the Japanese occupation and the struggle towards independence, King George V’s National Park went relatively abandoned for a while, until Malaya’s independence in 1957. It was then renamed as Taman Negara, and in doing so shed its past attachments to colonials and became a sort of national symbol of the new nation. All in all, it has been one heck of a journey that wouldn’t have happened if not for a very persistent tree (animal?) hugger…

…and next year, you need RM30 to enter. Sigh.

If you enjoyed this story and want more, please subscribe to our HARI INI DALAM SEJARAH Facebook group ?

- 652Shares

- Facebook613

- Twitter8

- LinkedIn2

- Email5

- WhatsApp24