3 Malaysian “Buddhist” practices that may not actually be 100% Buddhist

- 2.8KShares

- Facebook2.6K

- Twitter20

- LinkedIn16

- Email42

- WhatsApp141

Being a multiracial and multi-religious country, Malaysia takes pride in its diverse and multicultural population. But this can also make the process of filling up government forms in Malaysia tricky. Especially with all the available (or a lack thereof) options for a religion, it can be confusing for people to identify their religious affiliation accurately on paper.

In fact, a study in 2010 showed that majority of Malaysian Chinese (83.5%) identify themselves as Buddhists. 11% consider themselves to be Christians and only 3.4% call themselves Taoists (the remaining ones are either Muslims, Hindus or Lain-Lains).

But here’s the thing, did you know that most Malaysian Chinese practices are actually not Buddhist?

When we say Buddhist, we often think of someone who prays with joss sticks or incense, burns joss papers and prays to Buddha and Guan Yin Ma. And while that definition is true in a Malaysian context, most Buddhists in other parts of the world will probably just look at us weird when we talk about these practices.

So, why is our idea of Buddhism so different from other countries? Well, let’s revisit history in ancient China…

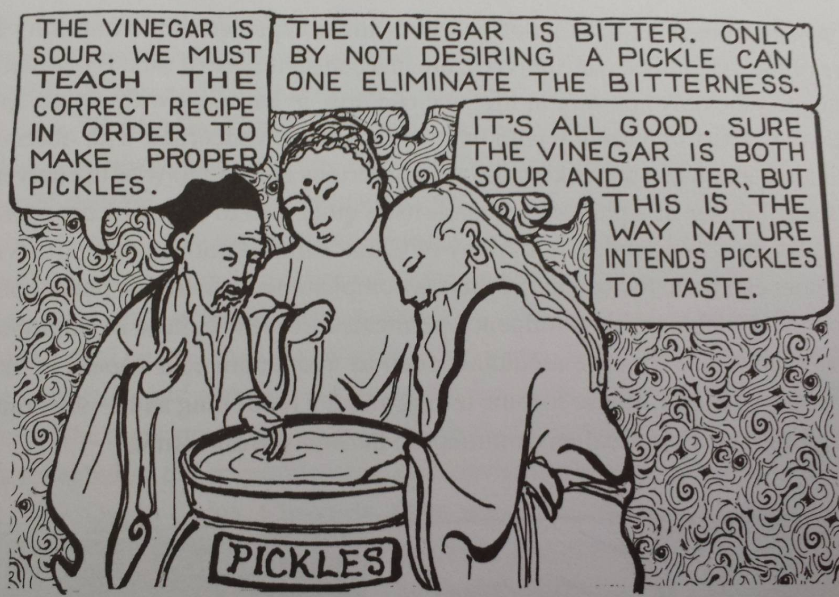

There were 3 main teachings that had greatly influenced ancient Chinese society

Not only that, these teachings have also grown to influence present day Chinese culture, which is why some people might probably find the next few terms quite familiar…

- Taoism

- Chinese philosophy founded by Lao Tzu

- about the natural flow of life, according to the Tao (imagine it as a cosmic force)

- best way to live life is to go with the flow of the Tao and accept whatever life brings you

- Confucianism

- Chinese philosophy founded by Confucius

- ideas focus on humanism and family

- central theme: ancestor worship and filial piety (respecting and obeying your parents/elders)

- Buddhism

- originated as a religion, founded in India by Siddhartha Gautama (aka Buddha)

- main goal in Buddhism is to achieve enlightenment through meditation

- 2 branches of Buddhism:

- Theravada Buddhism – Indian-influenced, mostly found in Southern Asia

- Mahayana Buddhism – Chinese-influenced, predominant in East Asia, including China

But as influential as these 3 teachings were, they never coexisted during the same time period. In fact, there were even certain dynasties where one teaching would rise to dominance because it was favoured by the Emperor while followers of other teachings would be executed.

And these teachings aren’t the only ideas that have influenced Chinese religion. There’s a reason why there are so many gods in Chinese culture and the answer to that is Chinese folk religion.

For those of you who don’t know, Chinese folk religion (aka traditional Chinese religion) is mostly influenced by folklores about gods, ghosts and spiritual beings. These beliefs came about after some Taoist leaders started to introduce different “folk” beliefs, shamanistic cults and deities into Taoism, which eventually grew to influence Chinese folk religion.

In fact, one of the main practices of Chinese folk religion is image worshipping (it’s when you worship images of real-life people as gods). Which explains why some people worship figures like Guan Yu and The Monkey King because even though they were originally characters in traditional Chinese literature, they still got deified later thanks to their heroic achievements.

But that’s just ancient China, what about Malaysia?

Most of these teachings reached Malaysia during the Chinese migration

Even though our idea of Buddhism today is a mix of Taoism, Confucianism and Chinese folk religion, the earliest form of Buddhism in Malaysia was actually Indian-influenced. In fact, Buddhism’s actually one of the earliest religions to have arrived in Malaysia thanks to the Indian traders who frequently transited the area in the 5th century AD.

The current Chinese-influenced Buddhism only emerged after some of our nenek moyangs moved here from China and started building temples and practicing Chinese teachings, which created this diverse culture that’s a rojak of various religious practices.

In fact, did you know that some Malaysian Chinese celebrations are so diverse, they’re influenced by several teachings and cultures?

1. The Hungry Ghost festival is a part of Buddhism, Taoism and Chinese folk religion

Known as the Zhongyuan Festival in Taoism, the Hungry Ghost Festival is also known in Buddhism as Ullambana. The story follows Buddha’s disciple, Mu Lian as he tries to save his mother, who’s a hungry ghost, by offering food to some monks so he can help her gain merits and reduce her sufferings in hell.

But today, this festival is known for being an eerie month where scary ghosts would wander among us on earth because they finally got a holiday from hell. And because nobody wants to cross paths with vengeful spirits, we’d burn hell money (joss papers), offer food and even host performances (kotai) for them to appease them.

But the truth is, kotais are NOT part of Taoist or Buddhist practice. Although they’re meant to entertain the spirits, the practice was actually started by festival organising committees who wanted to entertain the public and attract crowds.

In fact, the practice of burning joss papers might even be a marketing myth according to this story about a man who faked his death and got people buying paper and burning it to worship him. There’s also another folklore about an emperor who possibly started the practice of joss offerings after he burned paper and bamboo houses for his mother so she can have a home in the underworld (talk about filial piety right).

Also, this is probably when we remind you that these stories are merely folklores so do take them with a pinch of salt, alright? Now moving on….

2. Qing Ming isn’t supposed to be religious, it’s influenced by Confucian values

Once a year, we’ll hear some of our Chinese friends talking about waking up early to visit their ancestors’ graves and clean it during Qing Ming or as some of us might call it, Tomb Sweeping Day. But did you know that this tradition isn’t influenced by religion at all? In fact, Qing Ming is an important part of Chinese culture and mostly based on Confucian teachings.

It’s believed that the tradition of Qing Ming started in ancient China when a prince forced his people to mourn the death of his loyal follower after he accidentally killed him (read Cilisos story about that here). And while the initial purpose of this celebration is to commemorate the deceased, Qing Ming nowadays has become a day for us to practice the Confucian value of filial piety whenever we worship our ancestors and pay our respects.

However in the original story, the prince also enforced a no burning rule during Qing Ming (because his follower was killed in a fire). But just like Indonesia’s palm oil industry, none of us seems to be following that rule anyway since Qing Ming today is all about burning joss offerings, which is ironic considering most people actually got the idea backwards.

The original meaning of such an act is to show everyone present that all former possessions of the deceased cannot be brought along to the next life… Today, this practice is completely misunderstood by the majority of Chinese. Instead of the original meaning, paper-made models have been turned into “paper offerings” – with the mistaken thought that whatever one burns, his departed relatives will obtain in the netherworld! – Nalanda Buddhist Society.

3. There’s a temple in Malaysia that worships different gods from all 3 teachings

Ok so this is technically not a practice… but it was such an odd mix that we had to include it here. Even though the 3 teachings were unable to coexist in ancient China, there’s no stopping Malaysians from practicing them altogether, and sometimes under one roof! Built in 1645, the Cheng Hoon Teng temple in Melaka is Malaysia’s oldest Chinese temple and one of the few temples in the country that’s multi-religious.

Not only is the temple home to several famous gods from Taoism and Chinese folk religion like Guan Yin and Guan Gong, it also houses some rare deities like Confucius. Although the latter isn’t technically considered as a god in Chinese religion but in certain Malaysian temples, he’s being worshipped as a deity in education.

Also, did you know that there are Buddhist temples in Vietnam that have actually banned devotees from burning joss offerings because they believe that the practice isn’t part of Buddhist custom and joss offerings are actually meant for ghosts and not gods.

However, since Cheng Hoon Teng and most Malaysian Chinese temples aren’t 100% Buddhist, not only do they allow people to burn joss offerings, they even sell it at their counter! This just goes to show that most Malaysian Chinese practices are not limited by the influence of a single religion, but rather they’re a part of the already diverse Chinese culture.

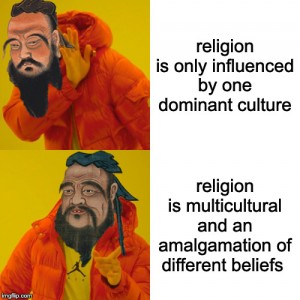

But if everything’s mixed in Chinese culture, what about religion?

Truth is, the idea of religion is so rooted in Chinese culture that it’s almost impossible to pick them apart without finding certain religious elements in a cultural celebration and vice versa. For example, it’s hard to consider Hungry Ghost festival as a cultural event without acknowledging its religious origins in Taoism and Buddhism.

And Chinese religions have come such a long way that although the 3 teachings might’ve existed as different ideas back then in China, they’re all influenced by one another today.

Which is why religion isn’t always clearly defined. More often than not, we’d notice different religions sharing similar beliefs and that’s fine. So don’t worry if you’re a Buddhist who practices Taoist customs, it doesn’t mean you have to denounce your faith or reevaluate your life. Because at the end of the day, religions are influenced by various teachings and as long as we practice them accordingly, it should be good enough right?

- 2.8KShares

- Facebook2.6K

- Twitter20

- LinkedIn16

- Email42

- WhatsApp141