Do other countries have Arts and Science streams in their schools, like Malaysia?

- 1.1KShares

- Facebook1.0K

- Twitter18

- LinkedIn23

- Email22

- WhatsApp57

[This article was originally published in February 2019, and have since been updated to reflect current events.]

So here’s a quick question for you: back in sekolah menengah, did you take the Arts stream or the Science stream? Well, whichever one it was, hold on to that memory tight to tell your grandkids, because by the time they get into school, streams may be no more.

The Education Minister Maszlee Malik had recently revealed plans to sorta kinda merge the two streams together, creating streamless schools where students learn not only the sciences, but Art subjects as well. This plan had been suggested to him by the National Education Policy review committee, which his ministry set up some time ago to… come up with ‘new and innovative ideas for the education system‘.

“We are not going to put our students into Science and Arts (streams) anymore. In a new curriculum we will implement, we will not only emphasise Science, but also Arts (and culture) because knowledge is one; it cannot be compartmentalised and should be integrated instead,” – Maszlee Malik, to the Star.

Now before we get any further, let us stress that as of the time of writing, it’s just a mention of a plan, with nothing concrete announced yet.

[UPDATE 17 OCT 2019: Education Minister Maszlee Malik had reportedly revealed to the Malaysian diaspora in Germany that it will be implemented starting next year (2020).

“So starting next year, Science and Arts students can choose and combine the subjects they like. I’m pushing for it. Many parents make their children pursue their own dreams, which is not right,” – Maszlee Malik, as reported by Malay Mail.

END OF UPDATE]

[UPDATE 21 OCT 2019: Maszlee had reportedly said that his speech in Germany wasn’t exactly a policy announcement, but rather… something else.

“The ministry has not made any policy announcements (regarding the abolition). What happened was my speech at a town hall session in Germany. The report sounded as though the abolition was a policy announcement, but in fact, it is not yet.

“What I said was in the future, we want to ensure that students are not stuck with the streams, for example, a science student cannot take-up literature while there are some art students want to take science subjects. But the report was portrayed as though it was a policy statement,” – Maszlee Malik, as reported by Malay Mail.

As for when exactly it will happen, Maszlee had said that it will be announced when the time comes. Oh well. END OF UPDATE]

Still, it was mentioned that STEM (short for Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) education will be updated to include two new elements, Arts and Reading (making it STREAM). And while it’s still in the planning stages, you might be wondering…

Do they have streaming in other countries as well?

In case you’re not familiar with the current streaming system in Malaysia, basically starting in Form 4 (16 years of age) students can choose either the academic stream, vocational/technical stream, or the religious stream. For this article, we’ll only be looking at the first one. If they choose the academic stream, they can further choose between the Science stream or the Arts stream, whose difference is in the subjects taken. Science stream students generally take up subjects like Add Maths, Physics, Chemistry, Biology, and English for Science and Technology (EST), while Arts students can take practically everything else, up to and including Geography, Music, Visual Arts, Accounting, and Economy.

[Note: The orange numbers next to the countries’ names represent their ranking on the top 40 best education systems in the world, according to Pearson. The ranking considers all levels of education, from primary to higher. If a country is not listed, the number will be zero.]

As far as we can tell, some countries have a similar kind of arrangement to ours. At 16 years old (Grade 10) in India [], students can choose either the Arts, Science, or Commerce stream. Mexico [39] also has some form of streaming in their preparatoria at about ages 15 – 17, but only for the final year, when they can specialize into either a Physical Science or a Social Science stream. In Japan [2], they can pick either a general, specialized/vocational or integrated course for upper secondary (starting at 15). Probably more countries have these divisions, but we can’t find specific mentions of them, so… yeah.

In many other countries we’ve looked at, there are some form of specialization, but they are more towards academic ability rather than subjects. In Canada [7], for example, students in Grades 9 and 10 (ages 14 and 15) get to choose whether they want to learn in the academic stream or the applied stream. The subjects offered for the streams are the same, but the approach to learning and the expected results are different.

Academic courses are more theoretical, and are geared towards getting the students into tertiary education. Applied courses, on the other hand, are more practical (and some say easier), and are geared towards getting the students a job after high school.

Closer to home, Singapore’s [3] streaming system starts as early as our Form 1 (age 13). Based on their national Primary School Leaving Examinations (PSLE) results, students are sorted into four different houses streams: Express, Normal (Academic), Normal (Technical), and Integrated Programme. It’s a bit complicated, but Normal streams are four year courses with slightly different subjects depending on whether it’s Academic or Technical, and they go through N-level exams, with a possibility of an additional year ending with O-level exams.

For reference, SPM is an O-level exam, and STPM is a bit below A-levels. N-level comes before O. The Express stream is also a four year course, but it ends with an O-level at the end of four years, so it’s one year faster than Normal stream. And the Integrated Program bypasses O-levels and goes straight to either A-levels or an International Baccalaureate Diploma after six years of school.

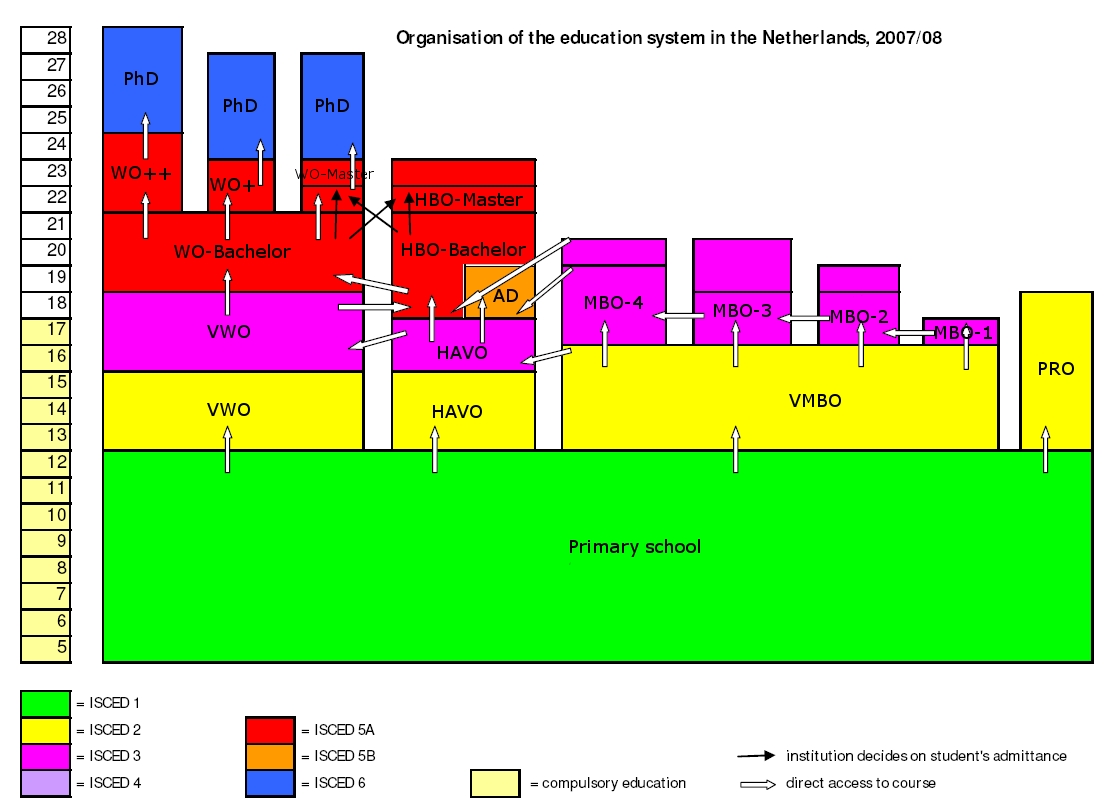

Singapore’s streaming model kinda looks like that of the Netherlands [8], but we’re not touching that with a ten-foot pole. If you want to, you can read about it here.

Anyways, you can see that while different countries have different policies regarding secondary education, overall the themes are pretty much the same: providing education at a level that’s suitable for each student’s interests and capabilities. Heck, even the STEM going to STREAM is not an originally Malaysian idea. While we can’t find explicit instances of a country merging Arts and Science into one stream, it should be noted that…

A majority of Malaysian students won’t (or can’t) take Science

If you were to read the comments on the recent news, you’ll find that some people who disagree with the idea of unifying the Science and Arts stream do so because they’re concerned that Arts-oriented students won’t be able to keep up with Science-based subjects. And the notion is not baseless. To get into the Science stream, students need to get pretty good grades in PMR for Maths and Science, while there’s no prerequisite for getting into the Arts stream. This lends to the impression that the Science stream is for students who are smart, and the Arts stream for students who don’t make the cut.

That notion may not be true, because there are students who qualify for the Science stream but chose Arts instead (as many as 15% of the candidates in 2014, an increase from previous years). However, the preconception remained, with some feeling that it’s easier to pass the SPM if you take the Arts stream.

“That is the perception at the moment. Science subjects have to be taught in an interesting way in schools. There is too much theory at the moment. Students find it hard to relate to the subject,” – Prof Teo Kok Seong of Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, to FMT.

This is perhaps why even though the government had targeted for a 60:40 ratio of Science students to Arts students, the proportion of those taking Science had historically remained low, with the ratio being 21:79 in 2015. As of last year, the ratio had improved by a negligible amount, being 22:78. In some places, the ratio may even be lower, with only 4.5% of Sabahan students picking up Science compared to more than 90% picking Arts, according to a 2016 report. This is very different for other countries like South Korea [1], Finland [5] and India, where the percentage of Science students are 70%, 50% and 73% respectively.

Malaysia desperately needs more science students who can go into STEM after finishing high school, because as of 2016 we have less than 3% of our workforce working in STEM, which is a far cry from the 30% of global economic giants like Japan, Singapore, the US and Germany. Based on a 2015 Akademi Sains Malaysia report, Malaysia needs at least 270,000 science students taking the SPM each year, but we only have about 90,000. At one point, an academic even suggested making it mandatory for high scorers in PT3 to take the Science stream, so we know that something’s up.

Upon graduation from high school, Science students have the option to move to an Arts-related field (some opted for the Arts in Form 6 because it’s ‘easier’), but Arts student can’t pick up Science-related degrees, simply because they “have not done SPM pure science“. The new plan to do away with streams may open up more doors to a huge portion of future students, potentially increasing the number of people involved in STEM. Besides that, there are a host of other possible advantages and drawbacks, which we won’t really explore now based on the announcement of the plan alone. But one thing we can notice is that…

Our education system is moving… but where to?

Earlier this year, some schools have started removing class streaming, or the practice of putting more gifted students in the top class, and less gifted ones in the bottom class. This move was said to be an attempt to reduce the achievement gap between students. While the move received mixed reactions from parents, the National Union of Teaching Profession (NUTP) had welcomed the move, saying that streaming classes based on academic achievement did not promote unity and integration in schools.

“At the primary school level, much of the syllabus involves group work and if the pupils mix around, then moral values can be fostered,” – Kamarozaman Abd Razak, NUTP president, as reported by Today Online.

In a way, the move changed the focus of primary education from academic achievement to a more wholesome approach. The announced STREAM plan, which seem to be in the same vein, if carried out will push back the need for students to decide on a specialization a bit later, allowing them more time to think about what they want to do in life. While there are pros and cons to consider, these new initiatives seem to signal movement away from our traditional methods of education, but whether it’s for better or for worse, we will have to wait and see.

As of the time of writing, nothing concrete about STREAM had been announced yet, but we’ll keep you updated on that. In the mean time, Harry Tan, the sec-gen of NUTP, had suggested for the government to do a pilot study first on its implementation to reduce the pushback from stakeholders on the plan.

“…for this one, we believe that the administrators must study the pilot project carefully and then make sure that all the stakeholders are involved and they can come up with a finding of ways to address the problems that they find along the way, and then before that they will make sure that everything is all nicely practiced before they carry it out throughout the country,” – Harry Tan, to BFM.

Until then, what do you think of this new streamless approach?

If you picked the third option, you’re not exactly wrong. A lot of comments on the news report and the BFM podcast highlighted other dire problems that face our education system. We once wrote about how there was a controversy regarding Malaysia’s 2015 PISA scores (Programme for International Student Assessment), when good students were allegedly cherry-picked for the test but the scores are still below the global average (albeit improved from 2012). And of course, there’s that former principal who went recently lectured Maszlee on the shortcomings of our education policies. Something needs to be done, and as Liong Kam Chong, an avid education commenter had put it,

“Perhaps it is time we re-focus and re-emphasise on pedagogical content knowledge. Teachers must know their subjects. They must acquaint themselves with the latest teaching methods and technologies to deliver better lessons. They must impart full understanding of the topics taught to their students. If students do not understand a topic, no thinking skills can help them solve a Mathematics or Science problem that demands basic knowledge and understanding of the components involved.” – Liong Kam Chong, to NST.

- 1.1KShares

- Facebook1.0K

- Twitter18

- LinkedIn23

- Email22

- WhatsApp57