Singapore didn’t invent CNY Yee Sang, this Seremban man did!

- 90.0KShares

- Facebook86.0K

- Twitter369

- LinkedIn173

- Email738

- WhatsApp2.7K

[Ed’s note 1: Some of the contents of this story was sourced from “A Toss Of Yee Sang”, used with permission.]

[Ed’s note 2: This article was originally titled “China didn’t invent CNY Yee Sang, this Seremban man did!” but was changed to reflect claims made in a BBC article that it was Singaporean. More on that drama here.]

Yee Sang, otherwise known as Lo Hei (捞起) is one of the most anticipated traditions of Chinese New Year – without a doubt. If you’re not sure what it is (seriously?!), Yee Sang is basically a Chinese salad dish with raw fish/jelly fish and a special sauce, while Lo Hei is when you toss the salad as high as possible using chopsticks while shouting out good stuff you hope would happen in the coming year.

Yee Sang is crazy popular in Malaysia and Singapore, but most Chinese in the rest of the world have absolutely no idea why we’re playing with our food like this! So if most Chinese don’t know about Lo Hei Yee Sang, where did this Chinese New Year tradition come from?

It all began with one man from Seremban who needed to make some extra income. But before we tell you his story, let’s go back in time to China and see how this dish really came about.

A long, long time ago, in a land far, far away…

Raw fish cuisine, also known as kuai (脍), was very popular in China thousands of years ago. The earliest records of China (written about 3,000 years ago) show that kuai cuisine was very popular among the social elite and was a standard dish at royal banquets. Kuai was often mentioned in ancient Chinese texts like the Classic of Poetry (诗经, Shi Jing), the Analects of Confucius (论语, Lun Yu), and the Romance of the Three Kingdoms (三国演义, Sanguo Yanyi).

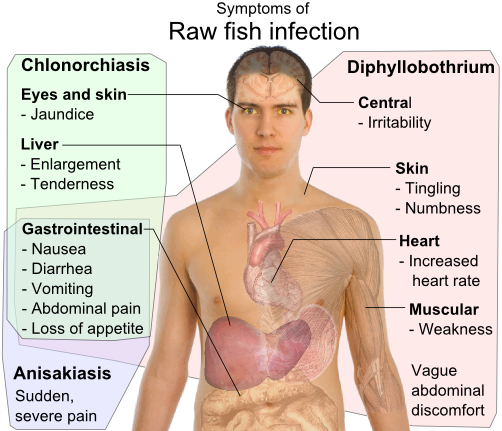

Although it had been popular for thousands of years, kuai cuisine eventually died out as Chinese cooking became more and more awesome over time. Also, as Chinese medicine developed, physicians discovered health hazards of eating raw food, like parasites living in the flesh of fish. Naturally, the Chinese people began to feel more and more geli about eating raw fish.

But raw fish cuisine has not completely died out in China. Yusheng (鱼生), a traditional dish with raw fish, still survives in the Southern region of China. By its name, you should already kinda guess that this is the ancestor of the CNY Yee Sang we enjoy today! But it’s very different from the Lo Hei Yee Sang we know and love.

For starters, Yusheng in China is NOT a CNY specialty (some of you are going whut?).

There’s absolutely no Lo Hei (gasp!).

The raw fish is the star ingredient while the vegetables and sauces are optional side ingredients (no!).

And each diner chooses what they want to go with the raw fish and mixes them on their own plates (apa ini?!).

Each region has its own Yusheng variation of ingredients, flavourings and styles of preparation, all of which are very different from Lo Hei Yee Sang as well. And although it is available throughout the year, yusheng is still not a commonly eaten dish because Chinese people geli mah, eating raw fish.

[Ed’s note: If you want a taste of authentic China-style yusheng, there are a couple of places you could try to find it in Malaysia (here and here). Can’t say when they serve it or even if it’s still available though.)

So… how on earth did Yusheng end up in Malaysia as a CNY tradition?

Yusheng culture was brought over to Malaya by Cantonese and Hokkien immigrants who arrived from the late 1800s onwards. But it was also not popular here. If it wasn’t for the ingenuity of one Chinese immigrant, Yusheng may have remained a little-known dish plodding slowly towards extinction. But sometime in the 1940s, a man named Loke Ching Fatt introduced his own version that would eventually become the Lo Hei Yee Sang Malaysians know and love.

Loke Ching Fatt came to Malaya and settled down in Seremban sometime in the 1920s. The hardworking young man set up a catering business called Loke Ching Kee, cooking up Chinese banquets for weddings and other special occasions. With his hard work and dedication, Loke’s business flourished and he was often called to cater at smaller towns and villages all over Negeri Sembilan.

But the good times came to an abrupt halt during the Japanese Occupation. Loke, who was married and had 6 young children by then, fell on hard times. Not many people could afford to throw banquets during the turbulent War years, and his business was hit hard. Somehow the young family survived.

After the war, Loke’s catering business was still slow to pick up. The Chinese community was slowly recovering from the harsh Japanese occupation, and he knew that the quietest period of the business was coming – Chinese New Year. At that time, people would lavish what they could for the Chinese New Year and cut back on spending in the months following. Loke had to think of ideas to drum up business.

He remembered that the Cantonese had a tradition of eating Yusheng on Renri, the seventh day of Chinese New Year, and decided to revive the tradition. But instead of preparing Yusheng the traditional way, Loke would create a much more elaborate Yee Sang recipe.

An unexpected CNY food tradition was created

Loke’s complex Yee Sang recipe had about 30 ingredients (many of which have been dropped or changed in today’s modern versions). His recipe was a multi-coloured combination of various Cantonese, Teochew and Hokkien Yusheng traditions, with a big dash of his own creativity. Of course, no legendary dish is complete without a secret ingredient. In Loke’s Yee Sang, it was his signature sweet and tangy sauce.

Originally, Loke called his recipe Sup Kum Yee Sang (十感鱼生, or the “Tenth Sense Yee Sang”). According to Buddhist beliefs, the Tenth Sense is the ability to sense infinite dimensions. This name described Loke’s Yee Sang creation very well as it had an incredibly complex combination of colours, aromas, flavours and textures.

Loke also decided to serve it banquet-style, hoping that a joyous atmosphere would attract more customers. And it worked! Loke had created a killer recipe that customers soon fell in love with. They could not get enough of the taste of Loke’s Yee Sang and they loved the merriment of the banquets. Word began to spread and Loke’s Yee Sang grew more and more famous.

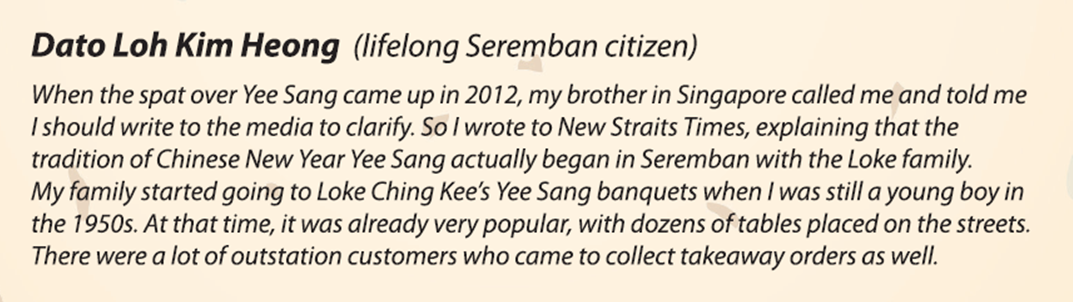

In just a few years, what started out as a small banquet with a few tables grew into an annual sold-out event lasting most of the Chinese New Year season, with dozens of tables served every evening and a long line of customers waiting to tapau. Loyal Yee Sang fans would come all the way from Melaka, the Klang Valley and even Sabah, just to get the once-a-year taste of the famous Loke Ching Kee Yee Sang.

By the 1960s and 70s, it had become an entrenched tradition to have Yee Sang for Chinese New Year in Seremban. Customers faithfully came for the Yee Sang banquets every year, bringing their second and even third generations with them. The business would have continued to grow had it not been for the fact that Loke could no longer cope with the volume of demand.

By the 1970s, Loke had passed on the responsibility of hosting the Yee Sang banquets to his second son, Loke Chee Chow. The elder Loke was content to take a back seat, quietly manning the cash register until he passed away in 1978. The Loke family’s Yee Sang banquets continued until Chee Chow himself retired in the mid-1990s. It was the end of an era that had lasted for about 50 years.

But the CNY Yee Sang tradition Loke started lives on. By the 60s, many other restaurants were regularly serving CNY Yee Sang. The popularity of Yee Sang continued to spread throughout Peninsular Malaysia and eventually to the other Chinese communities in South East Asia. Today, it would be unthinkable not to have at least one Lo Hei Yee Sang for Chinese New Year!

So Loke created CNY Yee Sang, but ‘Lo Hei’ happened by… chance?

According to Loke’s eldest daughter, Loke Foong Ying, nobody invented the Lo Hei! It just happened naturally. But even though Loke did not invent the Lo Hei, he was still indirectly responsible for it. Here’s how it happened.

Loke was a perfectionist and he expected the taste, texture and presentation of every Yee Sang dish to be exactly the way he wanted. So he strictly controlled how it was prepared to ensure his signature taste was intact. Which meant no free-styling, like how people ate Yusheng in China.

When the plates of Yee Sang arrived at customers’ tables, the servers added the ingredients in a specific sequence to ensure that the best texture was achieved. Then the ingredients had to be thoroughly tossed. Tired of waiting for the servers to mix it up, hungry diners would go at it themselves with their chopsticks. With everyone tossing together, they could mix the dish up faster and eat sooner! This quickly became the normal way of eating Yee Sang.

On one occasion, a group of high-spirited youngsters got the idea to call out auspicious wishes while tossing the dish (they may have been high on other “spirits” too, who knows). Then they thought it would be fun to see how high they could toss it as well. The idea caught on and that’s how the Lo Hei tradition started!

All of this evolved naturally because Loke Ching Fatt would not allow his customers to eat his Yee Sang any way they liked.

But wait, Singapore ALSO said they invented CNY Yee Sang!

Typical of Malaysia & Singapore’s love-hate-relationship, there just had to be some kind of controversy – even over the origins of our food. Previously, there were huge arguments about Bak Kut Teh, Chili Crab and Chicken Rice. It’s no surprise that something as culturally significant as CNY Yee Sang would spark a war of words.

In 2012, Singaporean celebrity foodie K.F. Seetoh shared a Facebook post listing six Singaporean things that should be listed on UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage list. One of them was Chinese New Year Yee Sang. This suggestion quickly turned into a cross-border firestorm. Malaysians argued that Yee Sang began in Seremban in the 1940s while Singaporeans insisted that the dish was created in the 1960s by the “4 Heavenly Kings”, a group of famous chefs in Singapore. The spat was so fierce that it even made CNN’s list of “7 of the world’s fiercest food feuds”.

Eventually, two of the surviving heavenly kings, Hooi Kok Wai and Sin Leong, explained in an interview that they never claimed to have “invented” Yee Sang but merely developed their own unique Yee Sang recipe in the 1960s. They urged the public not to bring up the controversy anymore and remember that Yee Sang is meant to bring people together and not divide them.

Over in Malaysia, Loke Chee Chow, Loke Ching Fatt’s heir, also urged citizens from both countries to set aside their differences and stop arguing about Yee Sang’s origins. Loke diplomatically acknowledged that is was difficult to say for sure who first served Yee Sang, given its long history stretching back to ancient China. Thankfully, the controversy died down after a few weeks and everybody went back to enjoying this delicious dish that uniquely belongs to this part of the world.

Despite the controversy, it’s good to remember that the CNY Lo Hei Yee Sang tradition that we enjoy today can be reliably traced back to Loke Ching Fatt and Seremban. It’s important for us to remember and understand our heritage in order to appreciate it and preserve it for the future generations.

No one could have foreseen that one simple man’s attempt to earn some much-needed extra income for his family would become a phenomenon that would outlive him and last for generations. It was Loke’s dedication to his craft that has made Yee Sang the rich tradition it is today. In fact, the popularity of Lo Hei Yee Sang even seems to have far overtaken its Yusheng ancestor in China. Today, Yee Sang continues to cross national borders and cultural barriers, gaining popularity among non-Chinese people.

But as both the Loke family in Malaysia and the Heavenly Kings in Singapore pointed out, what is most important about Yee Sang is not its origin but its significance. This unique expression of togetherness and blessing is meant to unite people. And Yee Sang has been doing that for years, bringing people of various creeds and colours together at the dining table. After all, CNY Yee Sang is typically had over dinner with friends and family, especially at Tuan Yuan Fan (团圆饭) which literally means, “to gather all together and form a perfect unbroken circle for a meal”, signifying that friends and families should work towards creating a perfect unity (at least for once a year la!)

So this Chinese New Year as you enjoy tossing your Lo Hei Yee Sang, whether you’re Singaporean or Malaysian, white, black, yellow or brown, let’s not break that perfect circle. When you shout out the New Year Lo Hei blessings, shout one out for our cousins across the border too, can?

Can lah!

*If you want to know more about the fascinating history of Yee Sang (and pick up Loke Ching Fatt’s original Sup Kum Yee Sang recipe), go to Amazon to get a copy of “A Toss Of Yee Sang”, the commemorative book published by Loke Ching Fatt’s grandchildren.

PS: If you’d like more stories like this, please subscribe to our HARI INI DALAM SEJARAH Facebook group 🙂

- 90.0KShares

- Facebook86.0K

- Twitter369

- LinkedIn173

- Email738

- WhatsApp2.7K