Estate workers can be evicted tomorrow and there’s nothing they can do about it

As a true anak Malaysia, chances are you’ve grumbled about housing at some point. Rent is ridiculous, buying feels impossible and even with two incomes most of us are just trying not to drown in debt. So when you hear about estate workers demanding permanent homes after retirement, the knee-jerk reaction might be… Eh? Everyone else also can’t afford a house, so why are estate workers making it sound like a bigger deal?

And that’s a fair question.

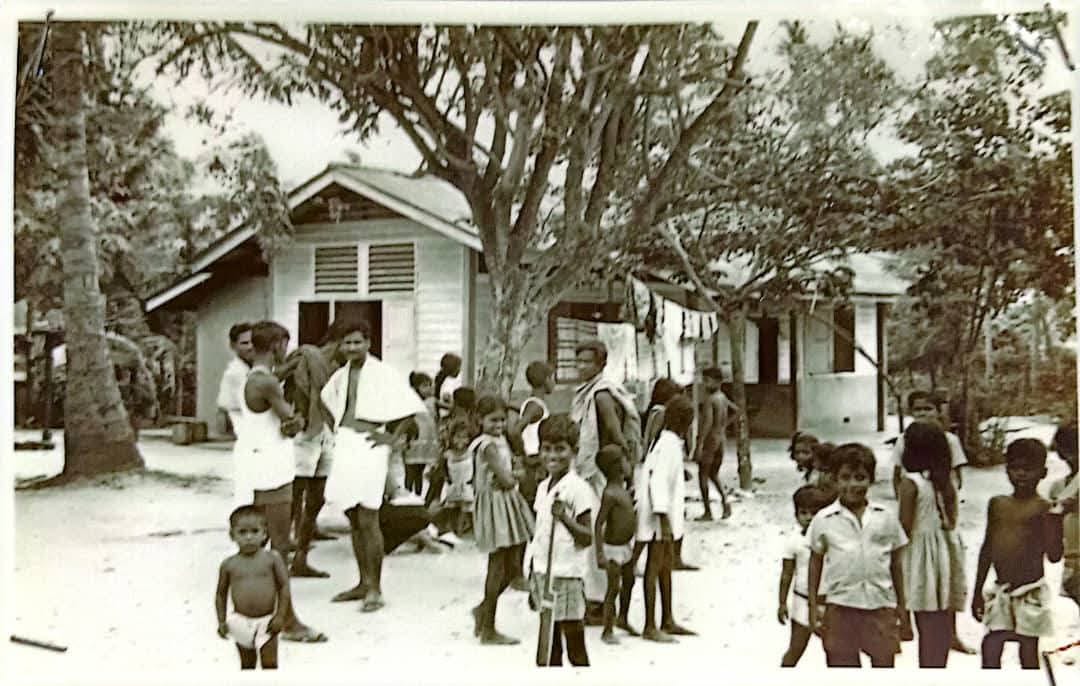

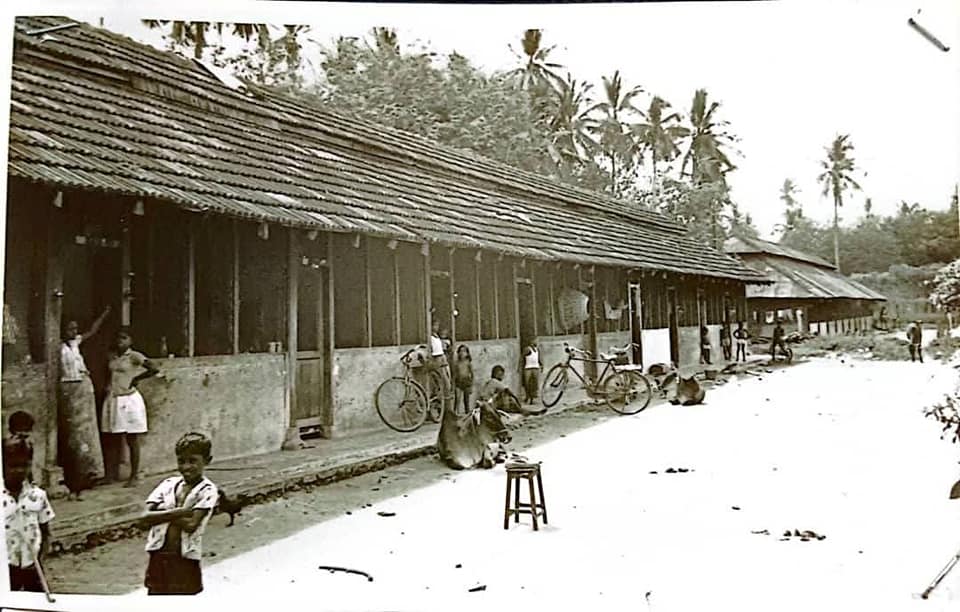

Cos technically, estate workers do get housing. But those rows of quarters you see in plantations aren’t actually theirs to keep, rather they come with the job. The moment someone retires, gets retrenched or the land gets sold, the house goes back to the company. At first glance that might sound like any other job perk but here’s the difference – entire families who’ve lived there for generations can suddenly find themselves with nowhere to go.

And it hits harder when you remember how this community even came to be here. Years ago, their grandparents were shipped in from India to clear and work the land, often in conditions nobody else wanted. The wages were low and the work was pure hard labour. Survival often meant whole families pitching in, which also meant kids missing out on school and getting stuck in the same cycle. Generations went by and many were still tied to the estates with no real way out.

So when a hundred or so of them marched to Parliament on August 13th, they were really only asking for something simple. After a lifetime of keeping Malaysia’s plantations alive, they just want a roof that doesn’t disappear the second the job does.

Thing is, the government actually tried to sort this out as far back as 1973

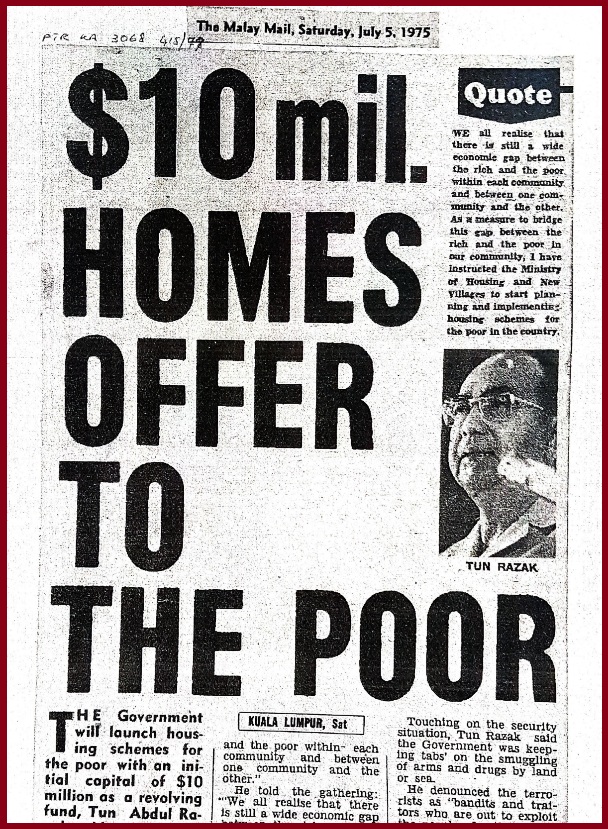

You might be surprised to know that this whole fight for estate workers’ housing isn’t new at all. In fact, it goes all the way back to 1973, when Tun Abdul Razak (that’s our 2nd PM and Najib’s dad to all of you who flunked Sejarah) rolled out what was called the Workers’ Own Housing Scheme.

On paper, it sounded like a game changer.

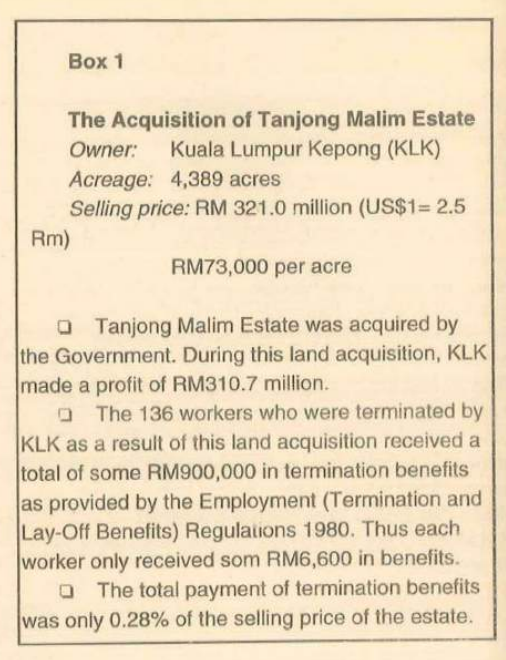

Estate and mine owners were supposed to set aside a portion of land to build terrace houses for their workers, and the workers would then pay for them in instalments i.e. through deductions from their monthly salaries. The government even set aside a RM 10 million special fund under the Third Malaysia Plan to get it rolling. A few projects in Kedah, Perak and Selangor used that money but after that, many estates just pushed workers into taking bank loans instead.

“The first and second projects in Batu Pekaka Estate in Kedah used RM5,000.00, and a second project in Dowanby Estate in Perak used RM7,500.00. But in the third project in Tennamaran Estate, Selangor, RM11,500 was used of which the workers themselves contributed RM3,000.00 which was deducted from the salary of workers by the estate management (RM50 per month).

The other projects in Sungai Buloh Estate and Glemmary Estate did not use the special fund and the workers were availed a loan of RM25,000.00 from the commercial banks. The Kamasan and Raja Musa Estate Workers housing scheme was also implemented through bank loans,” – excerpt from People’s Service Organisation (PSO) via Malaysiakini

Groups like the People’s Service Organisation (PSO) tried to help workers make sense of these agreements while also questioning what happened to the rest of that cash. Because in reality, the scheme barely made a dent. At most 33 out of the roughly 1,000 estates in Peninsular Malaysia got houses. But why so few?

If you think its something to do with the law, then you’re absolutely right, you beautiful genius, you. It all comes down to the fact the scheme was never written into an akta. It rather depended on employers’ goodwill, which surprise surprise, wasn’t exactly forthcoming. And because it wasn’t legally binding, workers were left at the mercy of whoever owned the land. And that took a pretty cruel turn when…

Rampant redevelopment bulldozed estate workers out of their homes

Fast forward a decade or two and plantations were no longer just being used for rubber and palm oil. Many estates, especially around Klang Valley, were sitting on land far more lucrative as commercial hubs. So like it or not, estate workers had to give up their homes.

But what got completely ignored in all this was the idea of the estate universe.

You see, over time, estates grew into whole communities. You had rows of quarters for families, plots of land to grow vegetables, goats and chickens roaming around, temples for prayer, schools for the kids, even toddy shops if you wanted to kick back for a bit. Some estates were so self-contained that families could go their entire lives without ever really leaving the boundaries.

“And this is not just confined to estate workers. Logging companies and implementers of major dam projects don’t realise or don’t want to recognise that when they displace a whole group of people from land on which they have lived for generations, they are, in effect, destroying the only universe that these people know,” – via FMT

Beyond just a workplace, it was home, culture and identity rolled into one. Kids grew up there, friendships and marriages happened there, generations carried on traditions there. In many ways, estates functioned like small towns that just happened to sit on plantation land.

So when redevelopment rolled through, they were really ripping apart an entire social fabric. On top of their homes, workers basically lost their sense of belonging. Imagine being told that the kampung you, your parents and your grandparents grew up in – the only world you’ve ever known – was suddenly gone because the land was “more valuable” as condos.

And where was the government in all of this, you ask?

Well, gomen did notice the fallout, but their responses were half-hearted

Selangor, for example, tried in 1991 to encourage estate owners to build permanent housing for displaced workers. Like the Tun Razak scheme before it tho, the policy was never mandatory so most companies just shrugged it off and carried on cashing in. And while permanent housing was supposed to be the obvious solution, some cases took a different turn with workers and their families moved into temporary housing while waiting for their real homes to be built.

You might think that sounds like a fair compromise but really, it was just a cop-out. Take what happened in Taman Rimba Kiara, where estate workers from Bukit Kiara were moved after the government bought over their land. In 1982, they were placed in wooden longhouses that barely passed for homes under the promise that it would only be temporary. But 43 years later, 98 families are still there, as shared by Sivakumar, a resident of one of those longhouses, in an interview with BFM.

Which brings us to the next big attempt at a fix.

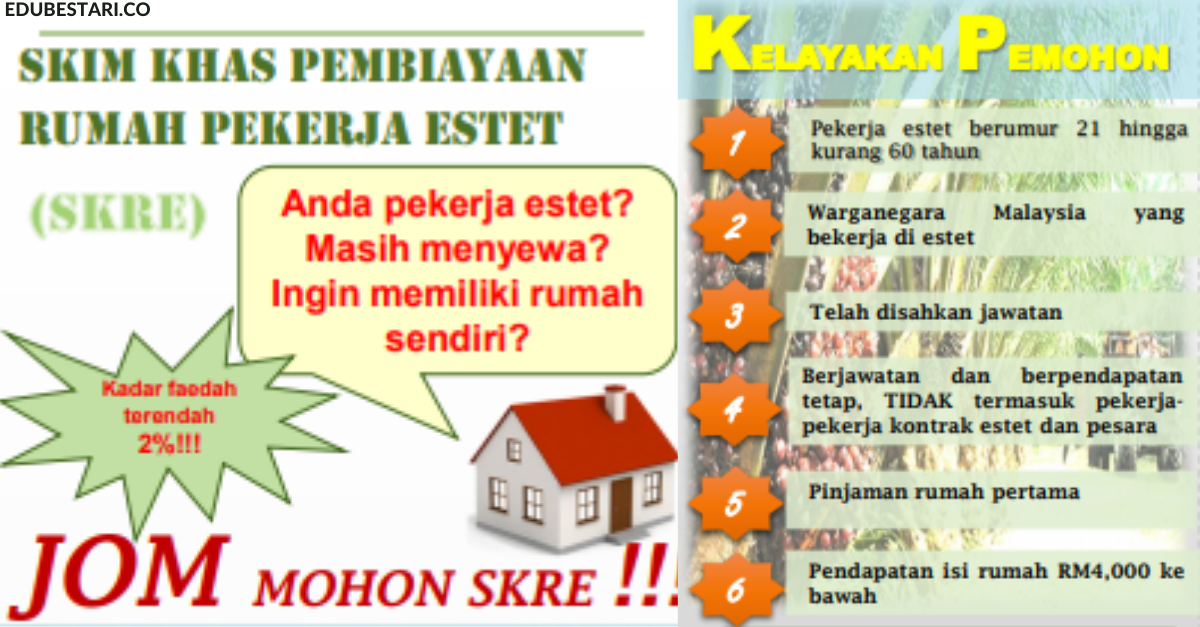

Sometime in the 2000s, the government parked RM50 million into a revolving fund. The scheme was called Skim Khas Pembiayaan Rumah Pekerja Estet (SKRE) and it was offering cheap 2% loans of up to RM150,000. This percentage was roughly half the market rate back then. So in short, whether it was buying a new house, a sub-sale unit or even building on family land, SKRE was supposed to make home ownership possible for estate workers.

But the numbers tell on themselves. After more than a decade, barely 300 workers ever used it. Because even a ‘cheap’ loan still meant coughing up around RM500 a month for 35 years. You might shrug that off as half your KL rent, but if you’re an estate worker whose entire pay packet is already swallowed by basic expenses and the occasional clinic visit, that RM500 might as well be Mount Everest.

So in practice, most workers couldn’t even afford the aid. SKRE still exists today but the situation hasn’t changed much. Either the houses are too far, too pricey, or simply out of reach given the workers’ wages. Meanwhile, some RM35 million of the fund is just collecting dust in the bank. And if we really dig into the issue of those wages…

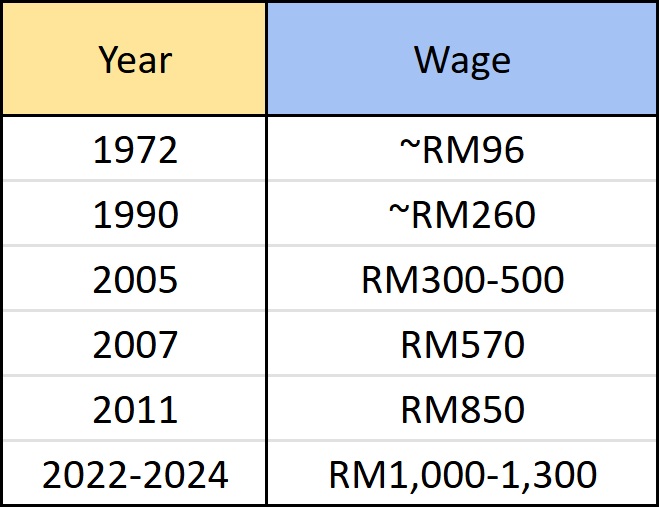

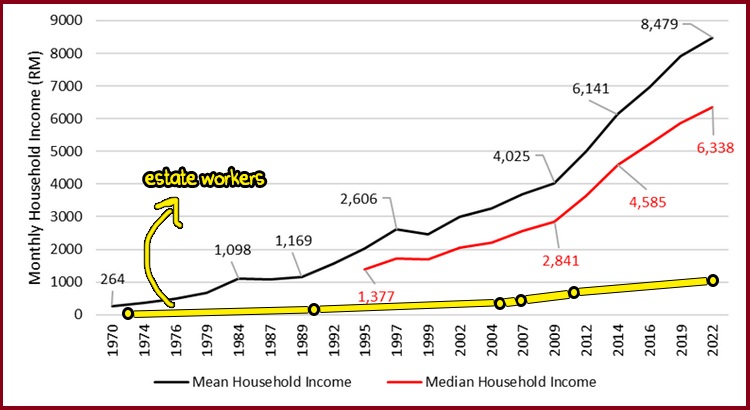

The estate wage system was designed to keep workers poor

For most of their history, estate workers weren’t even on monthly salaries. They were stuck with a daily wage system which meant if it rained, there was no work. If trees were being replanted, there was no work. So on top of their income being low, it was volatile as heck.

Plantation giants like Guthrie (before it got merged) and Sime Darby defended this by saying wages should follow productivity. But productivity in estates depends on things workers couldn’t control like global prices, fertiliser supply, even the weather. Imagine your boss docking your pay because of bad weather. That was estate life.

Now, you’d think the government might step in with rural development help. After all, farmers had FELDA, fishermen had support schemes, even paddy planters got subsidies. So why were estate workers left out? The official reason was that estates were private sector business, so housing and welfare were supposedly the companies’ job.

You first instinct might be to say Okay la, that sounds fair… until you realise a lot of those “private” companies weren’t exactly private. The government had stakes in them too.

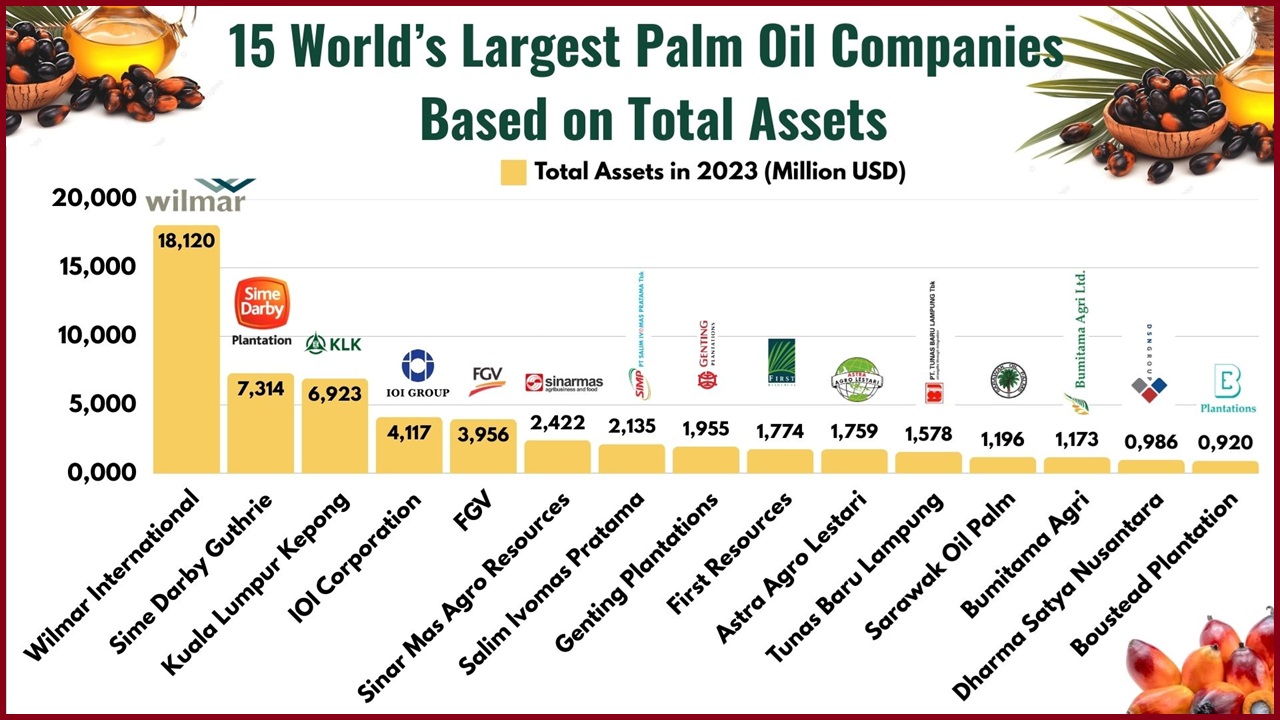

Guthrie and Sime Darby eventually came under Permodalan Nasional Berhad (PNB) after the government’s Dawn Raid in the 1980s. Which means the biggest landlord in the estate was the government itself. So while officials waved off responsibility, they were literally sitting in the boardroom and pocketing their dividends.

It wasn’t until 2001 that estate workers finally got a monthly minimum wage set at RM350. That kind of stability should have been a win after decades of living on unpredictable daily pay. But in reality, Malaysia’s poverty line at the time was RM510 🤦♀️. So again, the workers were shortchanged. By 2007, wages improved to RM650 which still couldn’t cover rent, never mind saving for a house once they got evicted from their quarters.

Which then leads us to the million ringgit question: if the companies (with the government sitting in the front row) couldn’t even pay enough for workers to afford life outside the estate… could they really be expected to give them houses after the job ended?

Pfft.

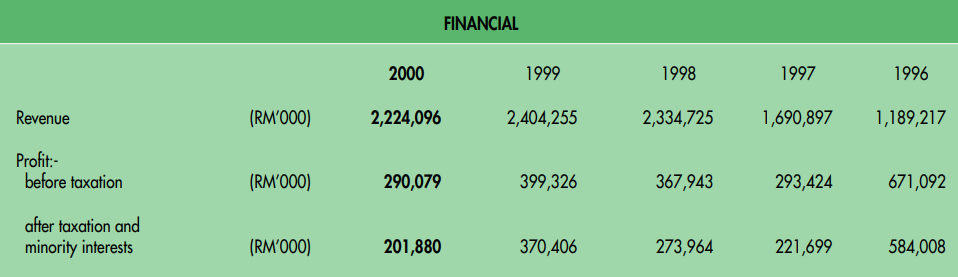

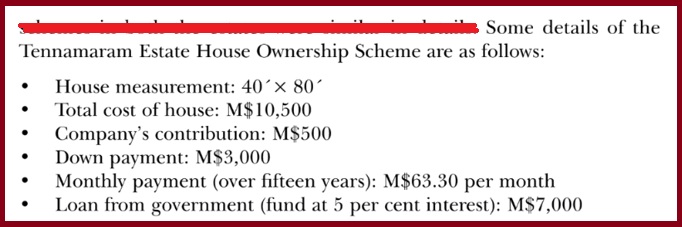

Estate companies were swimming in profits that went nowhere near their workers

Alright, you’ve sat with that nagging thought in your head long enough. Houses cost a lot, that’s a fact. So did estate companies even have the cash to spare for workers’ housing? And if they did, would it have eaten into their profits?

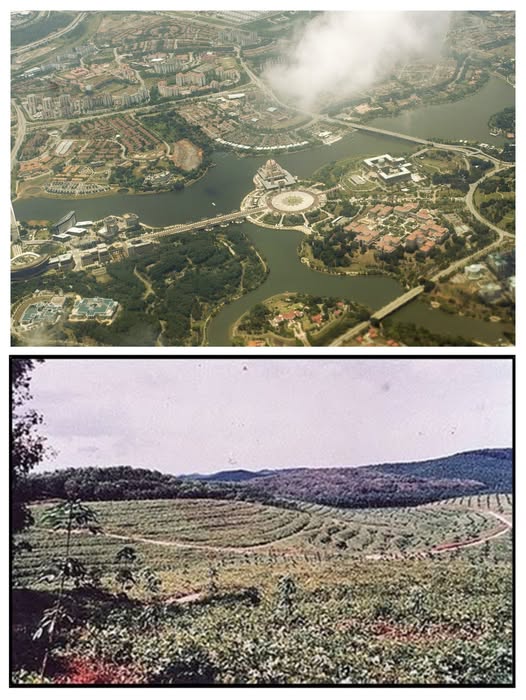

Let’s rewind a bit. When Malaysia started industrialising, plantation land suddenly became the hottest real estate in town. Apart from those sites we mentioned earlier, estates were snapped up to build elite housing projects, golf courses, industrial parks and new townships like Putrajaya, Nilai and Diamond Creeks. In Ulu Selangor alone, the number of estates fell from 21 to 11 in just four years. Johor lost almost all its estates near JB after ten of them were sold off.

Sounds like loss after loss, right? But the companies were actually cashing out big time. The Bukit Rajah estate in Selangor went for RM380 million. KLK sold Tanjung Malim Estate to the government for RM321 million. And ofc with upheavals like that, everyone had to berambus keluar. You’d think, okay lah, maybe termination benefits could cushion the fall for the workers? Some kind of payout to soften the blow?

Well, yes, but it was literally peanuts. Legally, they were only entitled to 20 days’ wages for each year of service. So a worker who had slogged 20 years would walk away with around RM6,000. To put that in perspective, the payout to workers in Tanjung Malim didn’t even reach 1% of the profits KLK made from the sale.

So to all of that we say, what sort of house could the workers buy with RM6,000? And while we’re already talking about the houses, we gotta clarify that these companies were never providing free housing to begin with. They contributed a small amount, yes, but the brunt of the cost was supposed to be shouldered by the workers who were paying back through monthly salary deductions.

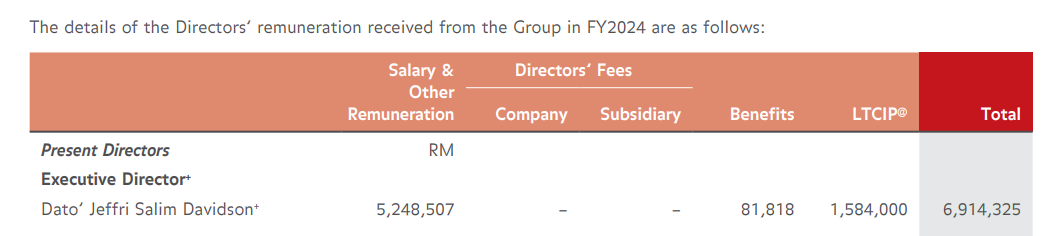

It’s just kinda crazy thinking about the whole thing because on the one hand you have the CEO of these giant companies like Sime Darby earning RM6 million plus a year. Compare that to the average Sime Darby worker’s monthly wage which only very recently increased to RM2,700 from RM1,500 and yeah… the math is as lopsided as it looks. So much so that even the courts sometimes couldn’t tahan the unfairness.

Take this 2003 legal case involving Guthrie. The company’s lawyer argued that retrenched workers had no right to stay in estate quarters once their compensation was paid. The Appeals Court judge then said, Leave and go where? Live on trees? Or cow sheds? Or you’ve got hotels for them? After a couple more back and forth’s, Guthrie’s lawyer said that even if the workers win in the end, they will still have to leave the quarters, to which the judge replied, At the end of the day, if they win they go out loaded; now they go with empty stomachs.

Sike, when even the courts are side-eyeing estate companies, you know something’s off. And this is where the human cost really hits. Because when you boot out workers who’ve spent their whole lives on estates i.e. people whose skills are tied entirely to plantation labour, you’re essentially creating a whole new class of urban hardcore poor.

Most couldn’t pivot to city jobs because they had no transferable skills. Estate workers had worked their entire lives only to be told they were surplus, and then forced into the city with nothing. So now with the government standing back as a silent onlooker and companies doing the bare minimum (heck, sometimes even less 🙄), who else could workers turn to when their very homes were on the line?

NGOs have done more work in the estate workers’ struggle

The first port of call for estate workers was always supposed to be the National Union of Plantation Workers (NUPW). They’re the largest trade union in the country and in fact one of the largest in Asia but honestly, their track record is pretty depressing.

Part of the problem was beyond their control. You see, when estates switched from rubber to oil palm, they suddenly needed far fewer workers. Add in the rise of foreign contract labour i.e. migrant workers (which is almost impossible to unionise) and membership just collapsed. But even on the wage front, NUPW didn’t deliver much.

Although they tried, NUPW couldn’t lift its members much above the poverty line. And a 1989 expose showing union funds going into perks for its leaders didn’t help their credibility. When they tried to push back with a three-day strike to increase their wages in 1990, the government stepped in and basically forced them to settle for crumbs. Safe to say with a string of setbacks, NUPW pretty much faded into the background.

That vacuum left space for others to step in. People’s Service Organisation (PSO) was one of the first, educating workers about their housing rights and pushing estates to improve basic living conditions. But if there’s one group that’s become synonymous with estate struggles, it’s Parti Sosialis Malaysia (PSM).

PSM has been grinding away at this fight for decades. Back in 1991, they launched a nationwide signature campaign demanding that estate workers be brought under rural development policies, instead of being left at the mercy of private companies. That eventually led to Selangor’s 1991 housing policy for displaced workers.

In 1996, PSM kicked off another national campaign, this time for a minimum wage of RM750. At the time, estate workers were still trapped in the daily wage system. It may not have flipped the system overnight, but PSM pretty much laid the groundwork for the Minimum Wage Order in 2013.

More recently, another group called Jawatankuasa Sokongan Masyarakat Ladang (JSML) has been taking the fight directly to the streets. For the longest time, they’ve worked with PSM to push back against evictions and campaign for permanent housing rights. And together, PSM and JSML have now pulled off one of the boldest estate moves in years.

PSM and JSML drafted their own bill and submitted to Parliament

When estate workers and their allies marched to Parliament this August, they had more than just slogans and placards in hand. Led by PSM and JSML, the workers came carrying their own solution.

The march itself was dramatic enough. Police tried to block the group at Parliament’s gates and Arul, the deputy chairman of PSM, even fell and was later arrested. But despite the chaos outside, JSML and PSM leaders still managed to hand over what they came for – a draft law that would guarantee plantation workers permanent housing after retirement.

And the Estate Workers Housing Scheme Act isn’t some half-baked proposal either. JSML had been consulting workers from over 100 estates since 2023. They gathered stories, drafted clauses and basically did the government’s homework for them. Since then, they’ve been knocking on the doors of state governments and ministries all over, trying to push it into law. It’s had a pretty tepid reception so far tho so things are still up in the air.

But if the law ever goes through, here’s the gist of it:

- Estate owners must set aside land and build houses with basic amenities

- Long-serving Malaysian workers can buy the houses at a fixed price of RM48k

- The workers can pay in instalments capped at RM300/month

- A new Estate Housing Board will keep everyone in check

- Any disputes will go through a tribunal

But it’s interesting to note that this also isn’t JSML’s first Parliament field trip. Back in 2019, they showed up with a whole memorandum asking for a public housing scheme. The then–Human Resources Minister, M. Kula Segaran, said he’d look into it and judging by the fact the workers had to show up again, you can guess how that went.

So really the march this time around has been a culmination of all those false promises and dead ends, to the point they decided if the government wouldn’t write the law, they’ll draft it themselves. And on that note…

Why on earth is this law so hard to implement?

As usual, things in Malaysia are never straightforward.

For one, land is a state matter. That means even if Parliament passes a national law forcing estate owners to build houses, the federal government still needs state governments to ikut sama. Every state has its own priorities so let’s say if Selangor is open to it, another state somewhere else might already be eyeing that estate land for lucrative condos. So unless there’s cooperation across all states, the law risks becoming another nice sounding policy that just won’t jadi.

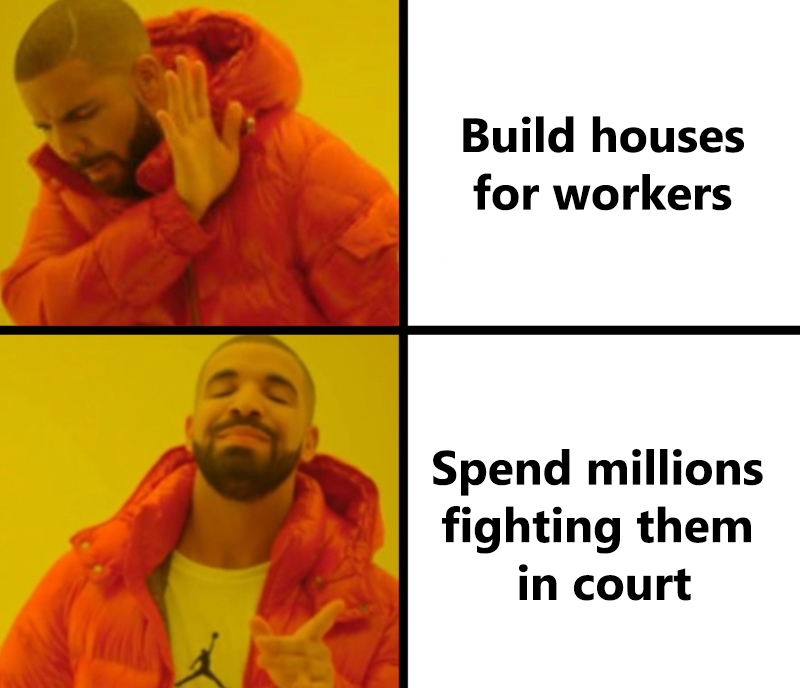

Then there’s the issue of cost. Arul pointed out that estate companies don’t exactly wanna cough up the extra expenses. In fact, you can see it in the way they’ll drag workers through court cases that stretch on for years, just to avoid paying what they owe.

“These plantation companies are powerful. Their argument is ‘other sectors don’t have to build [houses], so why must we build?” – Arul, deputy chairman of PSM

And honestly, when has any business happily agreed to spend more just because the government said so?

The manufacturing sector has long warned that stricter housing standards would eat into employers’ profits. Developers also always complained that the business of affordable housing slashes their margins from a comfy 40% on normal units down to just 10–15%. And even then, they worry that the cheap units end up unsold.

Add to that the usual suspects i.e. red tape, shifting political priorities and the fact estate workers aren’t exactly a powerful voting bloc, and you can see why their housing rights keep getting put off.

It’s about time estate workers stop being sidelined in Malaysia’s welfare system

After independence, different groups were gradually absorbed into state-backed settlement schemes. Malay smallholders had FELDA and FELCRA, where land and housing were allocated in rural areas. Chinese communities were grouped into Kampung Baru Cina through resettlement exercises.

And although they don’t categorically fall under the same vein, estate workers never had that kind of systematic housing program. When plantations downsized, sold land, or switched crops, workers were usually left to fend for themselves. Evictions became a recurring headline and families who had spent their whole lives on the estates suddenly found themselves without a home.

It’s sad af, but it’s a pattern that hasn’t really gone away.

For decades, estate workers have put in the labour that kept plantations running, but when things got tough, they were treated as disposable. Many of their grandparents were literally brought here to clear the land and generations later they’re still struggling to find a place in the country they helped build. Whether the responsibility lies with companies or the government, the point is that someone has to step up.

It’s just kinda sad tho that at this stage, any help feels belated. The workers needed it years ago before their communities were torn apart. That said, there are still pockets of estate workers holding on with nowhere else to go. For them, this law could finally be a first real step towards breaking the cycle. Until then, the least we can do is keep the issue alive by talking about it, pressing our MPs to look into it and making sure it doesn’t get swept under the rug again.