Another maid died from abuse in Malaysia, and she probably won’t be the last. Here’s why.

- 1.8KShares

- Facebook1.7K

- Twitter6

- LinkedIn27

- Email28

- WhatsApp77

[Article updated 22nd March 2018]

We’ve recently came across news of a Datin who escaped jail time with a good behaviour bond of RM50,000, even after abusing her maid with various weapons and causing injuries to her head, hands, legs and internal organs. (Pic of the victim, Suyanti, above left.)

And earlier this year, an Indonesian maid had to be rescued from her employer’s house in Bukit Mertajam, Penang. Adelina, 21, had been forced by her employers to sleep outside the house for at least a month, sharing a porch with a black Rottweiler before she was rescued last week. She was taken to a nearby hospital, but she died soon afterwards. There were burn marks on her legs that were oozing pus, as well as various other injuries.

“There was swelling on her head and face as well as injuries on her arms and legs. Attempts to record her statement when she was still alive were not successful as she was still in fear,” – Asst Comm Nik Ros Azhan Nik Abdul Hamid, Central Seberang Prai OCPD, for the Star.

It would seem that Adelina received both repeated physical and mental abuse, as evidenced by her fear of speaking up as well as her terrified reaction when found by the rescuers. Following that incident, her employer, a 36-year-old woman, her brother (39) and an elderly woman (60) were detained and are being investigated under Section 302 of the Penal Code for murder.

While Adelina’s case is a tragic one, it’s not by far an isolated incident. Throughout the years, Malaysia had recorded quite a few cases of maid abuse.

Malaysian employers were so abusive, Cambodia had banned its maids from coming here.

Foreign maids in Malaysia may come from one of 13 different countries in Asia, but the majority of them are Indonesians, Filipinos and Cambodians. The abuse of Cambodian maids had once been so rampant that in 2011, Cambodia banned their maids from ever coming to Malaysia, due to them receiving physical and sexual abuse, forced overtime, unpaid wages, and unhealthy meals. That ban was lifted in 2015.

“Maids from Cambodia in particular have faced the brunt. Lots of them have returned to their country in body bags,” – Charles Santiago, Klang MP, for FMT.

In 2012, a Malaysian couple starved their Cambodian maid to death. Mey Sichan, a 24 year-old-maid, weighed only 26.1 kgs when the police found her in her employer’s residence, which was coincidentally also in Bukit Mertajam, Penang. Upon examination, her body was marked with 29 fresh and old injuries, and she died from a hole in her stomach from not eating enough and constant abuse.

Maids from other countries are abused as well. Migrant Care, an Indonesian-based NGO, had stated in 2015 that 50 cases of abuse happens annually to the 300,000-ish Indonesian maids in Malaysia, but that’s just the reported amount. They estimated the actual number to be closer to 1,000 cases per year.

Perhaps that’s why it’s not at all hard to find cases of Malaysian employers abusing their foreign maids in the news. From being prevented from cleaning themselves to having their teeth pulled out using sharp objects to being intentionally scalded by boiling water and burned with an iron, there’s no shortage of stories, and after a few of them you might notice that a lot of them had Malaysians ‘in shock‘ or ‘outraged‘.

Some of these cases stretched as far back as 2004, so why are horrific instances of maid abuse still happening up until last week? Most people probably won’t think about this, but…

The jobs (and consequently, lives) of foreign maids aren’t protected by the law

If we felt that our bosses are treating us unfairly, most of us might turn to the Employment Act 1955 to see if we have to work on a public holiday or whether we’re entitled to any benefits like overtime and stuff. Maids also have a section specifically for them in the Act, and it sounds something like this:

“57. Termination of contract

If either you or your boss don’t want you to work there anymore, either of you have to tell the person you’re firing/leaving 14 days in advance, or pay the other person 14 days worth of wages.” – Much simplified (and possibly inaccurate) excerpt from the Employment Act 1955.

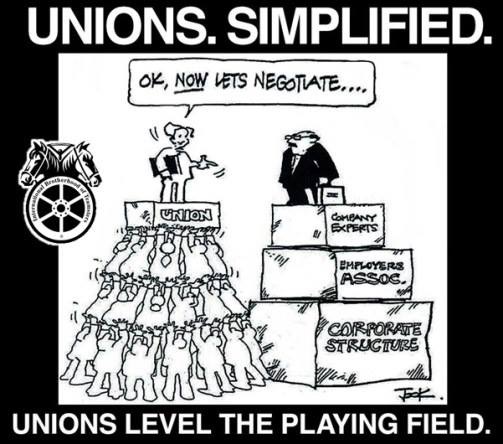

And that’s about it. Although domestic servants are specified as employees, they don’t receive any of the benefits under this Act except for a 14 days’ notice when they want to leave the job or are fired. This basically means that the other stuff, like working hours, days off, and maternity leave are all up to their employer’s discretion. Charles Santiago, the Klang MP, had said that this laxness in labor laws is one of the reasons why Malaysians tend to abuse their maids.

“We treat them like slaves by making them work 24 hours a day instead of thinking of them as employees. Ensuring that labour laws cover the rights of housekeepers is something that we should really push the government to look into.” – Charles Santiago, Klang MP, for FMT.

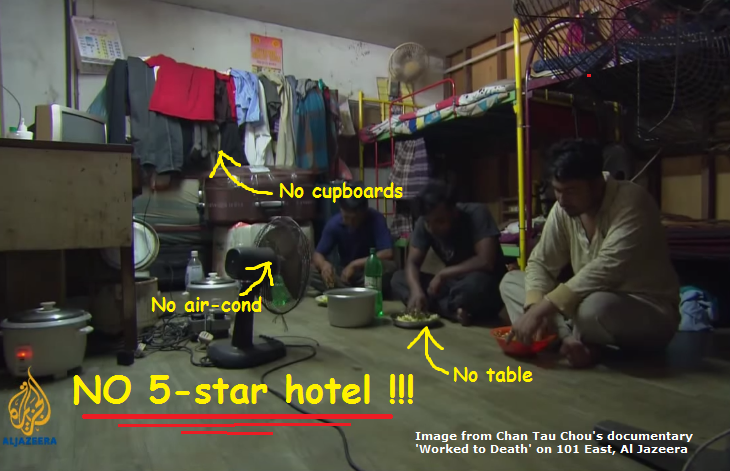

Back in 2004, the Human Rights Watch had already expressed its concern on legislation that excludes domestic workers from legal protection, saying that many of the maids work 18 hours a day, seven days a week, and they are often not paid. In their report, some of the maids complained about being allowed less than 5 hours of sleep at night and being prevented from either leaving their employer’s home or contacting their families.

Things weren’t much better a decade later. The International Labor Organization (ILO) and UN Women did a survey in 2016 among Indonesian and Filipino maids in Malaysia, and a quarter of them have no rest days and work an average of 14.4 hours a day.

Other causes had been attributed to why Malaysian employers tend to abuse their maids, such as frustration at the maid’s lack of training due to differing cultures and the classification of domestic workers in the Employment Act as domestic “servants” or “maids”, leading employers to assume a master-servant relationship with their maids. However, if the situation is to change, ultimately the laws will have to be amended to protect these workers.

So why aren’t the laws amended yet?

In light of recent events, some groups have again pushed for laws that protect maids from abuse.

“Why are we letting this happen again and again? … We seriously need to address the root cause of why employers feel it is perfectly normal to abuse a domestic worker. There needs to be effective policies and legislation to protect maids like Adelina from abusive employers,” – Glorene Das, Tenaganita director, for NST.

But the new laws have already been drafted… and stayed in draft form for several years already. Even then, the ILO and UN Women had stated that the drafts they have seen are far from meeting international labor standards. And even though Malaysia have been employing a large number of domestic workers for the past decade, we have yet to ratify the ILO’s Domestic Workers Convention 2011, which protects the rights of domestic workers.

A reason for that may be that there is a view that such laws are unnecessary. In 2004, Azmi Khalid, Malaysia’s home affairs minister at that time, had said that there will be no move to change the law to specifically protect maids. The reason given was that the number of maids who suffered abuse were less than 1%.

“Maids are very personal and they are part of the family. The normal law is enough if there is a report of abuse,” – Azmi Khalid, as reported by BBC.

There had since been no new laws, but there had been other efforts to combat the problem. Last year, the ILO and the Ministry and Human Resources published a guidebook on the treatment of domestic workers. That link is dead and we can’t find the guidebook anywhere online, but it advises employers to treat their maids better, like giving them a day off and agreeing on salary, home leave, job scope, insurance coverage and other matters. However, the guide isn’t legally binding, so it’s more of a suggestion rather than a law.

In November last year, Malaysia and Cambodia signed an MoU that aims to protect Cambodian domestic workers from abuse. Among other things, according to the agreement the new wave of maids coming in will each be given a free smartphone and a personal bank account so that the authorities can monitor whether the maids are being abused or if they are not being paid. While it’s still too early to see the results of this initiative, some labor groups are doubtful as to whether the MoU will really be enforced as none of the maid agencies in Cambodia were informed of it.

Regardless of initiatives, the protection of maids is a serious issue, as…

Malaysia desperately needs maids, because we’re scaring them away

If you’ve employed maids for some time now, you might have noticed that it’s costing more and more to get one these days compared to back then. This is because the number of maids coming in have been dropping for some time now. According to the Malaysian Association of Foreign Maid Agencies, a decade ago there were about 300,000 registered domestic maids in Malaysia. In 2016, the number had dropped to less than 200,000, and last year, the number barely went over 130,000. In short, agencies are running out of maids to hire out.

This is partly due to Indonesia, the Philippines and Cambodia, countries from where most of our domestic workers come from, have been banning and restricting their domestic workers from coming here, probably because of all the abuse stories going around on their media. This is a huge problem, as maids have became an important part of many Malaysian households. As put by J. Solomon, the secretary general of the Malaysian Trade Union Congress (MTUC),

“Where would Malaysian couples be, especially where both spouses work, if we did not have these maids to take care of our homes, our children and our elders?” – J. Solomon, for the Malay Mail Online.

While the laws that protect domestic workers like Adelina from abuse may not come anytime soon, maybe we can prevent more cases like hers if we are all a bit more kaypoh about maid abuse.

If you suspect that a maid is being abused (by bruises, by them looking scared or by them obviously being forced to sleep outside), the Women’s Aid Organization (WAO) recommends calling the police through the Maid Abuse Hotline (yes, that’s a thing) through the number 03 – 2052 0999. You can remain anonymous for this purpose, and just provide an address where you suspect the abuse took place. The police will come and interview the abused maid and take the necessary steps.

If you can’t go to the police for whatever reason, you can also call women’s organizations like Tenaganita (012 – 339 5350) or WAO (03 – 7956 3488), who will help report the abuse and provide a place for the abused maid to stay during the ordeal.

- 1.8KShares

- Facebook1.7K

- Twitter6

- LinkedIn27

- Email28

- WhatsApp77