How did this RM15K Sabahan fish confuse scientists around the world?

- 268Shares

- Facebook224

- Twitter9

- LinkedIn6

- Email9

- WhatsApp20

Do you guys remember that RM1000 siakap incident? For those of you who don’t, it’s about this guy who was charged around RM1000 for a siakap in this floating restaurant in Langkawi. The guy said he and his friend were shocked when the siakap was served to them in 5 plates. They eventually learned that those 5 plates were equivalent to around 7kg siakap.

Of course, this triggered an online outrage, calling for a boycott of the restaurant. However, among the comments left by the netizens concerning this situation, there was one comment that intrigued us; a fish known as kelah could reach a price tag of RM15k seekor! That’s insane, considering you can buy a shark for less than RM20 on this website, which begs the question…

How did a fish end up that pricey?

Ikan kelah, also known as empurau or ikan pelian, is apparently a prized catch (heh) among food lovers in Malaysia. People who have tasted it describe its flesh as chewy and fatty, with hint of sweetness. It is said that the kelah feeding on the fruits found on the riverbanks is what contributes to its fatty taste and distinctive fragrance. Due to said unique flavor, we found out that can actually fetch a very high price on the market; it could go up to RM1000 per kilogram.

Looking at its price tag, it is usually bought by rich people and politicians:

“This is a golden fish and only the rich and politicians will buy them as festive gifts. The buyers are usually from outside – Sibu, Kuching or Kuala Lumpur,” – fish monger Ong Ee Ching, as quoted by Borneo Post Online.

Its size also plays a big factor in its asking price. Despite everything, we couldn’t find any reliable sources showing that kelah is sold RM15k seekor…but there have been records that kelah can grow to a size of 54kg, so RM15k for a particularly massive specimen isn’t that far out of the question.

Sadly, its price tag is also what makes wild kelah so over-hunted. This situation is aggravated by the fact that some people prefer wild kelah than cultured kelah, because the texture and the taste of the flesh of wild kelah is, by some accounts, better than bred kelah.

What’s more: kelah is slow-growing, reproduces seasonally and is especially sensitive to the quality of water that it lives in. All those factors have caused the species to be in their current state… a state of limbo, that is.

The kelah’s conservation status is “Data Deficient”…?

There are 3 species of kelah in Malaysia. They are Tor tambroides, Tor tambra and Tor douronensis. Taking a look at the website of IUCN red list of threatened species shows us that the various species of kelah are classified as “Data Deficient”… meaning there is still not enough data on their distribution and population status to assign conservation status for them.

We also did a search for the Tor douronensis in the IUCN website, and unfortunately, it’s not listed there. That could mean that the species as a whole hasn’t been evaluated yet, or in a more likely scenario, it’s not recognized as legit species at all (even though the matter is still under debate).

The lack of conservation status by IUCN further affects the local conservation policy and protection efforts for the kelah, because our government refers to IUCN red list as a guideline to do just that. As of today, all the three species of kelah mentioned are not classified as protected species under the Peraturan-Peraturan Perikanan (Pengawalan Spesies Ikan Yang Terancam) 1999.

But why is there a deficiency on the kelah? Well, an article published in 2019 suggested that categorizing these fish have been difficult due to the taxonomic ambiquity among the kelah species in South East Asia.

Basically, researchers haven’t had to chance to properly distinguish them yet because they have different anatomical features depending on the environmental factors and localities of any one species. And if they don’t clearly know what a species looks like, it is difficult to know its distribution and population status.

The overhunting and the lack of a conservation status of kelah has created a vicious cycle, resulting in the decreasing population number of kelah in the wild.

Less wild kelah could endanger this Eastern Malaysian traditional cuisine

Back in 2018, this writer visited this village, Kampung Nuntunan in this small town called Apin-Apin in the Keningau district, during my internship in Department of Fisheries Sabah, and from his experience there, it’s safe to say that kelah is very important to this community.

The fish is used for making a traditional Kadazandusun food called bosou. The recipe is simple: all you gotta do is ferment fresh kelah with rice, salt and buah keluak – a type of natural preservative. Once it’s been fermenting for two weeks in an airtight jar, it is then served “fresh” or stir-fried with chilli and garlic before serving.

Some people have commented on its strong smell that might not make it a super mainstream dish, but it has found a hardcore fanbase throughout the years.

During this writer’s stay in Kampung Nuntunan, a strong debate among the villagers broke out when the question was asked: “What’s the best way to cook kelah? Some argued it was best served fried; some said steamed, and another would say grilled. Nevertheless, there was this one kelah-based dish that everyone agreed on was the best; and that’s bosou.

This is how significant kelah is to the Kadazandusun people. Sadly, the decreasing numbers of wild kelah is making it harder for the villagers to secure enough kelah for making bosou.

The kampung folk have a DIY system in place to protect kelah

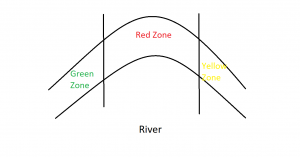

The folks in rural Sabah have inherited a community-based river conservation system passed down by their nenek moyang called “tagal”. Under the system, a specific stretch of the river in their community will be divided into red, yellow and green zones.

Fishing is prohibited in the red zone; fishing is allowed once every two to three years in yellow zone, and in the green zone, fishing is allowed all year round.

A tagal must be registered with the Department of Fisheries Sabah, and each tagal must have a committee overseeing its management.

Here’s the best part: if anyone is found violating a tagal, they will be punished with “sogit”, which is kind of like denda. The “sogit” can be in monetary fine, BUT it can come in the form of kerbau too. Yup, you heard that right, you can pay denda with kerbau.

And it’s legit, tagal can be enforced under the Native Customary Law and the Sabah Inland Fisheries and Aquaculture Enactment.

The Department of Fisheries Sabah has expanded this system to the whole of Sabah, and Kampung Nuntunan’s tagal is one of the hundreds of tagal that have been established in Sabah.

Other successful examples of the system include tagal Sungai Moroli in Kampung Luanti, where you could get a special massage session from their specially trained kelah. As of December 2021, there were 563 tagal registered in Sabah.

There are actually kelah sanctuaries in West Malaysia too

Although tagal isn’t native to the Semenanjung, kelah sanctuaries have been established in many states over here; the most well known ones being the Lubuk Kejor Kelah Sanctuary in Tasik Kenyir, Terengganu, the Lubuk Tenor Kelah Sanctuary in Taman Negara, and the Chiling River Fish Sanctuary in Selangor.

These kelah sanctuaries are different to the tagal system wherein fishing is prohibited completely; they’re there as ecotourism destinations. Moreover, kelah sanctuaries are mostly taken care of by the state and federal government agencies.

However, the core issue still remains. As long as there is a huge demand for kelah – reflected in its expensive price tag – wild kelah will continue to be vulnerable if it is not classified as protected species.

While most of us cannot help out scientists in classifying the fish, you can visit any of the tagal or kelah sanctuaries that are open to visitors. For a small entrance fee (that’s used for the upkeep of these sanctuaries), you too can check out the legendary RM15K fish and help conserve it, in a way.

- 268Shares

- Facebook224

- Twitter9

- LinkedIn6

- Email9

- WhatsApp20