Cloning & sex changes: The bizarre extinction of Malaysian leatherback turtles

- 394Shares

- Facebook367

- Twitter5

- LinkedIn7

- Email6

- WhatsApp9

If you’re older than 20 (anyone?), you might remember that the leatherback turtle has been a frequent mascot for Malaysia. You’d see it in logos and stamps everywhere, and today even on the back of your RM20 note.

The leatherback is the largest of all turtles, capable of growing almost 9 feet in length. Despite its size, it’s a bit of a softy, with a unique leather-like shell instead of the hard shell of most turtles. It can also dive deeper (up to 1280m!), and swim faster (up to 35km/h) than most turtles. All these special features make it an obvious choice for a mascot, since Malaysia was one of the top places in the world to see these amazing animals in their natural habitat.

Was.

Recently, we found out from a casual conversation with Jeeth Vendra, a researcher at TRACC (Tropical Research And Conservation Centre), that the leatherback turtle is considered “effectively extinct” in Malaysia. As divers ourselves, who have seen numerous turtles in Malaysian waters, we were quite surprised to learn this.

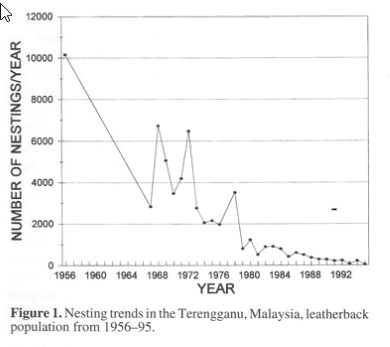

The once healthy total of over 10,000 nests per year in 1956, has collapsed to less than 100 in 1993-95 – “Decline of the Leatherback Population in Trengannu (1996)” by Eng-Heng Chan & Hock Chark Liew

In 1956, there were 10,000 nestings in Rantau Abang, and by 2003 there were only two(!). According to the WWF, despite conservation efforts (and partially because of…), leatherback turtles have been considered functionally extinct in Malaysia since 2007. But we were even more surprised when we learnt HOW these turtles disappeared.

Malaysian leatherback turtle eggs have been changing sex over the years

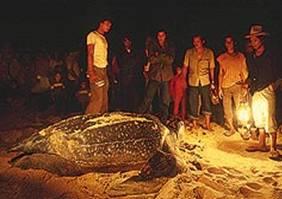

Since the 1960s, Rantau Abang has been known as one of the top sites for leatherback turtle nesting in the world. People from all around the world came to the beach to watch turtles nesting, and conservation of these turtles have existed long since 1949, before Malaya was even established. The Rantau Abang conservation effort was established in 1961.

However, in the 1980s, turtle researcher Professor Chan Eng-Heng and Liew Hock-Chark from Universiti Kolej Trengannu began to notice a strange phenomenon. They were concerned at how nestings were dropping significantly every year.

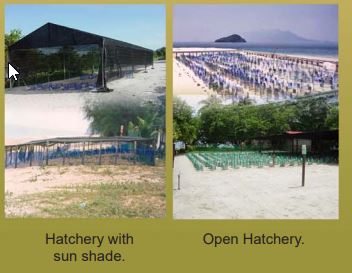

One of the things they found out were that almost all the eggs left to hatch on the beach were female, and similarly, the eggs hatched inside styrofoam boxes in the conservation centre were male.

To be precise, research from other scientists around the world during the 1980s came to a startling discovery… that at temperatures higher than 29.75 Celsius, turtle eggs would be almost 100% female, and that below 29.25 Celsius, they would be 100% male. At a ngam-ngam 29.5 degrees, both sexes would be produced, but not necessarily at a 1:1 ratio. Sadly, temperatures measured of hatcheries in 1990 were at 29.87 degrees, which explains why the majority of eggs throughout the 1980s were overwhelmingly female.

Starting in 1991, turtle hatcheries started shading some of their turtle hatcheries to increase the chances of male hatchlines, but by then, there had already been several cycles of 100% female leatherback releases, and thus a trend of unfertilised eggs being laid on the shores of Rantau Abang.

And sadly, this wasn’t the only threat to turtles in Malaysia.

How Rantau Abang went from turtle central to turtle wasteland

The primarily female hatchlings from Terengganu were just part of an even bigger problem. In 1972, with the advent of trawl fishing, there was already a 21% drop in turtle nestings in the area. Between 1978 and 1980, the drop accelerated to 31%, coinciding with the introduction of Japanese high-seas squid drift nets. Leatherback turtles are particularly affected by fishing not just in Malaysia, but as far as Hawaii, due to their pelagic migratory habits.

At the height of turtle mania in Rantau Abang in the 1980s, up to 1000 visitors would watch a single turtle hatching. Even a Government Reserve for hatcheries opened up to allow vendors to open stalls, cashing in on the turtle craze. In 1991, one radio-tracked leatherback was found to have strayed 20km away from the beach to lay its eggs in peace.

As a diver, I have personally witnessed a tourist lifting up the leg of a leatherback on a rare nesting occasion in Sabah. The resort has since stopped conducting turtle tours in an effort to encourage more turtles to lay eggs on their beaches.

On top of this, consumption of leatherback turtle eggs was common up until the government banned it in 1988. Many other species however, are still open for sale, even in 2020.

And the Malaysian government responded… by cloning turtles?

In a last ditch effort to reinvigorate the local turtle population, the Malaysian Fisheries Department decided in 2007 to set a budget of RM9million to try cloning turtles.

“Once we have perfected the technique, we will apply it to leatherback turtles as they are a more complicated species in the turtle family,” Junaidi Che Ayub, chief of Malaysia’s fisheries department.

However, that was sadly the last we heard of the project. -_-”

What’s even more heartbreaking is that up until today, most of our common sea turtles aren’t even MENTIONED in the Wildlife Conservation Act. Strangely, they mention many species of river turtles and terrapins, but no leatherbacks, no hawksbills, and no green turtles.

Instead, these turtles are mentioned in the Malaysian Fisheries Act.

Thankfully, there are still places with leatherbacks

Let’s be clear about this. Malaysia isn’t the only place with dwindling leatherback numbers. The same things that threatened them here are happening in Thailand, Indonesia, and even the US. From over 115,000 estimated female leatherbacks in 1982, there are as few as 2,300 today.

However, other sites are still recording decent numbers, in the Pacific in Indonesia, Mexico and Costa Rica, and also in Nicaragua, Panama and Guatemala. In west Africa, there are still up to 10,400 nests per season, a number Malaysia hasn’t seen since 1956.

But don’t forget – leatherbacks travel pretty far. Some have even been spotted in Alaska before. As such, with the right legislation, the right beaches, and a little bit of luck, perhaps we can create a home for them once again some day.

- 394Shares

- Facebook367

- Twitter5

- LinkedIn7

- Email6

- WhatsApp9