6 interesting facts about Malaysian wildlife you’ve probably never heard of

- 147Shares

- Facebook121

- Twitter5

- LinkedIn6

- Email6

- WhatsApp9

Say you have to design a logo involving a Malaysian wildlife. What animal would be featured on it? If you say tiger, tapir, or orangutan, then we’re sorry cause ya basic.

It’s not your fault, really, because those are probably the animals getting the most conservation attention, so more effort had probably been made to raise awareness about them. But this International Day for Biological Diversity, let’s shine a spotlight on the other interesting yet less talked about animals roaming our rainforests. Starting with…

1. This uncommon animal, which may smell like popcorn

That frazzled-looking racoon creature is known locally as the binturong (Arctictis binturong), aka a bearcat. Despite the name, though, they’re neither bear nor cat: binturongs are viverrids, a group of cat-like carnivores that include civets. Even among this uncommon group, binturongs stand out due to several things: they have muscular, prehensile tails that can support their body weight, it’s the females that are dominant in their species, and they are mainly omnivorous despite their carnivora classification, among other things.

Viverrids rely on scent for communication, and many have scent glands near their rear ends for this purpose. A binturong is no exception, and interestingly, their scent may smell a lot like popcorn. One of the chemicals they produce – 2-acetyl-1-pyrroline – is a common product of the Maillard reaction, which is what happens when you brown food and caramelize sugars. So if you suddenly smell popcorn in a forest, it’s probably a binturong and not some concession stand pontianak.

If you smell pandan, though, it could be another viverrid: the musang pandan (Paradoxurus hermaphroditus), aka the Asian palm civet.

2. One of these birds isn’t actually Sarawak’s state bird

Both these hornbills may look the same, but sharp-eyed readers will notice a few slight differences. The one on the left is the rhinoceros hornbill (Buceros rhinoceros), the state bird of Sarawak, while the one on the right is the great hornbill (Buceros bicornis), which can’t normally be found in Sarawak. Telling the difference is easy once you know what to look for: great hornbills have yellowish necks and white bands on their wing feathers, while the rhinoceros hornbills don’t.

Another obvious difference is in the ‘horn’, or more correctly called the casque: the rhinoceros hornbill’s casque usually protrudes outward more, often curving upwards. Interestingly, the casque’s function in hornbills is unclear. Some theories include casques being a sign to other hornbills that it’s an adult male hornbill of status (hornbill casques develop after sexual maturity), as weapons when fighting other hornbills mid-air, or even as a counterweight/reinforcement to make their huge bills more manageable/stronger.

But perhaps the most interesting theory is that it’s a sort of echo chamber: the hollow casque, together with other structures in the hornbill’s head and neck, is believed to amplify their calls.

3. This cute mammal packs a venomous bite

This teensy primate is known as the slow loris (Nycticebus coucang), or the kongkang locally. For some reason, people believed that the slow loris has supernatural qualities, and its body parts are often used as medicine or curse ingredients in Southeast Asia. Some cultures believe that they’re bad luck, killing them on sight, while others (like in rural Indonesian Borneo) believe that they’re gatekeepers to heaven, with each person having a personal slow loris waiting for them in the afterlife.

But perhaps the most unexpected thing about the slow loris is that it’s one of the few mammals that are venomous. Threatened slow lorises will enter a defensive pose that looks much like a boxing pose, where it will lick up venom from glands found near its elbows. This venom is mixed with its saliva, and it’s either applied to the fur around its head or neck or delivered through a bite. While it seems to not be deadly to people usually – unless you’re allergic, in which case you can go into anaphylactic shock – the bite can be excruciatingly painful, and the effects can be quite serious.

Sadly, these cute slow lorises are victims of the illegal pet trade, and many met their ends in the hands of pet traders, who may cut off the lorises’ teeth to prevent them from using their venom-laced bite.

4. A pangolin’s scales are just made of the same material as our nails

Malayan pangolins (Manis javanica) are also known as tenggiling in Malay. Fun fact: their English name is also technically Malay, as it’s a corruption of the word ‘pengguling’, meaning one who rolls. Both names are a reference to their habit of rolling themselves into a ball when threatened, shielding their soft underparts with their tough, scaly exterior. Perhaps surprisingly, their hard scales are made off the same basic material as hairs, nails, and even a rhinoceros’ horn: keratin.

While these scales protect the pangolin’s body throughout its rough routine of digging and burrowing, they’re also the reason why pangolins are the most trafficked animal in the world. There is a demand for pangolin scales in traditional medicine, driving pangolins to extinction despite various research finding virtually no real medical benefits from them – it’s just keratin, after all. On a less distressing note, pangolins don’t have teeth: they swallow tiny stones to help grind the insects they eat.

5. Sun bears may ‘talk’ with each other using their faces

Not to be confused with the moon bear, the sun bear (Helarctos malayanus) is probably most well-known for their yellowish/creamish chest patch, which is flashed to intimidate enemies when threatened. A generally shy and timid boi unless provoked, sun bears are known to be the kind of bear who spends a lot of their time on trees, sunbathing and slurping up insects and honey using their incredibly long tongues for a snacc.

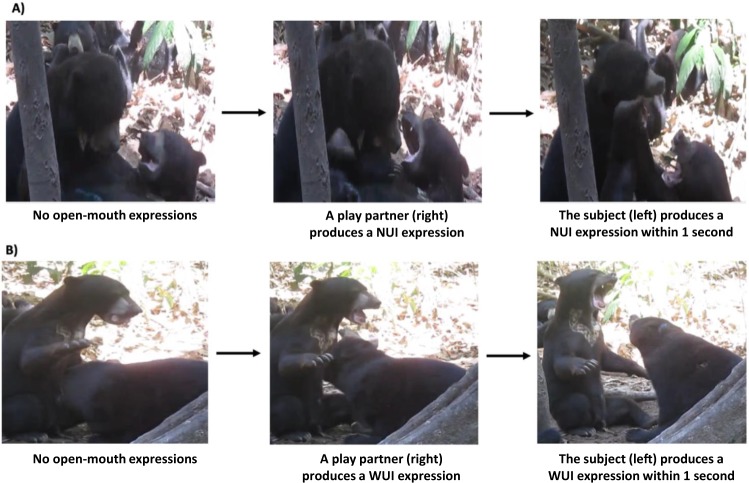

Since they’re generally solitary, it’s kind of surprising when some researchers noticed that sun bears use a form of facial mimicry to communicate with each other. Facial mimicry – copying the facial expression of another individual – is generally seen in primates and some domesticated dogs as a form of nonverbal communication, and sun bears may be the only bear species known to use it so far. It was observed that when playing with each other, sun bears may exactly match the facial expression of another bear as a signal to continue playing, or as an agreement to transition from gentle play to rougher play.

6. Orangutans build new, sophisticated nests almost every day

Okay, so this is one of the popular kids, but forgive us because even popular kids have layers. The orangutans (Pongo pygmaeus) are known to be one of the more intelligent great apes, having been observed to efficiently use tools and communicate to each other about past events, among other things. Like other great apes, orangutans also build nests, and it seems to be a learned behavior: orangutans who spend time around nest-building adults tend to start making them sooner. These nests are usually flat platforms on trees that are commonly only used once, although in some cases orangutans may reuse them or add improvements to it.

To build a nest, an orangutan will choose a suitable tree and start making the foundation. This is done by pulling some bigger branches towards and under themselves and uniting them at the same point. Then they will make a sort of mattress by pulling in smaller, leafier branches towards the foundation. Once everything is in place, the orangutan will lock everything together by standing on the structure and braiding the branches together. As a final step, the nest may be customized by adding certain features like pillows, blankets, a roof, or even a second layer – a bunk nest, if you will.

We don’t know about you guys, but we’ll definitely be keeping the mental image of orangutan snuggling in their bunk beds to get us through this week.

- 147Shares

- Facebook121

- Twitter5

- LinkedIn6

- Email6

- WhatsApp9