Why do kampung residents in Selangor keep getting kicked out of their homes?

If you grew up in a Malaysian city sometime between the 1980s and the early 2010s, you’ve probably seen your fair share of squatter settlements. These were clusters of wooden and brick houses built close together, cut through by narrow lanes that could barely fit a motorcycle, let alone a car. There’d be electrical wires criss-crossing in every direction and water pipes being pulled from one house to the next.

Most of these settlements sprang up on reserve land, along railway tracks or on empty plots that had been ignored for years. To outsiders, it was easy to write these places off as problem areas. But to the people living there, this was merely how they survived.

And don’t think these places appeared by accident. Many were the result of the big rural-to-urban migration during the New Economic Policy (NEP) years. Cities were booming, factories were opening and people were chasing jobs, hoping to claw their way out of poverty.

The problem was, the supply of low-cost housing back then was nowhere near enough to accommodate everyone flooding in. With wages that barely covered daily expenses, many had little choice but to build their own homes on whatever vacant land they could find.

For years, people lived this way. Children grew up, houses expanded bit by bit and the surrounding neighbourhoods changed. But in the eyes of the law, the land’s status stayed the same. And by that we mean it was still unauthorised for settlement and no one living on it held any sort of legal title.

At the same time, cities kept growing and land that people previously didn’t look twice at suddenly started fetching serious money. Places that were basically invisible a decade ago became hot property overnight. Squatter settlements got caught up in redevelopment plans, all aimed at clearing these communities out. And it was usually around this point that…

Conflicts between the government, developers and residents kaboomed

Some of the areas we call squatter settlements today actually have a history that goes way back. Take Kampung Jalan Papan, for example. It’s been around since 1939 which, if your Math is Mathing, was during the British rule. It started out as a settlement for labourers and urban communities during the Emergency years. So no, this wasn’t some kampung that just popped up overnight. Families have lived here for generations, long before the surrounding neighbourhood turned into a proper modern city.

After independence, the state government allowed residents to remain and issued them Temporary Occupation Licences (TOLs). A TOL is an official document from the state that permits someone to occupy government land for a fixed period, usually a year, for stuff like farming, running a small business or temporary housing. The one thing it doesn’t do is grant that person permanent ownership of the land.

These licences had to be renewed annually and in Kampung Jalan Papan, many families held TOLs from the 1960s through the late 1980s. With these licences, residents could continue living there legally without being accused of encroaching on government land.

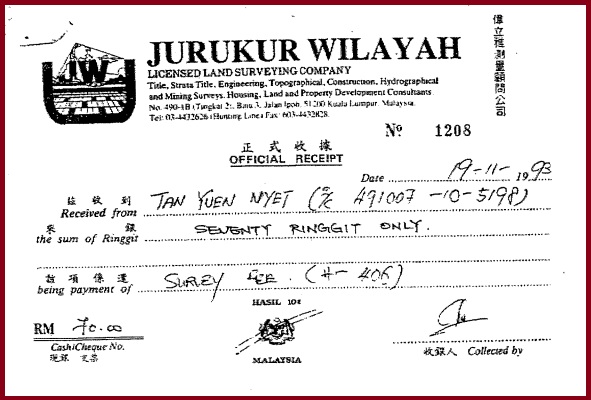

Problems started popping up in the early 1990s, when the state government began surveying land in the village, supposedly to resell it to the residents. People were asked to cooperate and pay RM70 each to the surveyor. After paying though, the residents heard nothing more. Plans for low-cost housing or relocation were kind of up in the air and were never finalised.

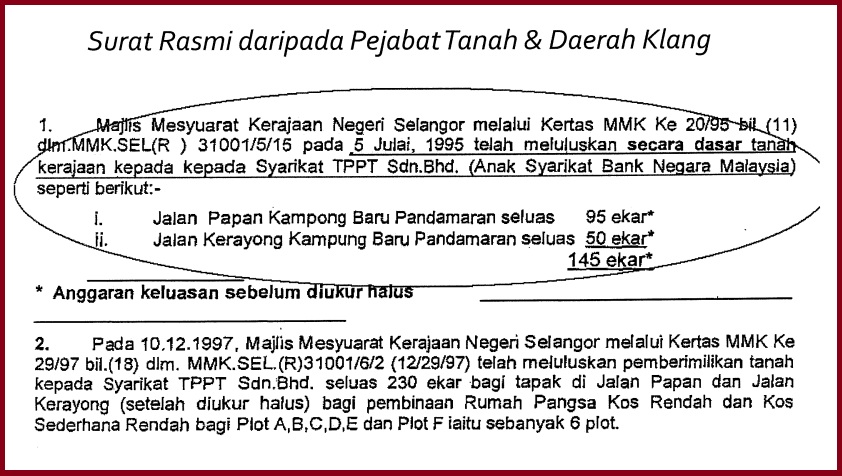

By the mid-1990s, the land in Kampung Jalan Papan was handed over to TPPT Sdn Bhd, a company owned by Bank Negara Malaysia responsible for managing tricky land for development and relocation. Residents were again told about proposed low-cost housing but once more, nothing was finalised. And so life carried on as usual. Or at least it seemed that way.

Tensions started to rise in 2005 when the Klang Land Office issued eviction notices to several hundred families, offering RM7,000 in compensation. Some residents moved, but many refused, arguing that the amount was far from enough for those who had lived there for years. The following year, several houses were demolished and residents took the case to court. Shortly after, the land was sold to a developer, Melati Ehsan Sdn Bhd.

Between 2010 and 2018, negotiations continued with various offers, including low-cost housing and alternative relocation. But these offers were only extended to the original settlers. Meanwhile, the village had grown, families had expanded, and new generations were already living there. So talks kept stalling, and nothing was properly resolved.

From 2020 to 2025, eviction notices were issued again, sparking protests from residents. Demolitions continued regardless. Viral videos showed residents protesting, scuffles with police, the arrest of activists and footage of houses being demolished while still occupied, even though authorities had stated that only empty homes would be affected. And this is where the obvious question comes in…

How did a dispute like this drag on for more than 30 years?

To understand that, we need to zoom out a bit and look at how land ownership works in Malaysia. Under the National Land Code, which has been in force since 1965, land ownership is pretty straightforward on paper. If your name isn’t officially registered, or you don’t hold a land grant issued by the state government, then legally speaking, the land isn’t yours. It doesn’t matter if you’ve lived there for five years or fifty.

Because of that, the law is usually very clear-cut. If someone enters and occupies land without permission and without the landowner’s knowledge, they’re considered a squatter or intruder. In those cases, the landowner can apply for a court order to evict them and there’s no legal obligation to offer compensation.

But Kampung Jalan Papan isn’t your typical land-intrusion case. The residents didn’t sneak in or occupy the land illegally. Their presence was known to the authorities and for years, it was explicitly allowed. They were even issued Temporary Occupation Licences (TOLs) which confirms they weren’t trespassing. That official recognition is also why they had electricity, water, and registered addresses.

In situations like this, residents actually have grounds to challenge eviction orders, because they aren’t occupying the land without the landowner’s knowledge. Courts will usually push both sides towards negotiations i.e. things like compensation or alternative housing. The catch is that these talks almost never run smoothly. Over time, long-term residents end up living alongside people who come later and once that happens, figuring out who qualifies for compensation becomes messy fast.

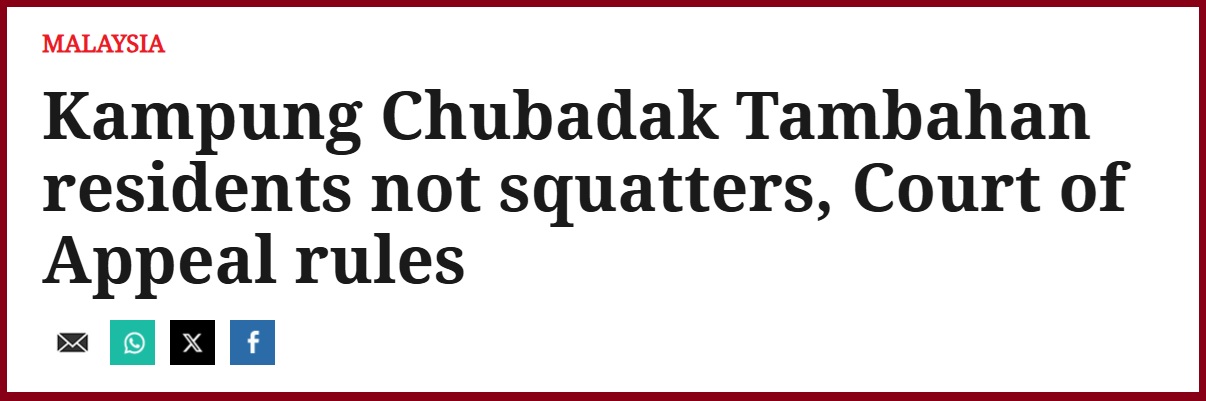

A similar situation unfolded in Kampung Chubadak Tambahan in Kuala Lumpur. In 2000, the Court of Appeal ruled that the residents there were neither squatters nor intruders. They were recognised as lawful occupants who had been living on the land with the state’s permission, which meant any relocation had to come with proper compensation. But that decision didn’t exactly settle things. In 2008, DBKL still listed Kampung Chubadak Tambahan as a squatter area under the Kuala Lumpur City Plan 2020. A few years later, in 2013, clearance works went ahead anyway.

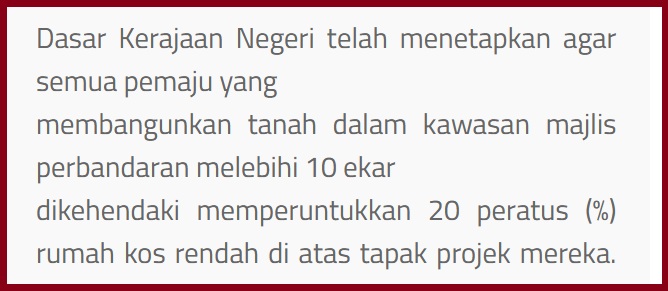

This same pattern pops up elsewhere too. Once a settlement is officially labelled a squatter area and the land is earmarked for development, developers are usually required to provide low-cost housing or alternative accommodation, whether through PPR or other schemes. That’s why developers often end up looking like the bad guys, when in reality, they’re following policies set by the state government.

Then with these rules in place, why do squatter issues keep resurfacing?

At first glance, the issue of squatter settlements and urban settlers might seem like it has an easy fix, but the reality is much more complicated. In the early 2000s, several state governments implemented the Zero Squatters programme, aiming to completely eliminate squatter areas by 2005.

Under this policy, most squatter and urban settler communities were relocated to PPRs or low-cost housing. Compensation was provided either through housing subsidies or cash payments of around RM7,000. In the early stages, the approach seemed to work. Many areas were cleared and new development projects began to take shape.

But as we established earlier, these settlements oftentimes didn’t exist in secret. They were tolerated by authorities for long periods and in some instances even indirectly acknowledged through the provision of utilities and official addresses. That left residents stuck in an awkward grey area where they were not quite squatters, but never legally protected as landowners either.

All this to say, forced eviction should always be the last resort. Recognition of their occupancy or reasonable relocation should come first. And if moving people really can’t be avoided, the process has to be transparent, and that includes early discussions, proper notice and fair compensation. Skip those steps and every eviction just creates new conflict the government will have to handle again and again and again…. and again.