Meet Dr. Wu – the Penangite who taught China how to quarantine the 1911 plague

- 19.5KShares

- Facebook18.6K

- Twitter82

- LinkedIn41

- Email140

- WhatsApp591

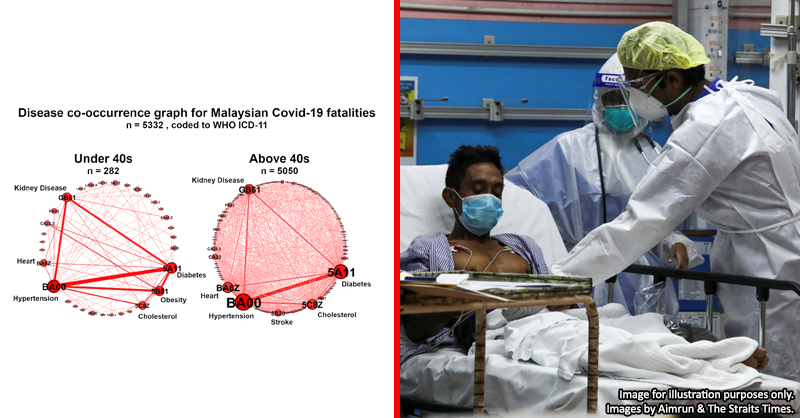

As many of you would know, the Covid-19 pandemic continues to plague the world, and even tho Malaysia is currently doing great in handling the crisis, it’s still too early to be complacent.

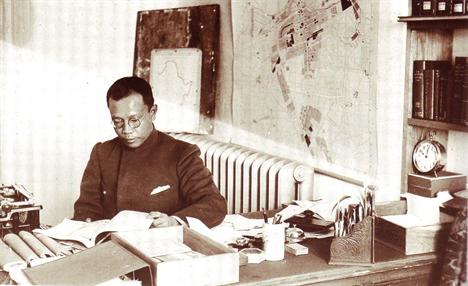

This article however, isn’t about the current Covid-19 pandemic. In fact, this is far from the first time China has had to deal with a plague, as the SARS epidemic remains in recent memory for many of us. However, there was also a time in the early 1900s, when a plague hit China, and the man who would lead the fight against this disease was a Malayan doctor by the name of Dr. Wu Lien Teh.

Heard of him? Well we definitely haven’t. So here are 5 things about Dr Wu, the man China called the plague fighter.

1. He was the first Chinese medical student to graduate from Cambridge

Dr. Wu was born in 1879 in Penang. His father was a goldsmith whose family immigrated from Taishan, Guandong whereas his mother was a second-generation Hakka residing on the island. As a young boy, his parents sent himt to study at Penang Free School, arguably the best school on the island (although SXI students may beg to differ).

Back then, going to study in the UK wasn’t as common as it is today, and one of the few ways to get there was by winning scholarships. One scholarship in particular, The Queen’s Scholarship was awarded to promising students from the Straits Settlement (Melaka, Penang and Singapore). And Dr Wu must have been a really bright student because at the tender age of 17, he won the this scholarship and earned a spot at Cambridge University.

And it seems he didn’t just study there. Like a true Asian, he whooped everybody’s butt when it came to his education.

“According to an article in the Penang Monthly by Koh King Kee, Dr Wu completed his medical degree two years ahead of requirement, and won all possible prizes and scholarships in a class of 135 students.”- The Star Online

But he definitely didn’t stop at a degree la. He eventually did his postgraduate research on Malaria at Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine. (Ross Ronald, Dr. Wu’s supervisor was himself the winner of a Nobel Prize in 1902.) Afterwards, he proceeded to study other fields (namely Bacteriology and Tetanus) at famous health institutions in Germany and France.

And when he finally returned to Malaya, the doctor became a scientist at the local Institute of Medical Research and researched the beri-beri disease, which affected thousands of Chinese tin miners. But aside from diseases, he also seemed to have a strong fascination with other things that were affecting thepeople.

2. He founded one of the first anti-dadah association in Malaya, but also had to leave the country because of it

Opium (the dried latex from the poppy plant) could be processed legally as a legit medicine and through illegal means, transformed into heroin, an addictive recreation drug. And back in the day the consumption of opium was a serious social issue in China.

It was such a big thing that when the Chinese labourers migrated to various countries in search of a better life, they brought with them their culture of smoking opium and along with it establishments known as the opium dens.

Alarmed by the widespread usage of opium among Chinese labourers on Penang Island itself, Dr. Wu founded the Anti-Opium Association. However, in his quest to rid the illegal use of opium, he ruffled some REALLY powerful feathers.

“(His fight against illegal opium usage) pitted him against powerful forces – the British colonists who approved the distribution of opium and triad-linked Chinese tycoons. He was soon framed by these connections, leading to a search and subsequent discovery of a mere one ounce (around 28g) of opium in his clinic. It was quickly regarded as illegal, although he was a fully qualified medical doctor who had used the drug to treat opium patients.”- The Star Online

And just like that, he was on the verge of being convicted as a criminal. But his achievements did not go unnoticed. The publicity brought forth by his trial gained the attention of many parties, including that of the Qing gomen in China. Taking pity on his predicament, they offered him an escape route- become the Vice-Director of the Imperial Army medical College in China. And because he really didn’t have a lot of options left, he took up the position and left Malaya.

3. He went to China where he literally waged war on a plague

“Wu Lien-teh deservedly earned the accolade. He saved millions of lives, who could have died in the deadly epidemic outbreak in the northeastern region of China.” – Dr. Wong Yee Tuan from the Penang Institute, through an email interview with CILISOS

During the autumn of 1910, news of a deadly disease reached Beijing. In the North-Eastern city of Harbin, there were reports of people who exhibited these symptoms: coughing of phlegm filled with blood, and purplish discolored skin. This would eventually be followed by death after a few days. And it was so bad that within the first 4 months of the disease breaking out, 60,000 people had died.

In December of that same year, Dr. Wu was sent there to investigate the disease, especially with the Chinese New Year season around the corner. This was because the Chinese gomen knew the risk of disease spreading all over the country when people from the affected areas started to balik kampung.

And in the first ever post-mortem conducted in China, he eventually found out that the disease was similar to the Bubonic Plague. Called the pneunomic plague, the disease was spread by cute little animals, in this case, cute animals called marmots! Worse still, the bacteria reproduced extremely quickly, which resulted in massive epidemic similar to SARS or H1N1.

Thinking quickly, he advised two measures to combat the plague:

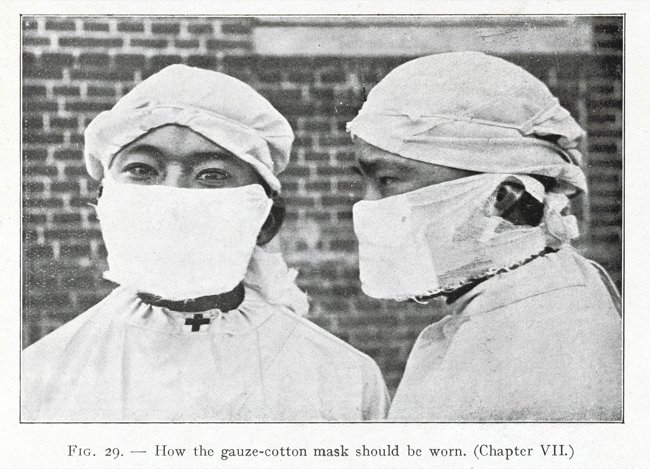

- Quarantine the affected area while making sure the others wear masks for protection.

- Cremate the bodies of those who died from the plague.

The second measure was a cultural no-no for the Chinese of that time, but it worked and plague finally ended after 7 terrifying months. Apparently just in time for Chinese New Year as well. Deja vu much?

Incidentally, there’s also the story of a French doctor by the name of Girard Mesny, who was also in China to investigate the plague. Dr Wu’s research findings suggested that the plague was spread through human-to-human contact via respiratory droplets. As such, he came up with the idea for a mask made from layers of cotton and gauze. This prototype mask of his would eventually become the N95 mask we know of today. A video exploring the N95’s creation by Dr Wu even did the rounds online, which you can find here.

However, Mesny – believing that an Asian doctor was not qualified to handle such a serious case – ignored his advice to wear a face mask when treating patients. Mesny then died to the disease in January of 1911.

As for Dr Wu, he didn’t just end a plague, he helped make sure that it would never happen again. His work with the plague not only got people calling him the “plague fighter”, he also chaired the International Plague Conference of 1911.

“Apart from this, Dr.Wu devoted many of his efforts to establishing hospitals and medical colleges and founded the Chinese Medical Society.”- Dr. Wong

His work during the plague was also what led to his Nobel Prize nomination in 1935.

4. He came back to Malaya to escape from the Japanese, but eventually settled down here again

Alas, his good life in China was to come to an end not long after his Nobel Prize nomination.

When the Japanese invaded China in 1937, no one was spared in the wake of their attack. This included Dr. Wu, whose house in Shanghai was bombed to oblivion. Realizing that the war had put an end to his scientific career in China, he decided to return to Malaya.

He opened up a private clinic in Jalan Brewster, Ipoh. There, he provided free medical treatment for those who were poor. Besides that, he gave in to his bookworm urges and helped set up the Perak Library (known today as Tun Razak Library).

Still the Japanese did reach Malaya eventually. And in the midst of all this, he was kidnapped by the communists, and also accused by the Japanese for working against them.

Still, he managed to overcome it all because he lived past World War 2, and continued to practice medicine until he passed away in 1960 at the age of 80.

5. He was a man of many talents and interests, which he used to advance humankind

By the time of his passing, it was said that Dr. Wu recieved no less than 20 honorary degrees from renowned academic institutions. These accolades included PhDs from Johns Hopkins University, Hong Kong University and the Imperial University of Japan.

As a scientist and also a researcher, he contributed massively to the field of medicine and health. Among the 92 papers published, 1/3 of them touched on the subject of plagues (not surprising), while the others were about infectious diseases, narcotics, public health and medical history. And his research papers have become a lasting legacy of his because it allowed other researchers to build upon his work.

But despite being a medical person, Dr. Wu also held an appreciation for other kinds of knowledge. For instance, between 1895 and 1905, he co-edited The Straits Chinese Magazine, a journal of arts, science and society. Due to his intense respect for knowledge and understanding, he even donated over 2000 books to Nanyang University and contributed 3000 pounds to the Royal Asiatic Society (an institute that promoted understanding between China and the West).

While Malaysians may not be so familiar with him, the medical world mourned his death

“According to Koh, Wu’s death was mourned by the international medical community, and The Times London commented on Jan 27, 1960: ‘By his death, the world of medicine has lost a heroic and almost legendary figure and the world at large one of whom it is far more indebted to than it knows.’ “- The Star Online

Oklah. So, Dr. Wu isn’t completely forgotten in Malaysia. There’s a road in Ipoh and a neighborhood in Penang named after him. In fact, one of the rumah sukan in Penang Free School bears his name.

You can even check out this documentary about the great doctor below (part 1 of 3):

Despite the gallant efforts of local groups such as The Dr. Wu Lien-teh Society to keep his name alive, it seems that many of us still don’t know who he is. Some might argue that his achievements were mostly tied to other countries, but it should be noted that he first started off serving the people of Malaya, and ended his life serving the people of Malaysia.

He was a Malaysian who dedicated his life to honouring humanity, and perhaps it’s time we return the favour by honouring him.

- 19.5KShares

- Facebook18.6K

- Twitter82

- LinkedIn41

- Email140

- WhatsApp591