40 years ago, Roti Canai was same price as Mee Rebus. Why hasn’t it gone up as much?

- 2.6KShares

- Facebook2.6K

- Twitter5

- LinkedIn7

- Email7

- WhatsApp26

Two years ago, we started noticing something. That Roti Canai is still very cheap, despite other food prices going up. We wanted to run the article that Deepavali, but we forgot. Then the following year, in the midst of a busy period, we forgot again 🙁 So this year, we set a reminder.

And then, we checked around. We asked our colleagues, their parents, rotui canai owners, and a whole bunch of other people for the prices of roti canai and kaifan (chicken rice) in the 70s and 90s… and so we verified lor…

40 years ago, roti canai was about 30 sen, and a mee rebus was about 70 sen

“Grandpa gave me RM1 to spend on supper for the 5 of us and still expected some change back, remember?” – one CILISOS parent recalling life in the good ol’ 70s

Most of the people we asked couldn’t remember the prices in the 70s well, and even one of the neneks said that she hardly ate out back then. But one of the moms told us that she remembered having roti canai in Terengganu for 25 cents in the 70s. We also found evidence of prices of Mee Rebus in Teluk Intan to be around 50-70sen.

Another uncle pointed out that, during his primary school days (in the 70s), roti canai was not on the menu, only economy mee or mee hoon, the price of which he tried to recall as 10 cents. He added that many places used to charge 10 cents for food, like this one shop in the Rawang market.

“Economy Mee Hoon and Tong Sui cost 10 sen. Sometimes, we have supper of kon loh mee with minced meat and unlimited free soup. Also for 10 sen.”

He also mentioned that kai-fan was a luxury back then, and one of the few places selling it was Nam Heong on Sultan Street. No single portions were given, so price estimates for single portions were difficult to obtain.

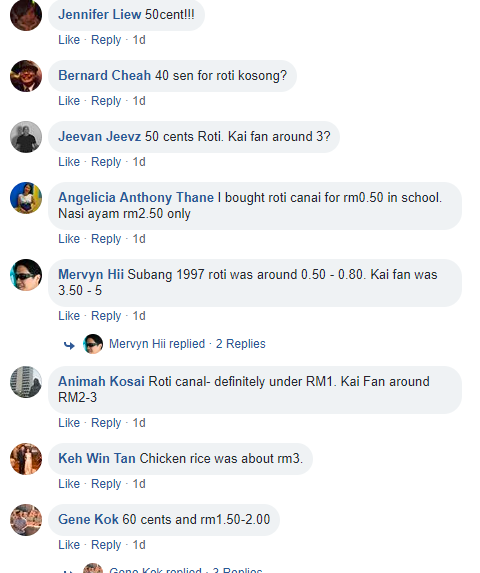

But for the 90s, we received a lot of responses, though they’re mostly from (but not limited to) KL and Selangor.

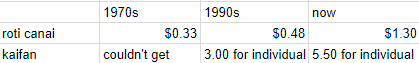

Anyway, we compiled these prices (along with current prices) and calculated the average estimates to make a simplified comparison in the size of increase of their prices.

From what we can see, it seems that in the 70s, roti canais were not that cheap by comparison – around 33sen. This matches quite well with the figures we got from PRIMAS (Malaysian Indian Restaurant Owners Association), which was estimated by one of their older member restaurants.

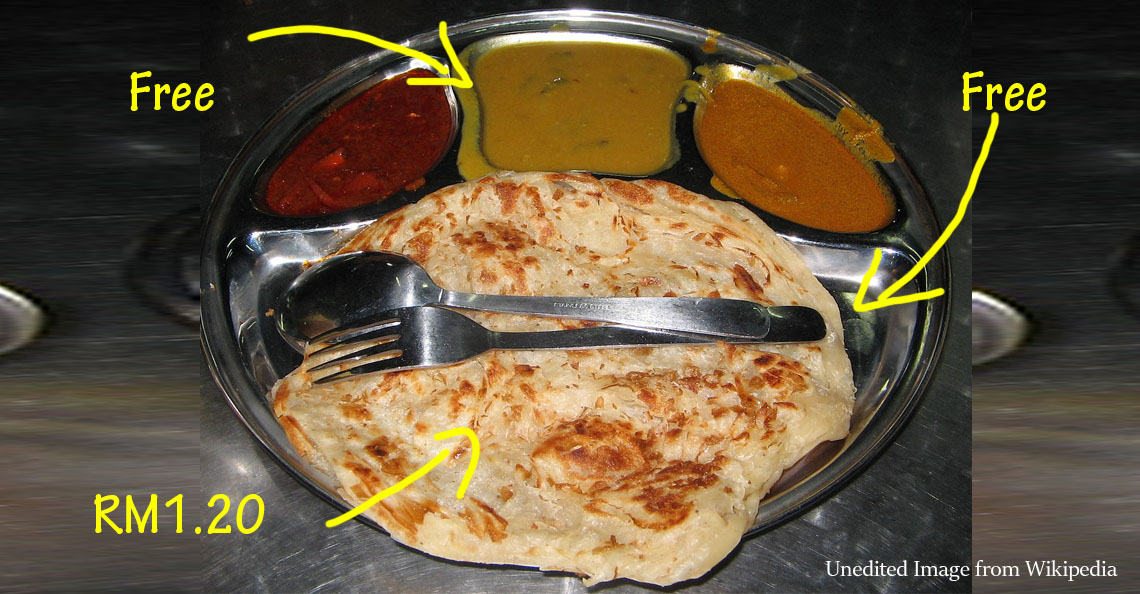

- 1970s: RM0.30

- 1980s: RM0.50

- 1990s: RM0.70

- 2000s: RM1.00

- 2010s: RM1.20

- 2018: RM1.50

Fast forward to the 1990s, and the price rose, but still at a relatively affordable 40 to 50 sen. It’s only in the last few years that the price doubled – nowadays, it’s common to see roti canai being sold at RM1.20 like Sri Melur Jaya or RM1.30 like Chang Wah Tey. Strangely enough, even Pok Sid Roti Canai Samah and a restaurant in Jalan Tok Keramat still sell roti canai at 50 cents!

And think about the cutlery that you get in the restaurants. Have you realised that the roti canai is served with metal forks and spoons on a metal plate with free dhal?

We reached out to a few peeps to learn a little more about this including the Malaysian Muslim Restaurant Owners Association (PRESMA) and PRIMAS. FYI, PRIMAS is for any Indian restaurant and that includes mamaks as well (not just banana leaf places).

Why the Roti Canai price doesn’t seem to go up much one?

According to the peeps we spoke to, the reason is the high price sensitivity of roti canai customers, especially those who opt for cheaper meal options. In restaurants, the roti canai and teh tarik are frequently ordered items, and so things get very competitive. So restaurants are very hesitant in raising the price for fear that they’ll lose their customers to competitors.

The people at Kanna Curry House added that the price they’ve been charging for roti canai remained the same since they can absorb the increase in the major costs of making it. High sales volume due to high demand is enough to cover the costs and make profits.

“Roti canai sale varies from each branch, but mostly the demand is great from customers.”- Yoga, a managerial member of Kanna Curry House.

Absorption of roti canai costs is possible for those with a wide range of food products because of the diverse range of income sources. So boleh tahan lah with so much food…

However, we were told that raw materials alone don’t influence the prices. There are other factors like operating costs (rental, water, electricity, levy, salary etc), which PRESMA insisted are pretty hard to compare, so kenot make comparisons of prices in different outlets.

PRIMAS also gave us the breakdown of the costs: for every piece of roti canai,

- 20 sen for 1 piece of roti canai dough,

- 5 sen for oil and planta,

- 15 sen for roti master’s wage,

- 10 sen for electricity and gas,

- 20 sen for dhal curry and sambal, and

- 15 sen for cleaning expenses.

- TOTAL estimated cost per roti – 85 SEN. (Ok what still got 40% margin wei!)

In most places, certain ingredients like egg and sardine have a bigger influence on the prices than flour alone, judging on the gap between the prices. One mamak we visited sells roti kosong at RM1.20 and roti telur at rM2.50 while Kanna sells roti kosong at RM1.50 and roti telur at RM2.70.

“It depends on the additional items.” – said the mamak.

PRIMAS told us that the customers tend to underestimate the work that goes into making a modified roti. Extra ingredients and some extra work are needed to make it. And some restaurants add some special ingredients, like masala powders for fragrance and margarine for crispiness.

“Especially among Indians. When they come to Indian restaurant, they feel more at home. So like the comments they give in their own house, they will start giving comments lah [in the restaurant]. Because the racial attachment is there.” – PRIMAS added about the customers’ mindset.

In 2017, PRESMA, which has no authority to control the prices, told NST that members can’t simply raise their prices because an unjustified increase in prices would be punishable under Section 53A of the Price Control and Anti-Profiteering Act 2011.

In 2016, the govt removed the RM8.25 subsidy per 25kg bag of flour. When we asked anonymous mamak and KCH about the removal of this subsidy, they told us that they never received any subsidy on their goods including the flour despite being members of PRESMA and PRIMAS respectively. So not much has changed in the way they handle their businesses. In fact, Yoga said that the guys at Kanna weren’t aware of it.

“Anyway, we get one of the good qualities in the market, Tepung Gandum Bluekey.” – Yoga added.

So it’s actually the restaurants that wanna keep it affordable <3, and some are even thinking of LOWERING the cost!?

As a member of PRESMA, one mamak near the CILISOS office doesn’t feel like they’re subjected to any restriction since they sell their roti canai at a relatively low price than what the others are selling. It has been selling their roti canai at the same price (RM1.20) over the past 8 years of business. In fact, it is actually thinking of LOWERING THE PRICE!?!

This mamak wants to reduce it to RM1 because most poorer people or people with lower purchasing power like blue collar workers and students would opt for cheaper stuff like roti canai.

“Normally, RM2 is ideal for a meal of roti kosong and teh O”

This is a pretty noble thing to do, since various uni students interviewed by NST declared that food and transportation are a huge chunk of their expenses.

“Daily meals cost more than RM10 and are the bulk of my expenditure. I also spend quite a bit on transport, commuting between the apartment and the university.” – Auni Zulfaka told NST.

According to the Department of Statistics Malaysia (DOSM), the food cost in September 2018 is 0.5% higher than the food cost in September 2017. A study by the International Islamic University Malaysia (IIUM) found that food inflation here depends primarily on world food commodity prices and real effective exchange rate, while labour cost seems to have very little effect on food price inflation. Well, speaking of labour…

Roti is cheap, because labour is cheap… and that’s not necessarily a good thing

PRESMA and PRIMAS are more like unions for these restaurants to air their grievances and find solutions to their problems, which are sometimes raised to the govt depts (particularly Domestic Trade, Cooperatives and Consumerism Ministry [KPDNKK]) since it’s these depts that are in charge of the rules and regulations of these restaurants. They also have guidelines for restaurants that need help with things like cleanliness and HR.

“Primas has always helped in foreign workers issues & brainstorming on how to get to a better level.” – said Yoga.

One of the motivating factors for the formation of PRIMAS is the shortage of labour back in the 1990s. According to PRIMAS, initially, the older of generation of Indian migrants were heavily involved in the restaurant business.

“Somewhere in the 60s-80s, my father’s employees were those who were holding red or blue ICs but they have contacts and families in India. So they come here and work here for about 2 years or any number of years according to need. And then, they’ll go back for a short holiday and then they come back.” – said the PRIMAS president.

But later on, as the country grew, a lot of other opportunities came up, so many locals have no interest in working in this type of restaurant environment.

“It will be their laaasstt priority, you know. So all this while, we were facing a shortage. In 1996, when Tun M said restaurants can employ foreign workers, then we had some space to breathe. that’s where the boom of industry came.” – PRIMAS.

And after all, why would businesses want to hire an unmotivated local, when they can hire a well-motivated foreigner for less money? A past CILISOS article wrote about how much (or how little?) foreign workers earn in Malaysia, but that’s a topic for another day.

For now, it’s getting harder for Indian restaurants to hire people, since the freezing of intake of foreign workers two years ago. PRIMAS said that restaurant associations wanted to bring in 1.5 million Bangladeshis but the foreign worker policies were changed to benefit “a few individuals”.

“Workers have to leave for holidays or go back once their contract is finished. They don’t even give us replacements.. We don’t have new approval for replacements. Then, how would the industry survive?” – PRIMAS.

It’s to the extent that sometimes, owners are forced to hire illegals because of the owners’ needs for relevant staff and the workers’ have to put food on the table. PRIMAS recently attended a townhall session in Putrajaya where a panel for foreign worker issues was made (Jawatankuasa Pekerja Asing), consisting of a judge, lawyers and human rights activists.

With a new government in place, perhaps a solution can be found that lets everyone enjoy our land and its bountiful food, maybe even at a slightly higher price. But for now, while you can still enjoy a roti canai for RM1.20 (or RM1 – just ask us where!), maybe Deepavali is a good time to appreciate how wonderfully affordable our Malaysian food is, and the sacrifices that are made to keep it that way. 🙂

- 2.6KShares

- Facebook2.6K

- Twitter5

- LinkedIn7

- Email7

- WhatsApp26