Gomen proposes keeping DNA data on rakyat. Actually, they might already have your DNA

- 559Shares

- Facebook542

- Twitter1

- LinkedIn2

- Email3

- WhatsApp11

You would think that with all the tech put into our MyKads, there should be no problem with people forging it, but that notion had been proven wrong time and time again. The most recent news confirmed that: an assistant director of the NRD in Penang was among those arrested and convicted for being involved in selling fake birth certificates and MyKads to foreigners.

It’s a serious crime that the Home Minister Tan Sri Muhyiddin Yassin had called treason, so in response the government had proposed several countermeasures to the problem, like doing more spot checks at NRD branches and rotating the staff among them. Perhaps the most interesting proposal, however, is the setting up of a DNA bank containing genetic data of possibly everyone in Malaysia, and that info will be included in birth certificates in the future.

“The NRD proposed the setting up of a DNA data bank as a long term solution to prevent leakages. The government through the ministry is taking the sale of MyKad and birth certificates very seriously,” – Tan Sri Muhyiddin Yassin, as reported by The Star.

This is still just a proposal at the time of writing, but for a country still struggling with the issue of stateless citizens and having a weirdly sexist citizenship law, a DNA data bank may sound a bit too high tech. Frivolous, even. But you might be surprised to know that…

They already have the DNA profiles of around 0.23% of us

Just in case you’re not familiar with DNA, it stands for deoxyribonucleic acid, a sort of blueprint for how to build a lot of living things. Think of it as the code to an app or game or something. In humans, basically it’s a long chain of information (about 1.5 gigabytes in IT terms) found in most cells, and it can tell you a lot of things about a person, like how they’re supposed to look like, how likely they are to engage in certain behaviors, how long can they live, and how likely they are to get certain diseases, among other things.

Only 1% of the DNA is different for everyone, and since it’s unique, you can use it to identify people with. This is especially useful in forensics: if DNA found in a crime scene matches the DNA of a suspect, then you can be pretty sure that the suspect had something to do with the crime. It would be dandy to have a large pool of DNA data at hand to compare with samples from a crime scene, and that’s the idea behind DNA data banks.

In Malaysia, DNA became a hot topic during the time of Anwar Ibrahim’s sodomy trials. We came up with the DNA Identification Act 2009 (Act 699… hee hee) then, and among other things it basically empowers the police to collect DNA from crime suspects and provides for the setting up of a national DNA data bank, called the Forensic DNA Databank of Malaysia (FDDM), among other things.

Even without the political drama surrounding it, the proposal for the DNA Identification Act had been quite controversial. There were concerns about potential misuse of the law by the government, as well as a lack of safeguards when it comes to personal privacy and liberty. A person’s DNA is practically his or her blueprint, so you can see how people might be iffy about giving it to the government. Or anyone, really.

Anyways, in 2012 the DNA Identification Regulations (P.U. [A] 274/2012) was gazetted, and it details the DNA collection procedure (the police needs to ask permission in some cases), as well as the storage and disposal procedures of DNA samples and data. With these laws and regulations in place, the FDDM (the DNA data bank) was formally established in December 2015.

Unlike the recently proposed DNA database, which will be used for identification and registration purposes, the usage of DNA data from the FDDM is legally only for forensic investigations. As of 2017, the FDDM stores the DNA data of around 74,570 people, or roughly 0.23% of the Malaysian population. Of these DNA data, most belong to convicted criminals, crime suspects and drug-dependent people.

As for how often it helped in investigations, between 2016 and 2018 only 21 matches were recorded (of which 8 were rape cases), or only 0.03% of the total data stored in the FDDM. But that wasn’t really surprising, since the pool of data to match from wasn’t that big to begin with. By comparison, UK’s DNA data bank had data that match 13% of the time, but it contains data for some 2.4 million people.

So the government collecting DNA data won’t be a new thing really, but if they were to go through with the recent proposal, it will be a whole ‘nuther kettle of fish, as…

Most countries with DNA databases have them for crime, but there are exceptions (which didn’t go well)

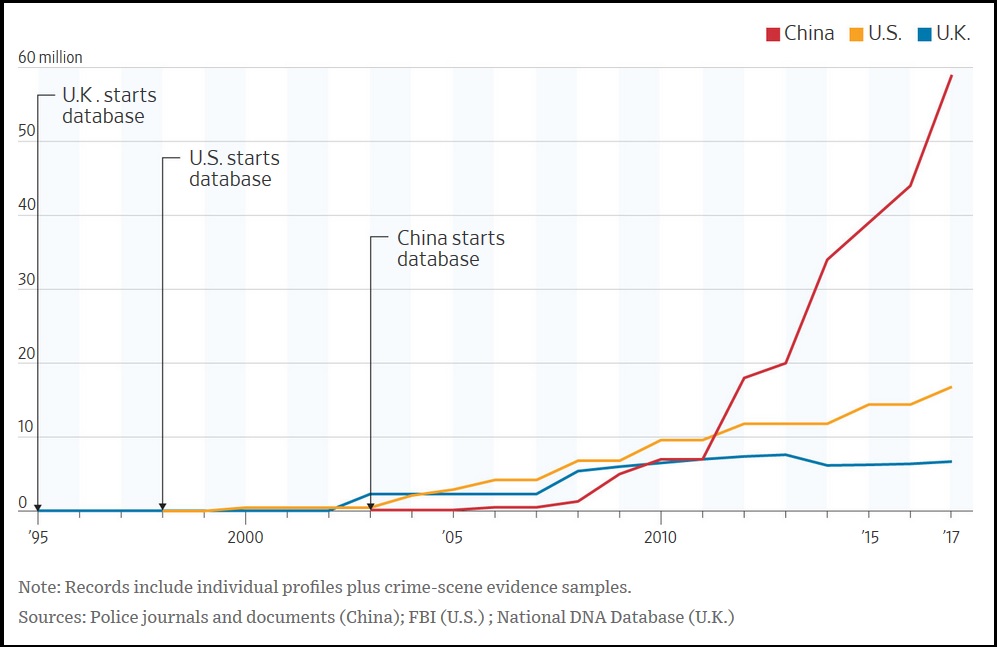

National databases aren’t really rare, as 64 countries (including us) have working forensic DNA databases, with more countries planning to have one soon. The biggest ones belong to China, the USA and the UK.

But they’re mostly for forensics, so most of these countries didn’t try to collect the DNA of every one of their citizens, just criminals and crime suspects (plus voluntary donors for some). But that doesn’t mean that none have tried. The UK, for example, once proposed a DNA database of every citizen and visitor back in 2016, but it didn’t gain support for several things:

- The setting up of the database would be poor use of resources, seeing the low matching rate and the number of innocent people on the database.

- Likely loss of public trust.

- A need to criminalize citizens and visitors who refuse to voluntarily provide their DNA.

- Potential misuse by the police, the State, or potential hackers.

- Increased risk of errors and false matches with crime scene DNA as the database grows bigger.

Other countries managed to get past the launch, but they didn’t last. In 2015, Kuwait experienced a terrorist bombing, and their government’s response was to pass a law that made it mandatory for every citizen, foreigner, and temporary visitor to submit themselves for DNA testing, failure of which will result in prison and a fine. This law, said to be the first of its kind in the world, received heavy criticism for some time before finally being struck down by their Constitutional Court in 2017.

The law was said to violate articles in Kuwait’s constitution that deals with the rights to personal liberty and privacy, and according to Human Rights Watch’s Middle East director,

“The law was an overly broad cudgel that lacked basic safeguards or restrictions, and opened the door to government abuses.” – Sarah Leah Whitson, for HRW.

Earlier this year, for some reason Kenya controversially came up with a new system of identity registration for its citizens, dubbed the Huduma Namba. Among other things, Kenyans were asked to provide the GPS coordinates of their homes and give biometric data like their fingerprints, the shape of their hand and earlobes, the pattern on their retina and iris, their voice waves and their DNA data.

Failure to do so within a time frame will lock them out of government services. The system received heavy criticism for its extra-ness, and there were concerns about the security of all of the collected data (Kenya has no data protection laws), its invasiveness, and the potential for the DNA data to be used for ethnic discrimination, which is a problem there. Some have pointed out the potential for the data to be abused by unscrupulous officials as well *cough*.

So following the concerns and criticism, a three-judge bench had ruled that the system may continue, but the government cannot collect data like DNA and GPS coordinates, and government services won’t be denied to those who fail to comply.

Even in other countries that didn’t try to get everyone’s DNA data, there had been issues and controversy with the system. The UK used to keep more DNA profiles, but in 2008 a European court ruled that keeping innocent people’s DNA on record is a breach of the Human Rights Convention. The UK then deleted millions of DNA profiles and samples from its database, and tightened their DNA collection and storage ever since.

“…the retention at issue [of DNA profiles, biological samples and fingerprints] constitutes a disproportionate interference with the applicants’ right to respect for private life and cannot be regarded as necessary in a democratic society.” – part of the Grand Chamber’s ruling, from Wallace et al (2004).

As for China, it may have the biggest DNA database so far, but their methods, which borders on indiscriminate, had also come under criticism from human rights groups. So in light of all these cases, you might be wondering…

An all-inclusive DNA database may sound foolproof, but… is it a good idea?

Before we explore that question, let’s remind ourselves that it is still just a proposal at the time of writing, and the government did say that further research is necessary. But if it’s up to you, would you hand over your (or your children’s) DNA to the government and let them keep it?

Granted, a nationwide DNA database might have its benefits, but judging from the examples we mentioned above, the benefits should ideally be worth the potential controversy. For one thing, the goal is to avoid incidents of ID forgery, and since DNA samples are hard to fake, this new system sounds pretty secure, right?

Well, the keyword is ‘hard’, but it’s not really impossible. Scientists in Israel have shown that it’s possible to fabricate DNA samples, that is, to create blood and saliva samples containing the DNA that they want it to have, and this can be done even by referring to DNA data in a database. According to one of the authors of the study,

“You can just engineer a crime scene. Any biology undergraduate could perform this.” – Dan Frumkin, an author of the study, as reported by the New York Times.

Granted, some had said the technique is a bit harder than the author claimed, but regardless of difficulty, the NRD will have to consider the possibility of DNA forgery in their plan as well.

Additional measures will also have to be taken to address the concerns of privacy and human rights, which once cropped up when they came up with the DNA bill back in 2018. But perhaps above all others, as put forth by criminologist P. Sundramoorthy,

“If we don’t have honest officers, rotation or any law implemented will not be useful. From the first day of our hiring process, we need to emphasise this,” – P. Sundramoorthy, as reported by Malay Mail.

Even the most advanced technology would be useless if another NRD officer were to exploit that as well, so maybe we should address that first.

- 559Shares

- Facebook542

- Twitter1

- LinkedIn2

- Email3

- WhatsApp11