The Penang gang war in 1867 that was started by… a thrown rambutan skin

- 365Shares

- Facebook288

- Twitter9

- LinkedIn7

- Email10

- WhatsApp51

When we think of Penang, we usually think of food, street art, history, bad driving, food, and, well, more food. It’s a pretty chill place, and probably the last place you’d think of for something, like, say, a riot.

But believe it or not, Penang has been the center of more than one riot in Malaysian/Malayan history. Probably the most notable one is the 1967 Hartal riot, which we covered in another article. However, there was one other not-so-famous riot exactly 100 years earlier, which was a violent gang war caused by a dispute between the secret societies of Penang.

The Chinese ‘Kongsi’ groups were formed for protection

Hue or ‘secret societies’ or what we now call ‘kongsi’ were initially created as a form of mutual aid, as well as a check against injustice. The White Lotus, one of the earliest known Chinese secret societies, are largely credited with the downfall of the Mongol-run Yuan dynasty.

And when the early Chinese immigrants to Malaya first arrived, similar groups were formed to offer protection to their own in a foreign land.

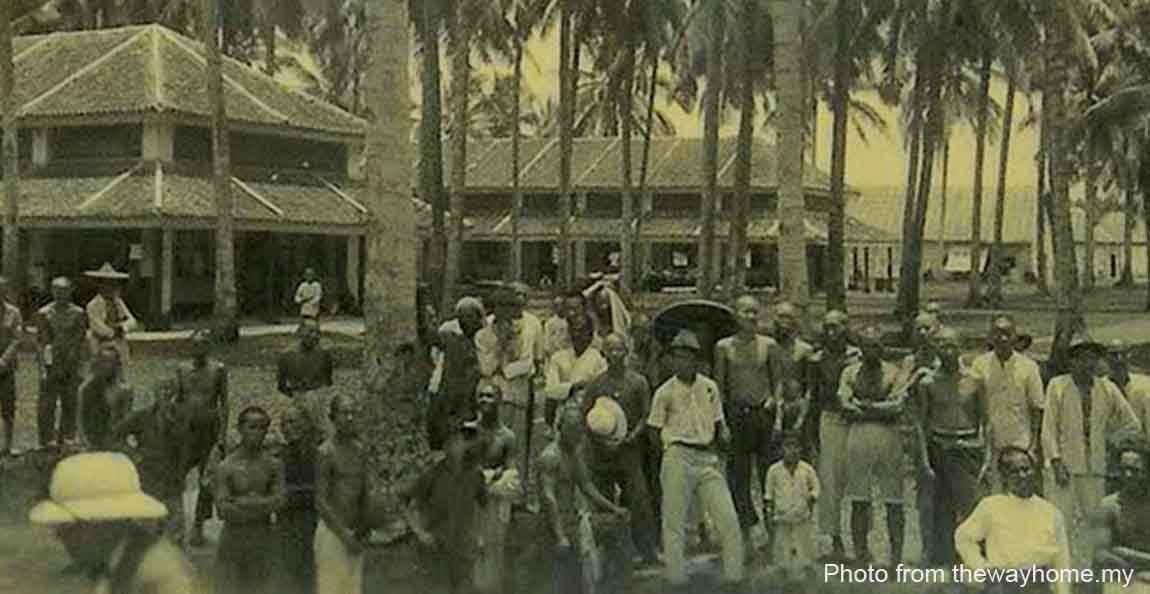

When the East India Trading Company set up a trading factory in Penang, more and more immigrant workers were attracted to the island, most notably Hokkien migrants. In the mid-19th century, two major rival kongsis, namely the Cantonese Ghee Hin and the Hokkien Tua Pek Kong (Kean Teik Tong) established their dominance in Penang.

Around the same time, the local Malays started to get in on the act with their own creatively-named secret societies, namely, the Red Flags (led by Tuan Chee, allied with the Tua Pek Kong), and their rival group White Flags (led by Che Long, allied with the Ghee Hin). These alliances were further strengthened due to how close their places of worships were –

- Masjid Pintal Tali (White Flags) and Meng Eng Soo Temple (Ghee Hin) and;

- Gat Lebuh Acheh (Red Flags) and Khoo Kongsi (Tua Pek Kong).

And these guys were legit BFFs to the death; just check out this cute Boria song which describes how the Red Flags and Tua Pek Kong were united in their hate of the Ghee Hin:

Kampong Che Long, Khian Teik kongsi (Che Long’s Village, Khian Teik kongsi),

Taukeh, Ghee Hin sudah mati (The Ghee Hin Leader is dead),

Tiada tiru, sendiri reka (We do not follow, we are independent),

Kampong Che Long, Kompani Kita (Che Long’s Village, Our Company)

– as quoted by Khoo Su Nin, from Hidden Hands and Divided Landscapes: A Penal History of Singapore’s Plural Society

Pretty wholesome for two groups who actually started out as enemies.

During a quarrel, the first shot fired was… a rambutan skin

Sooo yeah, it might sound like a joke at first reading, but trust us, it really isn’t.

After few confrontations during a 1865 Muharram procession in Singapore, in which the Red Flags were accused of corrupting police into persecuting the White Flags, tensions between the Reds and Whites were already high. Meanwhile, their allies Ghee Hin and Tua Pek Kong got into a conflict regarding tin mining rights, among other business dealings.

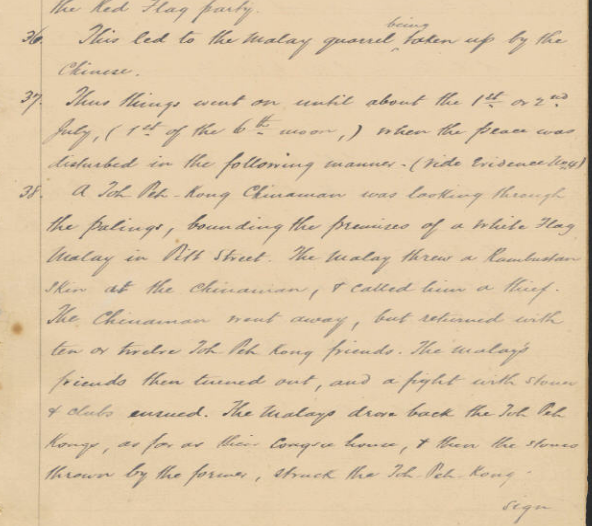

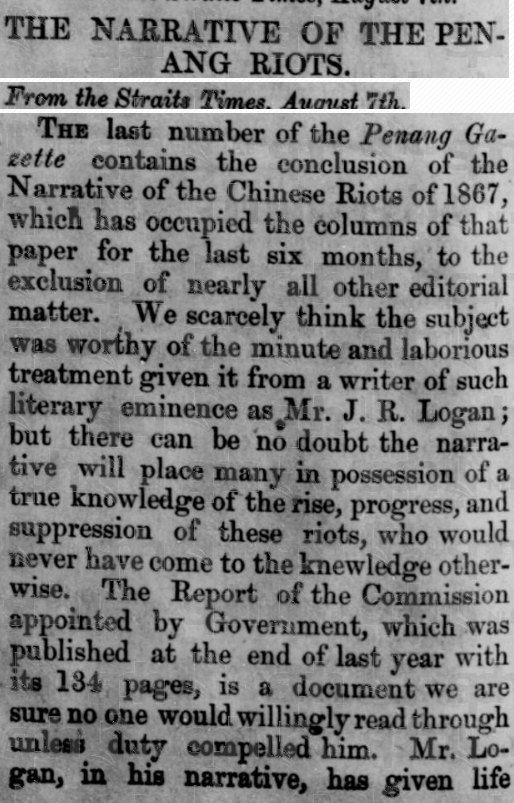

Incidentally, the 1867 Penang riots would occur during Muharram as well, and it all started with a rambutan skin and a false accusation. According to the Report of the Commissioners Appointed under Act XXI of 1867 to Enquire into The Penang Riots:

“The Malay threw a Rambutan (a Malayan fruit) skin at the Chinaman, and called him a thief. The Chinaman went away, but returned with ten or twelve Toh Peh Kong friends. The Malay’s friends then turned out and a fight with stones and clubs ensued. The Malays drove back the Toh Peh Kongs, as far as their Congsee house, and then the stones thrown by the former, struck the Toh Peh Kong signboard, upon which the Toh Peh Kongs turned out in great numbers, and fire-arms are said to have been used. The Police interfered, and succeeded in putting a stop to the disturbance for the time.”

But that was not the end of it; in fact, it was only the start. On a Monday morning at 8 o’clock, the Tua Pek Kong launched an attack on the Ghee Hin. Fights were sparked on Beach Street, Bishop Street and along China Street, and these guys meant business.

Rioters organized and armed themselves with sticks, spears, knives and muskets, setting fire to the attap houses as they advanced through town. Even the Sepoys (Indian soldiers serving the British) were fired on, and a Havildar (Sepoy Sergeant) was killed. Some society members even fired small cannons from the rooftops!

Worse, the British colonial government were totally unprepared

The misfortune of handling the fiasco fell to the freshly-appointed and inexperienced Lieutenant-Governor of Penang, Colonel A.E.H Anson. Besides that, the Brits’ main artillery battery, usually available at Fort Cornwallis had been shipped off to Rangoon, while their main Sepoy detachment had been sent to the Nicobar Islands.

Despite these setbacks, the authorities still had a number of Sepoy and policemen aided by European and Eurasian volunteers, who were deployed to protect public buildings.

Meanwhile, the death toll was rising fast, and the town was being engulfed in flames. Just check out the description of the carnage in this newspaper clipping:

“…stray shots were hovering about all day and incendiarism became rife, houses were set fire to, in some cases their inmates shared the same melancholy fate; we saw one body—or rather the remains of one—in cinders, the fire-engines were with difficulty brought to play on the burning houses under a guard of special constables.” – as quoted from Sydney Morning Herald (16 Sep 1867)

Barricades had been erected outside the Khoo Kongsi, the headquarters of the Tua Pek Kong, where some of the fiercest fighting took place – it is said that bullet holes can still be seen in the surrounding shops and houses. The greatest violence is said to have occurred on and around Pitt Street (today known as Jalan Kapitan Keling), with countless men on both sides ending up wounded or dead; and even British troops and special constables were being indiscriminately fired upon.

It was at this point that the British government hauled up their own six-pounder cannons into the streets to fire back at the rioters. The square and street the British fired into were later named Cannon Square and Cannon Street respectively after the event. All in all, the city was paralyzed for 10 days, before British reinforcements from Singapore arrived to finally put an end to the riots.

In the aftermath, each secret society was fined $10,000, and the leader of Tua Pek Kong, Khoo Thean Teik sentenced to death (later commuted to life, but he was released after 7 years), while other leaders were deported to China. However, much like with Khoo, many of the sentences were commuted by the Governor, and the deported leaders were allowed to return to Penang. This move was derided as being too lenient, as it appeared to set the stage for future riots on the island:

“The return of this man (Boey Yoo Kong, Ghee Hin secretary) to the Settlement is a direct insult to Government and an open challenge to the Toh Peh Kongs for another fight which Tan Teck’s expected return will expedite… with their previous precedence as heads of the two great rival Chinese societies, and the amiable hatred which exists between these men, there is no longer peace for society or security or life or property.” – ‘An European’, as quoted from The Straits Times Overland Journal, 13th August 1869.

And these concerns appear to have been justified; unrest in Penang continued to escalate for the next twenty years, and by 1888 the situation was so bad that rioters were attacking Europeans and other communities. The subsequent riots were described as ‘an organized resistance to the law of the land’.

Today, the sites of the 1867 Penang Riots have become popular tourist attractions

Although the 1867 Penang Riots are a thing of the distant past, the event has been immortalized via a signboard and a street mural in George Town. It’s also the subject of a play by Liver & Lung Productions, entitled ‘Malaya Relived: The Penang Riots’.

The event was not a happy one by any means, but it’s amazing how well the story and locations involved have been preserved. The Khoo Kongsi, Acheen Street Mosque, Cannon Street, Cannon Square are all still functioning buildings and streets that can be explored today, and are definitely worth checking out during your next trip to Penang (especially now that borders have reopened).

- 365Shares

- Facebook288

- Twitter9

- LinkedIn7

- Email10

- WhatsApp51