5 things I learned from begging at Masjid Jamek

- 2.1KShares

- Facebook2.1K

- LinkedIn3

- Email2

- WhatsApp14

In 2014, FT Minister, Tengku Adnan Tengku Mansor, called on all soup kitchens feeding the homeless to cease operations within 3km of the golden triangle. If you didn’t know, this caused a major uproar.

Back then, I was interning at a local English daily. With this news making headlines all over the country, they had a brainwave – What about the beggars? Plus, it was Ramadhan!

My then-editor overlords decided to undertake an undercover operation at Masjid Jamek after it was reported that our Prime Minister wanted to help shelter those affected by the ban. No one had attempted something like this (thank you Google), so it was going to be unique.

The next question – Who will go undercover? Well…. INTERNS! We’re disposable!

But I wasn’t upset about it. Going undercover is something I’ve always dreamed of doing. Probably something everyone has at some point wanted to do, too. When an opportunity strikes, you’re going to grab it by the… urh. Nevermind.

So the mission was set: A crew consisting of a senior journalist and two interns will go undercover as beggars to investigate and record the syndicates that operate around Masjid Jamek. Also, to see how much each one of us can make over the course of the day. We chose Masjid Jamek for safety reasons…Our senior cameraman warned us against begging near Cahaya Suria after nearly getting stabbed by an enraged homeless man.

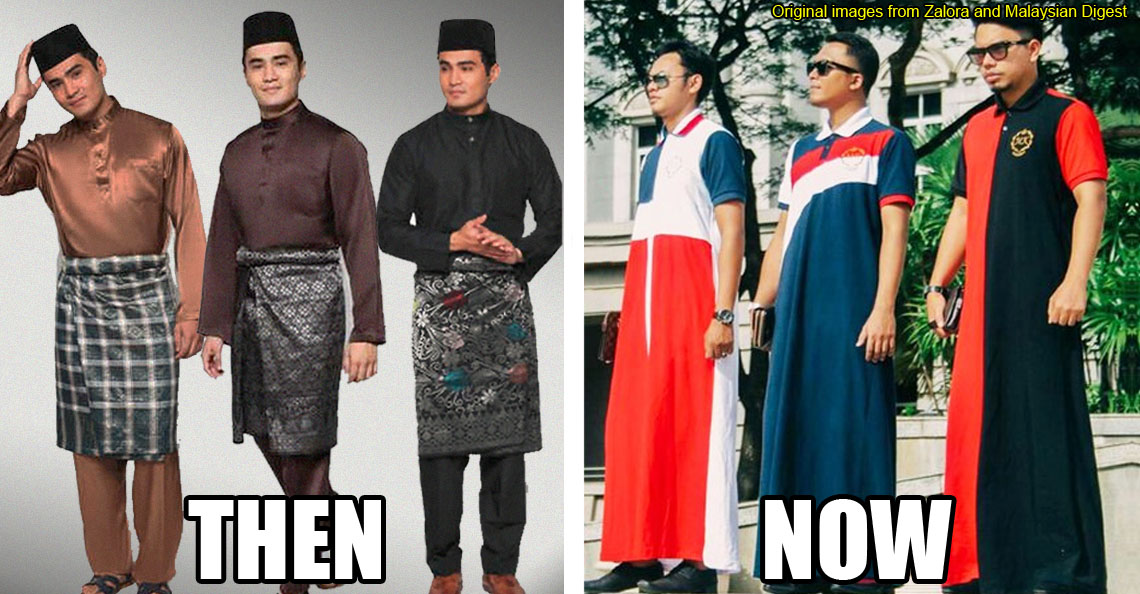

While I don’t have photos of my stint as an undercover beggar, the big photo above is the best we could come up with as an artist’s impression:

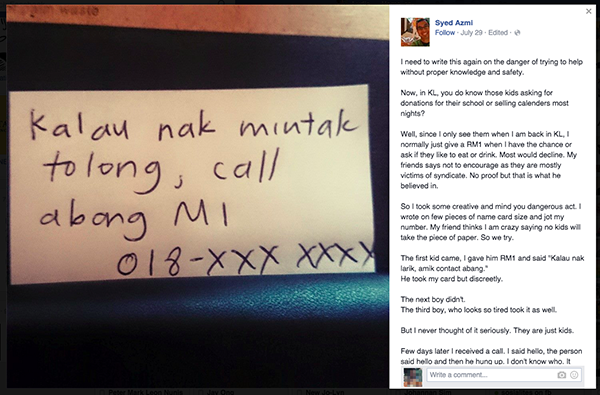

Fast forward to today, in 2015…. I’m now doing a work placement at CILISOS.MY and decided to revisit my first undercover operation with a colleague just before Ramadhan ended. Why? To suss out whether anything has changed, and to confirm my findings from nearly a year ago.

1. Ramadhan month is a beggar’s paradise

“They come to beg regardless of race or religion” – secretary of Masjid India, Ebrahim Mohideen tells CILISOS

Ramadhan, to Muslims, is a month of forgiveness, discipline, and charity. Well, mainly charity because it is one of the five pillars of the Muslim faith. And during the month of Ramadhan, it is pretty normal to see an increase in donations and charity given out by Muslims during this period.

Beggars know this.

But apparently, the begging alleys around Masjid Jamek aren’t just for Muslims, but a combination of cultures that’s more 1Malaysia than your seasonal Petronas ads.

The shock came when I saw a Chinese beggar shake his cup at the people leaving after Friday prayers. I thought this was odd, and that it must have been a one-off sighting. But, no. They are there because it’s profitable – news reports had shown that begging syndicates can collect up to RM8,000 a month thanks to ever generous Malaysians. There is also a worry that Malaysia’s becoming a haven for international begging syndicates, raking in tens of thousands of ringgit.

Regardless of race or religion, on Friday’s after prayers, you’ll find a multi-cultural set of beggars in front of Masjid Jamek and Masjid India, well, begging.

You’d never expect this at all if you think about it. I mean, come on it’s a mosque, which obviously means Muslims. Connecting the dots, you’d automatically assume even the beggars are bound to be Muslims. You’d think no money would go to those who don’t look in any way related to the faith. Even at my local mosque in Damansara, the beggars are 100% Muslims.

Seeing more than one race, most of whom dressed in no way appropriately to enter the mosque (click here for mosque guidelines), just goes to show that charity during Ramadhan knows no race or religion, and why beggars love the month so much: it’s a massive bonanza!

2. You won’t believe who gives out the most in donations

Take a wild guess.

[interaction id=”55bddd8397160885075be0ef”]

You ready for the answer?

Drum roll, please….

.

.

Foreign workers!

What we observed made us feel terrible. They are people you only ever notice in a crowded bus. They work the thankless jobs you and I never hope to ever do. They occupy an unofficial space in society which we never look twice at.

These are the people living on the fringes of our society, people we consider ‘pariahs’ and ‘immigrants’. They’re also the ones who earn minimum wage, if not less. We do not give them the respect that they deserve as human beings.

I had originally thought the Malaysian-Muslims would be the ones giving out most of the money. Why? Because they make more, obviously. Then, when I was begging in 2014, it turned out to be the other way – those with the least to give donated the most.

This coincides with the recent MaxMan.TV ‘social experiment’ where a group of Nepalese security guards donate to a beggar. The video also showed a few other locals who barely stopped to look at the beggar. This heart-warming video shows the purity of their act, as they even rejected the money offered by the beggar, even AFTER he revealed that he was an actor.

Speaking of money, of the paltry RM13 I collected during my begging stint in 2014, nearly all of it was from migrant workers. The most I received was RM5 from one migrant worker, to which I gave a stunned thank you. I limited funds from nearly everyone else. I thought this was simply because of the way I look – not within the usual definition of what constitutes a Malaysian. However, my female colleague pointed out the same thing. The bulk of her donations came from foreign workers, too. They did not discriminate.

It was touching to see their resolve to donate. They’d dig deep into their pockets in search of any spare change. Why they do it is simple: they empathize with those who have nothing.

But why? And during my revisit, I asked this very same question to the secretary of Masjid India, Ebrahim Mohideen. He said:

“These are people outside the system. They do not know how to give within the system.”

According to him, the foreign workers do not have a zakat system – a compulsory contribution paid once a year by Muslims of their total earnings. Because of this, they rely on paying to the poor directly.

He added that this isn’t uncommon among Malaysians either. Some people just don’t see the point of giving their hard earned money directly to government bodies. This is because they do not trust or see any proof that their money is having an impact on society, as it should. So they tend to do their own charity – give it directly to the people they know need it the most.

3. Most of them don’t work alone

We bet you’ve heard of begging syndicates. You’ve probably heard of the foreign begging syndicates in Malaysia that use disabled Chinese nationals as workers. Heck, we’ve even got syndicates using children as beggars.

While covering the story for the first time about a year ago, my then crew and I realised the existence of a syndicate running at the gates of Masjid Jamek. Beggars there were moving in an organised manner, almost as if they were being herded around.

Looking around we saw him, a dark, almost bald, fierce looking man watching over a group of beggars – mostly women. When I first met him about a year ago, he gave me this menacing look saying, ‘Get lost, newbie. This is our turf.’

This appears to be his MO: First, he’ll identify a kind souls who donated money to beggars near the gates. Then, he’ll prod and push his group of beggars to hound these people for donations. Rinse and repeat.

“Biggest problem we have is them [the beggars] clogging off the entrance. They jostle in front of the gate, chasing money. They also fight amongst themselves for the money.” – Secretary of Masjid India, Ebrahim Mohideen tells CILISOS.MY

On my revisit, to my surprise, he was still there, hounding about with his motley crew of beggars.

All this seems to work well, too. Every time they did this, the donator was forced away from giving to the people he originally intended the money for. This eventually causes problems, namely fights amongst beggars.

It has gotten so bad to the point that Masjid India, only a five minute walk from Masjid Jamek, also another beggar hotspot, has had to employ RELA to maintain order on Fridays.

4. Different people get different donations

Poll time again!

[interaction id=”55bddca797160885075bd794″]

Well… The correct answer is…. We’ll let you know later. But for now, we’ll tell you that women beggars generally get more money than men.

This might sound sexist, but from what we experienced that day, it works. Neither I nor my fellow male colleague were able to collect anything more than RM13. Our female colleague, who was draped under a crummy tudung at the corner of the LRT station, collected three times as much!

Pity is a very strong emotion to play on, and it appears they know this all too well. But you know what’s even better than one woman?

You guessed it: woman + CHILDREN.

From our observations on that day, we found that women accompanied by children (babies included), were being given large chunks of the donations.

We also observed a wheelchair-bound woman and man. While the man attempted to sell tissue papers for donations, the woman, accompanied by whom we assume is her husband, simply thanked those who donated to her. No real transaction occurred. In the end, we gauged the overall level of donations were greater for the woman, whose container was brimming with money, compared to the man.

Back to the poll – who wins? According to our observations, woman+child takes the cake.

5. Everyone has a different reason for ending up begging

Not everyone begging on the streets does it because it’s an easy way to make money. During my time as a beggar, my colleague interviewed Hani (not her real name), a 50-something year old wheelchair-bound beggar at the entrance of Masjid India. She opened up to my colleague about why she was forced to work on the streets for a living. Hani said her life back home in Ipoh was unstable, with her family not being able to afford living having her around.

So Hani decided to move to KL to find a job. Having looked around, she was unable to find any jobs. She decided to sell tissue papers around KL to make ends meet – it seemed like a reasonable job, and the money she’d make is halal. When we asked Wani about her children, she dismissed them by saying they didn’t really care for her anymore and she had no plans of going back to them.

This story of abandonment isn’t uncommon among the people we talked to. Most had dark pasts or were duped into coming to KL with job offers.

But there is a silver lining. In most cases, when it comes to beggars at least, we have this tak apa lah mentality. However, here’s where things change for the better.

While I was begging last year, I was scolded by a bearded 50-something-year-old Pakistani uncle. What happened is, while I was standing around under the drizzle begging, I heard a voice calling for me. When I turned to face it, this uncle motioned for me to come to him. He asked me where I was from. Remembering that I was undercover (this part hurt) I told him I hailed from Karachi, Pakistan.

He looked at me intensely, then started scolding me. “What are you doing here? You’re young, healthy, and able bodied, and yet you’re begging?! Who put you up to this?” I had no reply. “Look at me! I am in my late 50’s and I work hard for a living. This money you make is not halal.” I said I can’t find a job here. “You can go work in the many restaurants around here! There are so many hiring nowadays! Stop making excuses! Now go away. I need to do my business.”

That session has stuck with me ever since. He was right to take me to task for what I was doing, and it hurt that I had to lie to his face during Ramadhan. But it also highlighted an important point: there are people who care. During our revisit, the one thing on my mind more than anything was meeting this uncle again. I wanted to tell him the truth, but it never happened – he wasn’t there.

Is there a solution?

What do the people who have to live with it feel on a daily basis, and is there a legitimate solution to this problem?

Elsewhere, even the most modern of countries seem to have problems resolving this issue. Norway’s attempt to criminalise begging and to fine those who help them backfired. Other methods of solving the issue come in the form of an advisory, calling on people to not give to beggars and to instead donate to local charities. Not a bad idea, but it doesn’t necessarily solve the problem.

Knowing that the most innovative solution thought up is banning their source of food is disconcerting and unhelpful. If anything, we need a permanent solution to this problem. Ku Nan’s ideas might seem like the next logical step to him economically, but it was an inhumane decision to take from the get go.

That’s the thing, we do not treat these people like human beings at all. ‘Sampah masyarakat’ is a term we often use to define them, but is that in any way accurate? Our blatant disregard for their well-being, simply because they live on the fringe of our society makes us no better than the syndicates that abuse them.

But the one thing I came to realise is we, the people, are the first line of defense against these syndicates and their abuse. What the Pakistani uncle decided to do is what we, too, need to do as well. We need to care. We need to be able to take time from our busy day and take to speak to these people, help them where necessary. We need to learn to distinguish between those being used by syndicates and those who legitimately need our assistance.

This does not mean that we can forgive and forget the lax in enforcement. We still do not have laws in place to combat syndicated begging. Children are still being abused for profits. Enforcement standards need to be raised.

Would I go undercover again? That’s a question I asked myself during the revisit this year. The obvious answer is no.

My mother laughed at the idea of me actually going undercover when I told her, saying that if people recognised me it’d be an embarrassing encounter.

She’s right. They say to learn about someone’s life, you need to walk a mile in their shoes. As much as I enjoyed the experience, being given the opportunity to dive into someone else’s world, the idea of actually existing in those conditions is tough to swallow. The idea of people looking at me, judging me for the way I dress and for what (at least for that day) I did for a living was soul-crushing. One day’s enough.

Through this experience my eyes were opened to the needless suffering of these ‘others’. What I experienced might only be the tip of the iceberg. But the one thing I can say for certain is that we, the people, are the first line of defense against these syndicates and their abuse. We need to learn to distinguish between those being used by syndicates and those who legitimately need our assistance. We need to be able to take time from our busy day and speak to these people, help them where necessary.

What the Pakistani uncle decided to do is what we, too, need to do as well. We need to care. So do not judge a book by its cover. Likewise, do not judge a person by the clothes they wear.

*Additional reporting, images and visual work by CILISOS.MY interns Letitia Lim and Muhd Adib

- 2.1KShares

- Facebook2.1K

- LinkedIn3

- Email2

- WhatsApp14