Can Malaysia REALLY afford to hire an extra 250,000 civil servants? We calculate.

- 592Shares

- Facebook572

- Twitter4

- LinkedIn4

- Email5

- WhatsApp7

Since today’s topic is quite heavy, let’s start with a riddle. How many civil servants can the Malaysian gomen hire, if the Malaysian gomen can hire civil servants? The answer to that would be 1.7 million, according to several reports.

It’s a lame riddle, but it’s a conversation starter. It’s no secret that we have too many civil servants – 1 for every 19 people – and it’s costing the government a lot of money to keep them.

People have been calling for the government to trim the civil service for years, so when a memorandum got sent to the government recently asking them to take in another 250,000 civil servants, it was quite interesting. The memorandum was drawn up by a coalition of government contract workers called the JPKK (Jaringan Pekerja Kontrak Kerajaan), and it was supported by several opposition MPs.

Among other things, it highlighted the woes facing contract workers like cleaners and guards working in government schools and hospitals, and it urged the government to absorb them into the civil service as a solution. While it doesn’t explicitly say how many workers should be absorbed, it does mention that there are roughly 250,000 contract workers facing the predicament right now.

But as we’ve mentioned earlier, the civil service is already very bloated, and it’s already costing the government a lot of money. Can the government afford another 250,000? Will they implode if they take them in? Isn’t this request a bit too unreasonable? Actually, for that last one, it’s interesting to note that…

These cleaners and guards were originally government servants to begin with

These cleaners and guards are often referred to as ‘government contract workers‘, but to avoid confusion, we should note that there are generally two different-ish kinds of contract workers in the government:

- the ‘professional’ kind, or

- the ‘lesser’ kind.

Note that we made up these nicknames to illustrate a point. Don’t go around calling people ‘lesser’ k? Unless they’re tiny, then can.

Anyways, the difference that’s relevant to this article is that ‘professional’ contractors are hired to fill in jobs that already exist in the government’s pay grade system, and the ‘lesser’ ones fill all the other job titles that either don’t exist, or were made obsolete from the system. For example, if the government wanted to do a one-time research project, they might contract a Research Officer (pay grade Q41), a post that exists in the system. That’s a professional contractor.

If they want someone to mop up the blood in emergency rooms, they might hire a cleaner, but there’s no job title for that in the government’s list. So they’ll open a tender for contractors to supply cleaning services. The cleaners are then indirectly hired by the government, through the contractors. These are the ‘lesser’ government contract workers this article is about. The money to pay these two kinds of contractors are also recorded in separate government accounts.

While today there’s no post like cleaners and gardeners in the government system, there used to be back in the early 90s. The government then made such jobs obsolete in the government system to cut costs during the National Privatisation Policy time, and these were outsourced to private contractors. Interestingly, there is a job title for security guards in the government’s systems, but for some reason government schools outsource these jobs.

So now that you have a rough concept of how things work, you’ll notice that the ‘professional’ kind of contractors are kind of directly under the government, while the ‘lesser’ kind are under whichever private contractor that won the government tender. Although it could be due to other factors, some had alleged that a number of these contractors are essentially a product of nepotism and cronyism, and so some workers under them had to go through things like

- low pay, even below minimum wage in some cases

- no yearly raises, with some getting paid the same amount as a freshie even after 20 years of service

- no job stability, with terminations without notice and dubious hiring practices

- being victimized by cost cutting measures, like not given adequate PPE or subpar equipment

- getting warning letters for asking about things like annual leaves or salary

- …and basically just being abused as workers.

These kinds of things had been happening to them for quite some time already, but the pandemic made things worse for them. For hospital cleaners, particularly, they’re not even considered frontliners by the government despite them literally cleaning hospitals, and some of them were allegedly not even allowed time off to quarantine despite being tested for Covid-19 because of concerns over staff shortage.

Due to these sucky things, the memorandum by JPKK essentially demanded for the government to make their jobs more secure by absorbing these workers as civil servants, and cutting out the middlemen.

So maybe these workers asking for a bit more stability isn’t that unreasonable, but can the government afford taking these people in as civil servants though? How much of a difference will 250,000 extra gomen workers have on the national budget? That’s what we’re going to find out today, so take out your calculators…

…because it’s time to crunch some numbers! For the purpose of of simplification, we’ll be considering all of them to be either guards or cleaners. So…

How much will the government need to pay them for the first year?

Short answer: At least RM3.639 billion.

Assuming that absorbed contract workers will be placed in the lowest pay grade possible, the strategy here is to find out the possible amount of pay and just multiply by 250,000. While we did mention earlier that ‘lesser’ contract jobs don’t have a pay grade, it seems the government did have a pay grade for security guards, the lowest one being KP11. Cleaners don’t have a grade, but according to the list of obsolete jobs, many were adapted into either ‘Public Assistants’ (H11) or ‘Operation Assistants’ (N11), so they might be paid the same as these titles.

The minimum starting pays are:

- KP11: RM1,205/month

- H11: RM1,218.00/month

- N11: RM1,216/month

- Average: RM1,213/month

We’re using the average since we don’t know the exact proportions of cleaners to guards. Anyway, multiply RM1,213 by 12 months for 250,000 people will give us an initial expense of RM3.639 billion for the first year.

Note that civil servants often have other allowances and benefits which can be quite substantial, but we won’t be including that in our main calculations since we don’t really know whether they’ll get those. To keep things real simple, we won’t go into stuff like medical benefits and whatnot, but if you’re curious, the KP11 job seems to be entitled to RM695 in allowances like housing, civil service allowance, and living aid every month. That’s about half of their basic, so adding them in the calculations will have a substantial impact: the new total would now be RM5.724 billion.

Getting back to our main calculations, RM3.639 billion is just for the first year. We assume the government won’t fire them all the very next year, and as government servants, they’re entitled to yearly increments, so…

How much will the government need to pay them over the next 25 years?

Short answer: At least RM172.77 billion.

Government servants receive a fixed yearly increment until they reach a maximum amount for their pay grade, after which they can either get promoted to a higher grade or continue to be given increments at a rate of 3% of their maximum amount. All three of the pay grades we mentioned earlier receive an increment of RM80 a year, until they reach their maximum of RM2953.67 (averaged) when they’re 52, after which their increment will be RM88.61 a year.

We know that because we did the math in a separate Excel sheet (can pm tepi). In the interest of simplicity, we’ll standardize all 250,000 workers to start at 30 years of age and retire at 55, with a final pay of about RM3,238/month. This gives them 25 years of service. Without allowances, the government will have to pay them…

- RM6.039 billion/year after 10 years

- RM7.239 billion/year after 15 years

- RM8.439 billion/year after 20 years

- RM9.716 billion/year after 25 years

Adding the total amount throughout the 25 years, including the first year, will bring the total bill to RM172.77 billion. Or RM215.18 billion with allowances. But it’s not the end of the road. Civil servants can still get paid after they retire, so…

How much will the government need to pay them after they retire?

Short answer: At least RM136.7 billion.

So once you’ve worked long enough for the government, you can opt for a pension scheme instead of KWSP. Basically, you get three things if you opt for the pension scheme:

- Monthly pension payments

- A one-time gratuity payment

- Money for all the annual leaves you didn’t take

The amount you can get is based off of several factors like how long you’ve been working, what your last pay was, and some fractions, which we won’t mess with. You can check out the formulae to calculate those through this link, but why bother when the government have already built a calculator specifically for this?

It’s a simple matter to key everything about our hypothetical workers into the calculator, and assuming that they all used up their annual leaves, each of them can potentially get

- A one off gratuity payment of RM73,116.59

- Monthly pensions of RM1,624.81

But wait, there’s more! Starting 2016, it seems that even pensions have an increment of 2% every year. Unlike the pay increment though, the 2% pension increment is cumulative. Pensions are in effect until the pensioner dies (we won’t get into pensions being passed to wives and children for simplicity), and the average life expectancy for Malaysia is now about 75 years, meaning they can enjoy 2o years of pensions on average.

So putting everything into Excel will give us a rough total of RM473,743.31 in pensions for one person for 20 years. Add the pensions and gratuities for 250,000 people, and we get RM136.7 billion in total, post employment.

Just for fun, the minimum total amount we calculated to take in 250,000 low-level civil servants from start to finish is a whopping RM309.5 billion, which is around the size of our yearly budgets. This amount doesn’t really matter, since it’s spread out over like 45 years. But still, for the other numbers, you might be wondering…

Uh… so can the government support those numbers or not?

Short answer: Most probably yes…

…but to be fair the government can do anything if it puts its mind to it. Malaysia Boleh wan!

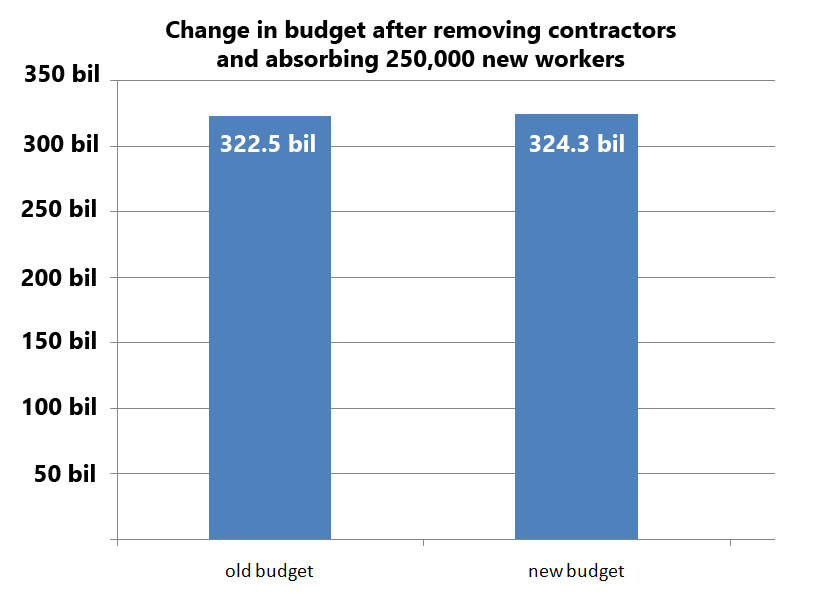

But seriously, after taking out what we’ll be paying these contractors in the 2021 Budget and adding in the new numbers for the first year, the difference is about RM1.737 billion more. That’s an increase of 0.54% from the original budget.

So it’s a half percent’s difference, but we can’t say if that’s little or big when it comes to national finances: our analysis isn’t BNM-level accurate, and we’re only taking into account the absolute minimum amount. Still, since we’ve already dived into 2021’s Budget, for perspective here are some random allocations. That RM1.737 billion is roughly

- 42 times what the government is planning on giving FINAS (RM41.09 million)

- 4 times the total budget for the Ministry of National Unity (RM423.29 million)

- 0.86 times what the government planned to spend on the Pan Borneo Highway this year (RM2 billion)

- 0.67 times what the government will be spending on ‘increasing KTMB’s capabilities’ (RM2.619 billion)

In addition, if we averaged out the changes in the government’s budget allocation for the past ten years, we can say that it increased by around RM10.5 billion each year on average, roughly 5 times the bill for the 250,000 new workers. So in the scheme of the budget, a 0.54% increase probably won’t make the government implode or go bankrupt, especially if they don’t take in all 250,000 at once.

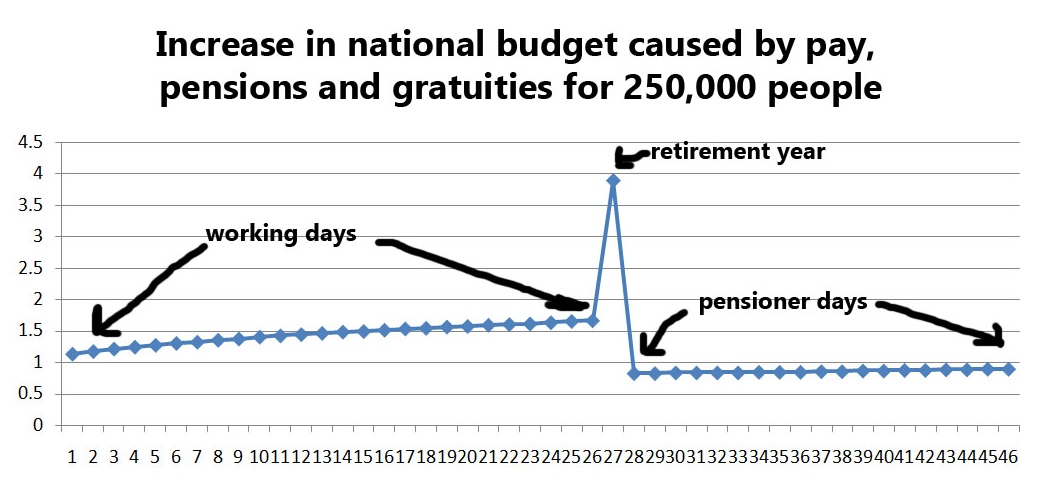

But what about long-term, though? Extrapolating the future budget using that RM10.5 billion increase/year from earlier, we stacked up how much these workers’ pay, pensions and gratuities will increase the budget for the next 46 years, in percentage difference.

So apart from the year where they all retire and get a lump gratuity payment, generally the money that goes to these workers stay under 2% of the extrapolated national budgets for each year. So the strain from adding 250,000 lower grade workers to the civil service won’t exactly be negligible, but it’s perhaps not as heavy as one might think. Overall, it seems pretty doable, however we should also remember that…

We’re already spending too much on civil servants to start with

According to JPKK’s memorandum (which we contacted them to get), by cutting out the middlemen in the contract system and reducing litigation and admin costs from handling the problems caused by it, the government can actually save money by absorbing these workers into the civil service. And as we’ve explored over the past 2,000 words or so, taking them in probably won’t dent the budget too much, and as a bonus it can really do wonders for these workers’ livelihoods.

However, there’s the underlying case of already having too much of our funds going towards an already oversized civil service. According to a report, we used almost half of the government’s revenue just to pay civil servants and pensioners last year, which means that we only have the remaining half our paycheck to pay for things like development and stuff.

“The size of the civil service has grown too big and become worrisome for a very long time as it continue to increase the government’s financial burden and at the same time, reduces the allocation for development purposes,” – Dr Mahathir, as reported by Straits Times last year.

Until that problem is resolved somehow – which probably won’t happen anytime soon – perhaps adding another 250,000 people to the 1.7 million we already have is not such a good idea right now.

Still, it doesn’t mean that their issues can’t be resolved in other ways. Perhaps the government can take another look at the allegations of shady contracting in the hospitals, or come up with regulations or enforcement to make sure that these workers’ rights are better cared for. Whether or not they will take action and do any of these things anytime soon, however, will remain to be seen.

- 592Shares

- Facebook572

- Twitter4

- LinkedIn4

- Email5

- WhatsApp7