Eating pork and other horrors Malay labourers faced working at Myanmar’s ‘Death Railway’

- 3.0KShares

- Facebook2.9K

- Twitter20

- LinkedIn18

- Email21

- WhatsApp64

[This article is a translation. For the original, go to Soscili.my.]

World War 2 was one of the toughest periods Malaya was put through. The arrival of the Japanese occupiers turned everyone against each other – some people thought they would be good for them, they thought the Imperial Army would drive out colonial Britain. It did.

When the British fell and left, they left behind a lot of weapons and civilians grabbed whatever they could, using them to do whatever they liked (hunt animals, rob people, etc). So when the Japanese took over they ordered that all stolen goods be returned to their rightful owners, or else…

The streets were strewn with stolen goods the VERY NEXT DAY.

Day by day, Malayan civilians began to realise how crappy the Japanese rule was. Imports stopped coming in, the ‘self-sufficient’ policy was troublesome, and Japanese spies were catching and punishing those who hid rice from kampung to kampung. Everyone was afraid of spies, but neighbour would turn in neighbour just to get more rice as a reward from the Japanese.

So you see how terrible life was? Want to eat rice also cannot. In the middle of 1943, news spread that the Japanese were offering jobs, that the workers would be paid and fed well. What kinda job? They needed labourers to build a railway. This is the extremely heartbreaking story of the men who died building the Burma Death Railway.

Note: A large portion of this tragic true story has been taken from the book Korban Keretapi Maut, by Hashim Yop, who was one of the labourers.

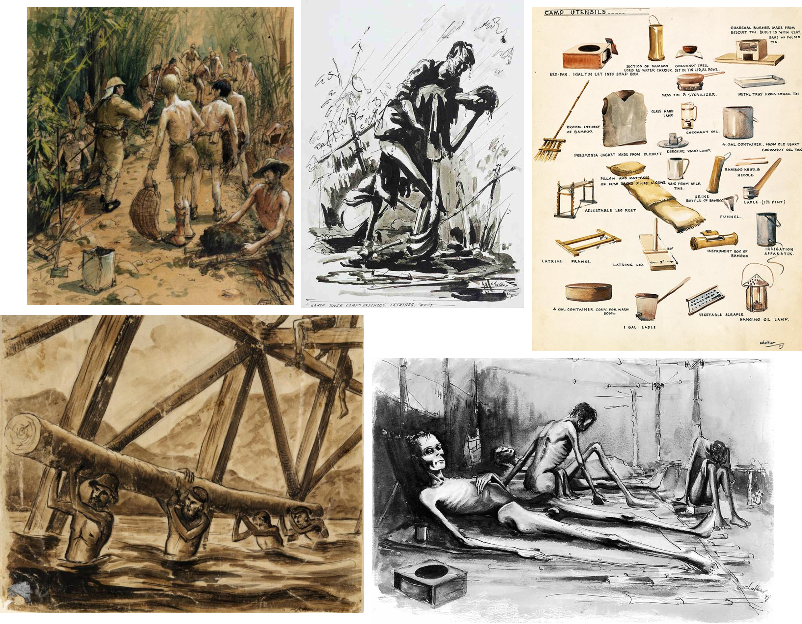

*Some of the following images may be disturbing. Viewer discretion is advised.

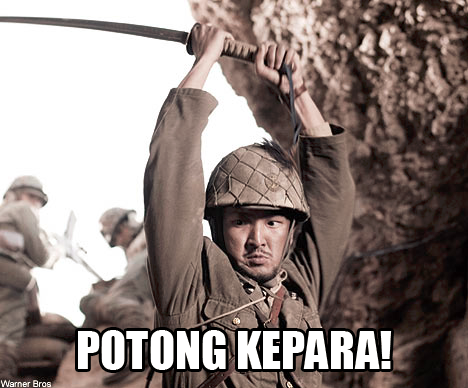

The Japanese said they give nasi goreng udang… but it might’ve been babi

Penghulus registered the names of able-bodied men so that they could be sent to Siam for work. With all the starvation going around and so many people unemployed, everyone wanted the job badly. They submitted the names of those who were ‘useless’, like sampah masyarakat, loiterers and gamblers.

“Approximately more than 180,000 civilians from Southeast Asia and 60,000 Allied prisoners of war (POWs) were deployed to build the railway. Out of that number, around 100,000 were Indians from Malaya and Singapore.” – Chandrasekaran, Chairman of the Death Railway Interest Group, FMT

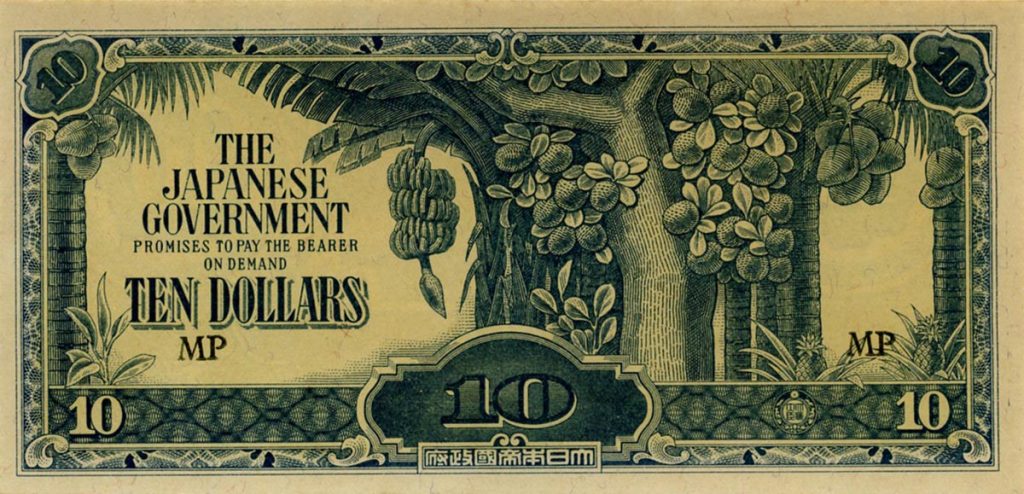

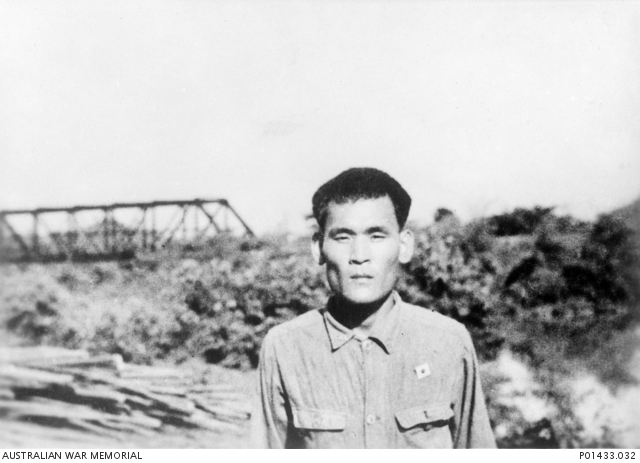

Everyone was assigned to groups, one team had 30 people and a supervisor or ‘koreto’, while the others were known as ‘romusha’, the Japanese word for labourer. Each team was made up of men from the same race, Malays were not mixed with Chinese or Indians or Western POWs, so on and so forth. They were even given 10 dollars worth of banana money to start off.

When the trains arrived, the men were loaded onto the cargo coaches rather than passenger coaches and each one was guarded by a Japanese soldier armed with a rifle. It was cramped and hot. As the train headed north, it made a couple of stops along the way so that the men could eat. When it stopped at Gemas, the Japanese guards instructed two men from each carriage to distribute the food. One guy would be carrying a pail of rice, the other a pail of fried ikan kembung.

The next stop was KL. There, the men received some fried rice that already had lauk. After eating their fill, they discussed that something tak kena about the food. They thought it was prawn fried rice… but the meat wasn’t red like prawn colour… some suspected it might have been pork! In the dark, no one could tell just what is was, prawn, pork, or something else……..

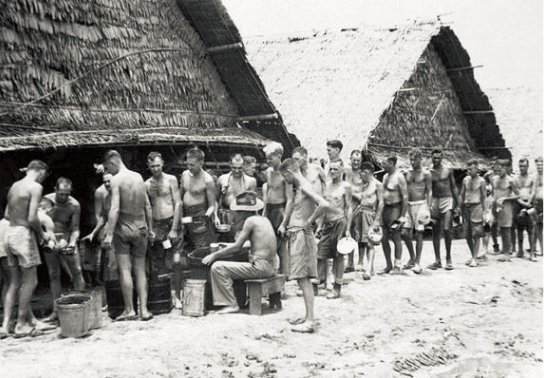

And the rest of their time working on the Death Railway, the workers’ food was terrible. A typical meal was a thin broth of rice and vegetables. Sometimes, they would catch snakes or rodents or lizards in the wild to supplement their meal.

Labourers had their ears, arms and backsides pierced

After crossing the Malayan-Thai border, the train stopped at a few times in Thailand. As labourers sembang with the Thais for a short while, the locals warned them about the fate of those who came before them. Many had died or run away, begging for shelter in Siamese homes. What’s more frightening was when they heard that the labourers would be pierced in the ear, arm and backside.

At last, they reached Bhamphong station and were instructed to form a line and masuk a building one by one. There was an air of apprehension, nobody knew what was gonna happen at the end of the line.

Each labourer was told to come forward and get injected on the arm. Next station, they were injected in the ear. At the exit, they were told to bend forward, where a Japanese soldier stood holding a syringe. As they bent over, a glass instrument as large as a pen with a sharp end was used to inject their anus. Homg the rumours were true!

The meds were for dysentery, smallpox and cholera, but you know what, the jabs didn’t do squat for anyone because many fell horribly sick – dysentery, smallpox and cholera, the whole package, PLUS MORE. Cholera, extremely contagious with a high mortality rate, caused about 12% of labourer deaths. It was one disease the Japanese feared as much as the labourers did, and they provided medication, testing the men with the ‘glass rod’ anal inspection.

“One of the symptoms of cholera is a white stool … This fellow looked down and saw a milk-white motion; and he saw that I saw it. He just gave me a look and it went right through me; it was the look of a condemned man. He knew he had it. He was dead the next morning.” – Ray Parkin, Prisoners of War: Australians under Nippon, quoted on anzacportal.dva.gov.au

Making their way on foot to the work site, the labourers saw so many people lying down. Only when they approached the bodies did they see that they were corpses! A few feet away, the group came across what looked like a pool. The noisy sound of cawing came from inside… they were crows pecking the flesh of the human corpses thrown inside.

Dead bodies were not just strewn on the road, even the latrines were stuffed with corpses! Latrines at the work site were 30-40 feet long holes dug in the ground with bamboo sticks arranged on top so that people can stand and squat over the big hole. They had no walls or roof so there was no privacy and forget about toilet paper. When the latrines were full, the labourers would just dig new holes.

The very sad thing is many sick and elderly men who didn’t have strength any more would sometimes fall into the latrines and die there. Others who didn’t even have strength to crawl to the latrines would relieve themselves wherever they lay.

The Japanese took every chance to slap, kick and punch people. But ironically they respected the dead

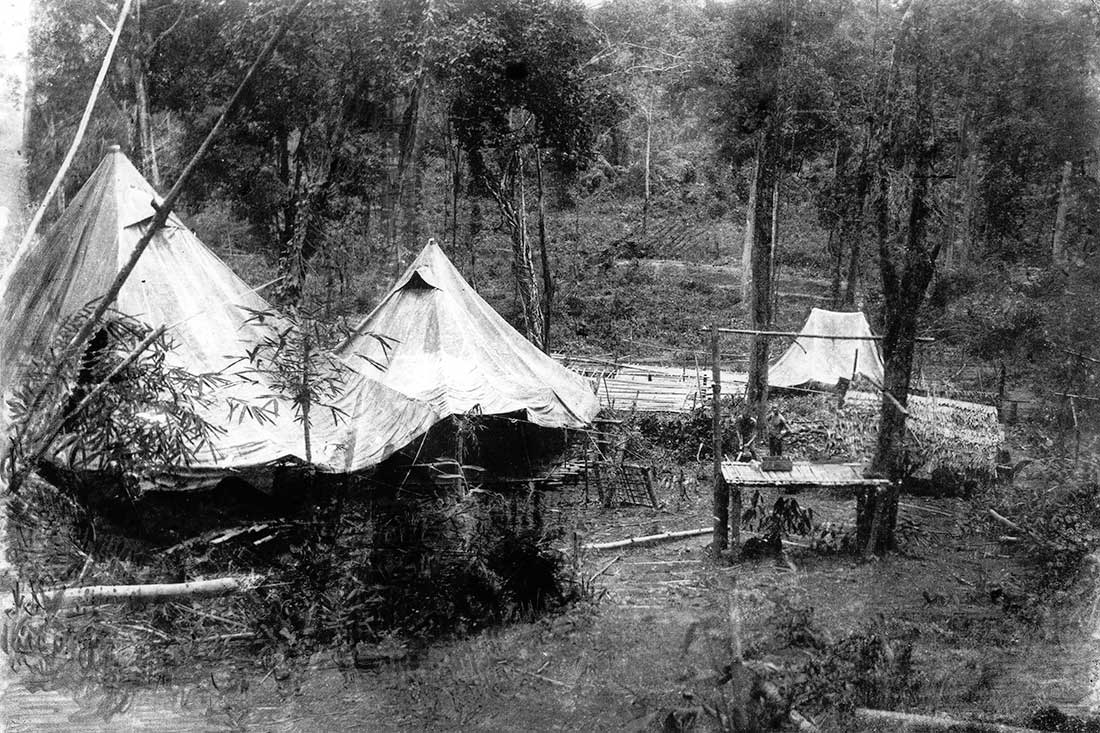

The romusha moved from camp to camp as they built the train tracks starting from Siam moving towards Burma. Their duties every day included digging earth, breaking rocks, chopping trees and pulling heavy logs with rope. That one required 20-30 men. The koreta who oversaw the men had to be ganas with their workers, or else they will kena from the Japanese themselves. A working day… who are we kidding? EVERY DAY was a working day, and work lasted 12-13 hours.

Sadistic Japanese guards watched the men with hawk eyes. Whoever worked slowly or even bent their elbows while pulling logs would be slapped by the guards. That caused many a man to faint or die on the spot.

“It makes me sad, remembering what happened to one of us. He was ill and had headaches, but the Japanese officer did not care. He told the man to get up and go to work. If you didn’t get up, they would hit you. He remained lying down, and a soldier hit him with a bamboo stick. He died.” – Samion Ariff, Burma Railway survivor, Star2

But there was one odd thing about the Japanese… they allowed the burial of dead prisoners, and in some cases attended funerals! Though indifferent to their prisoners’ suffering in life, they respected them when dead. There was one day, all the labourers were gathered in front of a square wood plaque driven into the ground. Japanese soldiers made everyone bow their heads in a moment of silence to honour the dead.

One survivor, S. Shanmugam, whose whole family moved to Thailand to work on the railway, lost his mother when she “died due to shock” (they don’t exactly know the cause of her death). A senior Japanese officer attended his mother’s funeral and even took part in the funeral rites.

“He had a long knife. He came to the funeral. He said, ‘Don’t worry, I’ll be here. I’ll do everything’.” – S. Shanmugam, survivor, Star2

Such insane cruelty. How did they stay sane?

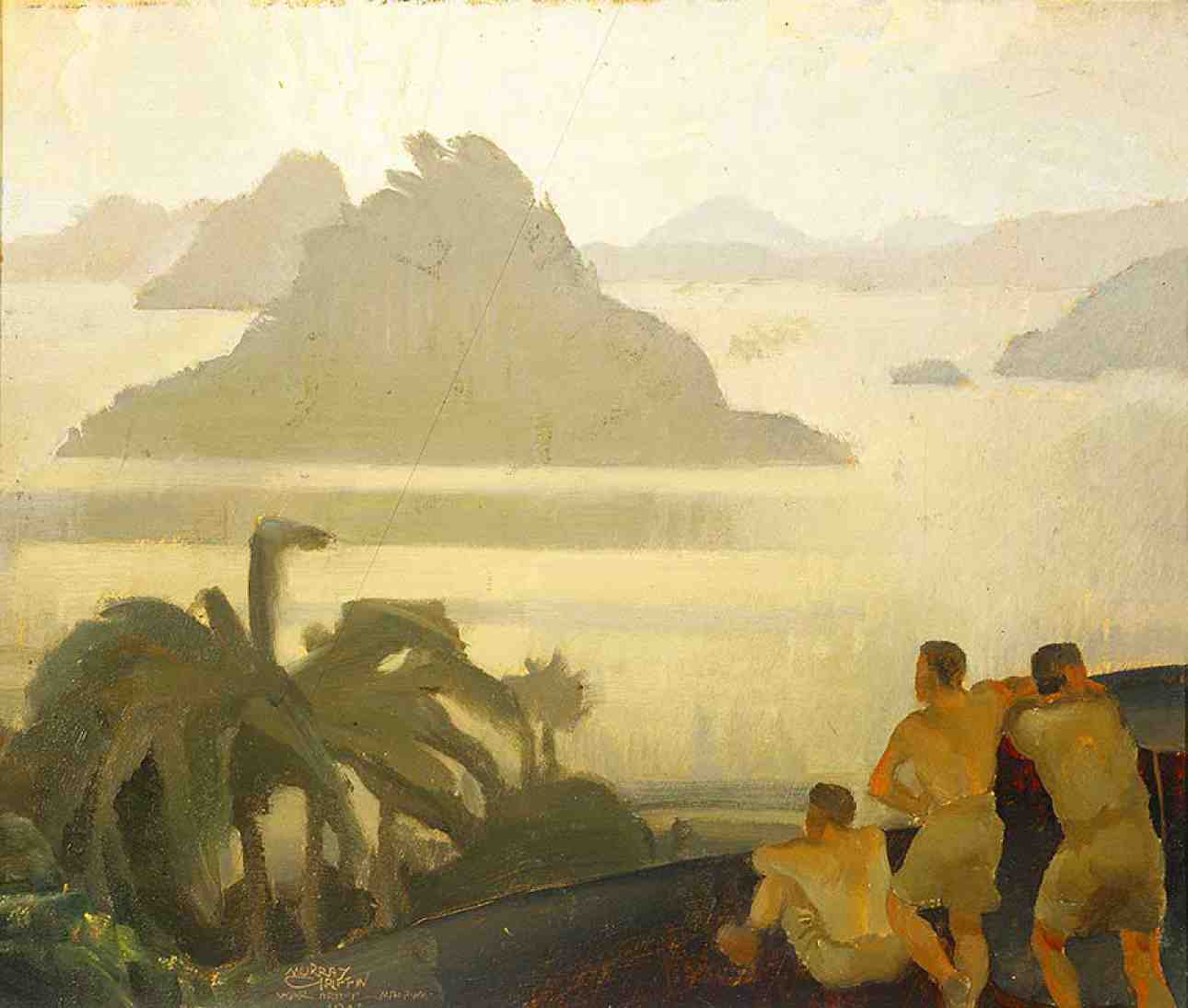

The 415km railway took a quarter of a million labourers about a year to complete – ahead of schedule! That’s an amazing feat considering the extreme conditions they worked under, and without proper tools to boot. Today it is a tourist site.

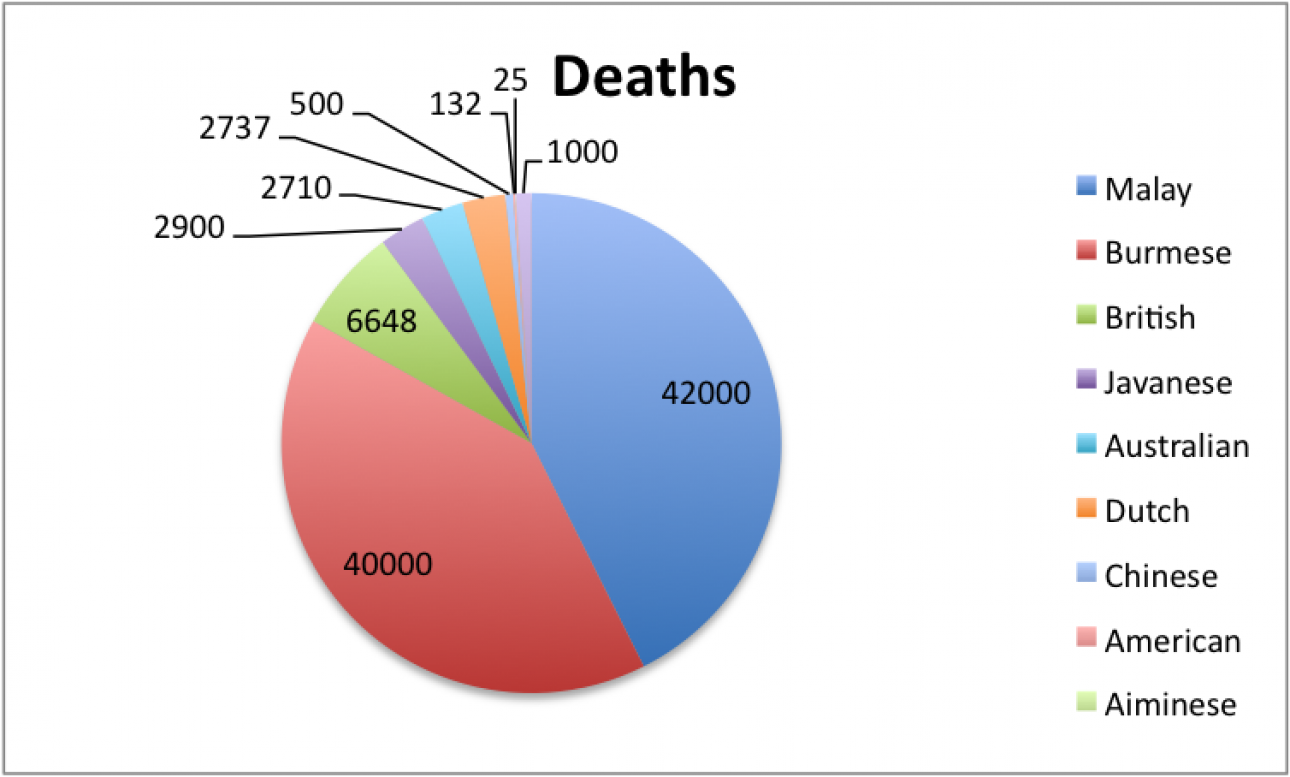

Tragically, about 90,000 civilian labourers and more than 12,000 Allied prisoners died. The majority of deaths were Malays at 42,000, followed by Burmese at 40,000, thirdly, British at nearly 7,000.

In the one year of torture, how did they stay sane? The mental attitude of prisoners affected their chances of survival. Many anecdotes tell of men who died because they lost the will to live. In order to cope, most men surrounded themselves in their own personal armour – for some it was an obsessive sense of duty, for others, humour, or religious faith, and for many, it was setting a deadline: ‘home by Christmas’, or some other date of personal significance.

British artist Jack Chalker was encouraged by camp doctor Sir Edward ‘Weary’ Dunlop to make a record of the horrors, so Jack did so by drawing and painting everything.

Thanks to the artwork and diary records of the labourers, we have the account of the depravity at Death Railway. Men came out hating the Japanese, but there were those who chose not to hold on to bitterness, even meeting their captors after war and forgiving them. If there is any reason to remember, to talk about it, hopefully it’s to ensure mankind does not repeat the horrors ever again.

- 3.0KShares

- Facebook2.9K

- Twitter20

- LinkedIn18

- Email21

- WhatsApp64