Forget rubber and tin. The British actually got rich from the opium trade in Malaya.

- 39.1KShares

- Facebook38.5K

- Twitter47

- LinkedIn42

- Email87

- WhatsApp358

If you grew up with Malaysian TV, chances are you’ve seen one of the many, many reruns of P Ramlee’s parody of the Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves story. So you might be familiar with this scene (15:50):

In case you couldn’t watch the video for some reason, it’s the scene where Ali Baba’s servant went to a bazaar, where traders blatantly shouted out the kind of drugs they were selling (in this case, marijuana and opium) to attract customers. However, when the servant tried to buy some belacan (shrimp paste), it had to be done discreetly as unlike marijuana and opium, belacan wasn’t licensed.

While some may theorize that this scene was a clever jab at misplaced laws, barring the Arabian motif, that scene probably wasn’t as surreal as you might think. Up until 1946, opium was more or less legal in Malaya, and you can literally go to a shop and get some like you would with a McFlurry. And just like a McFlurry, you’ll also get the option to either smoke there or dabao.

“Bah!” We hear you say. “We know already! Sejarah books got mention opium in British times …right?”

We’re not sure if the books mentioned opium, but they sure as heck didn’t mention the sheer significance of it. Opium was such a big part of Malaya’s history that if we take it out of the picture, Malaysia might look very different today. Industries like tin mining or pepper planting might not have gotten very far, and the British probably won’t be able to afford all those expensive-looking colonial buildings and military bases.

Because while tin mining and spice growing might have been touted as big moneymakers in the British era, on average…

Roughly HALF of the British’s yearly revenue in the Straits Settlements came from opium

If you’re unfamiliar with the drug, opium is the dried latex from the opium poppy, which is also where morphine and heroin come from. The British’s history with opium is pretty fascinating: they practically forced farmers in India to plant the opium poppy so they can have a powerful trading item, and they got the Chinese addicted to the drug just so that they can get tea from China without losing money. And fought two wars to keep it that way.

So with that in mind, it would actually be surprising if there’s no mention of opium (aka candu) in our local history. Opium wasn’t just a hobby back then: it was a hyucking massive industry. To give you an idea of how big opium was, for every year between 1819 and 1919, opium money contributed between 30-60% of the British’s locally collected revenue in the Straits Settlements, averaging at around 40-50% every year.

In the beginning, the British didn’t actually sell the opium themselves. To save on administrative costs, some colonial governments auctioned off the right for other people to collect tax on their behalf or hold a monopoly on items like opium and liquor. This practice is called ‘farming out‘, and monopolies were called ‘farms’, like alcohol farms and opium farms. It doesn’t mean they were growing alcohol or opium, but they merely held the monopoly for the business.

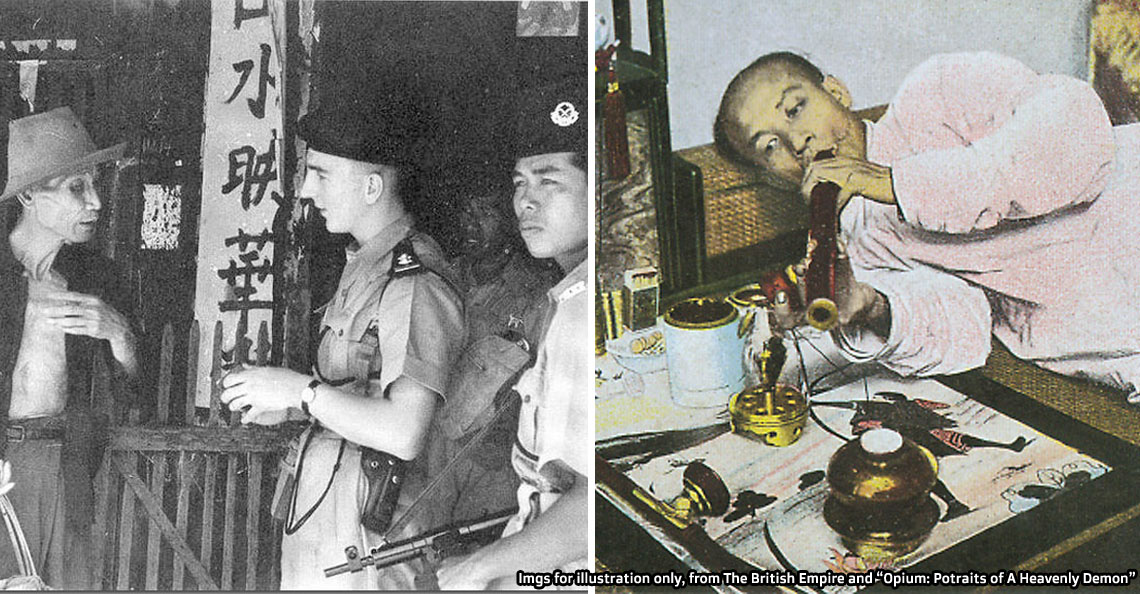

In the case of opium farms, the ‘farmers’ (the monopoly holders) will provide his own men to import the opium, distribute and sell it within his territory. They may also hire ‘chinteng‘ or opium police to make sure that opium from other territories were not smuggled into their turf, and all these hiring became part of the cost of holding an opium farm.

A portion of the farmer’s profits will be used to pay the government for the privilege of holding the monopoly, after taking out rent, overhead, costs and all the other shenanigans involved in importing, processing, and selling opium. So imagine how much opium and money exchanged hands for those tiny shares of the profit from all the opium farms to add up to about 50% of the Straits Settlements’ total revenue every year.

And because of the way opium farming worked, it wouldn’t be an exaggeration to say that…

Businesses like tin and other commodities can only work with opium

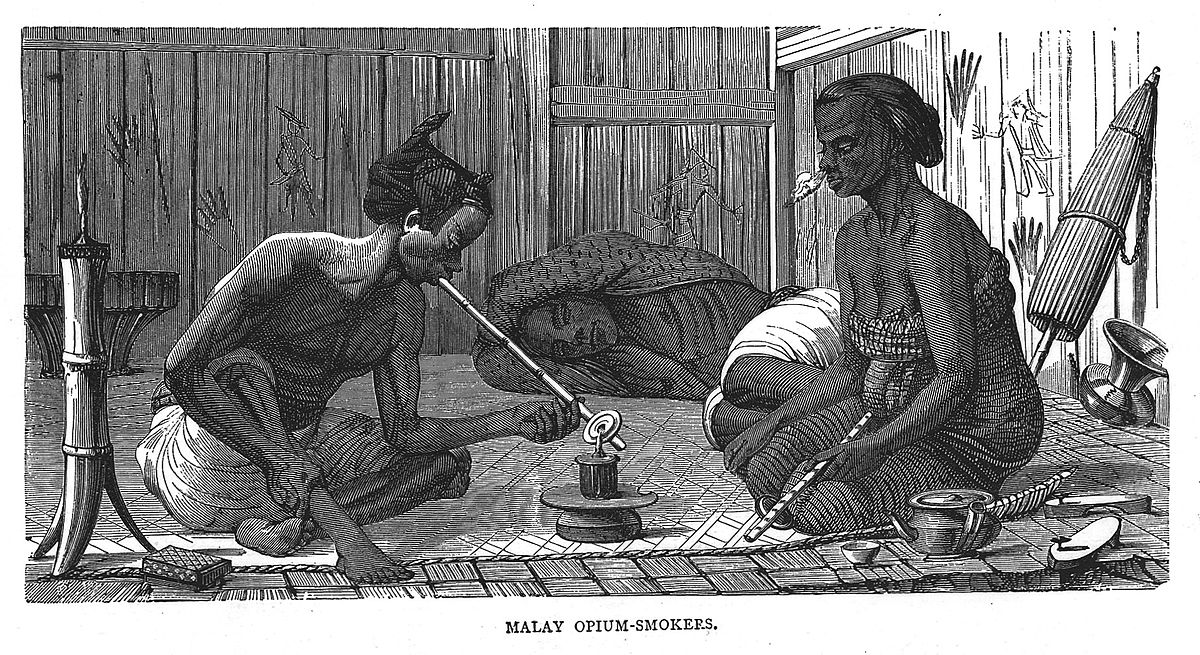

Much like prostitution (which we covered in a previous article), the demand for opium seems to be fueled by a mass influx of Chinese migrant workers in the latter half of the 19th century. While people of all races and classes were known to partake in this smoky treat in colonial Malaya…

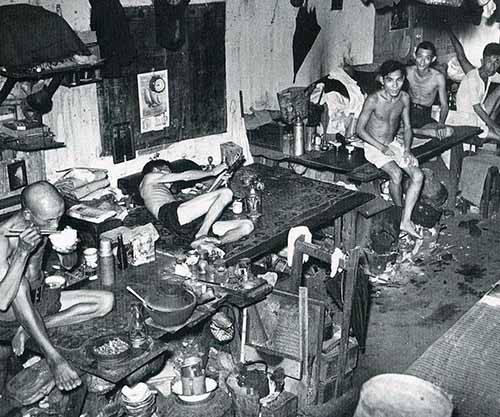

…the main customers before 1900 had been Chinese migrants, who reportedly got addicted to opium in Malaya instead of being already addicted when they came here. It’s not hard to wonder why these laborers would consider opium: breaking your back mining tin in a foreign land with no Socso wasn’t exactly fun. Opium blunts both the mental and physical fatigue of these workers, allowing them to keep working for a few hours more after the day’s end after a short puff.

“I… have seen thousands and thousands of Chinese miners working in swarms at tin mines, displaying physical energy and endurance that the white man, under similar conditions, could not have and apply, and at the same time keep his full health… after working all but naked for hours together in water up to their knees, [they] go back to their quarters, and… smoke a pipe or pipes of opium apparently without prejudicial effect…” – John Anderson, a Singaporean merchant, as quoted in the Journal of Southeast Asian Studies (2002).

Because tin miners back then also probably don’t get dental and medical, opium was also used as a painkiller and a medicine for all sorts of diseases, like cholera, dysentery, fever, beri-beri, and probably a lot more. While smoking opium probably didn’t cure all these diseases, it did get a lot of people helplessly addicted to the drug… which was actually a favorable thing to the opium farmers.

Back in the day, most opium farmers (who were almost exclusively Chinese in Southeast Asia) also held another business on the side. In Johor and Singapore, opium farmers usually also own a pepper or gambier business, and in Perak and Selangor, they may also own tin mining operations. If there was no opium business going on, these commodity businesses would barely break even on the international market.

However, bring opium into the equation, and you can severely cut the labor cost. You get your workers addicted to the opium you sell, and most of what you pay them will go right back into your pocket. While a lot of these Chinese laborers came to Malaya to save up enough money to go back to China and start a new life, so strong was the pull of opium that many fell into a cycle of addiction and debt.

“Opium-smoking throws whole families into ruin, dissipates every kind of property, and ruins man himself… When the smoker has pawned everything in his possession, he will pawn his wife and sell his daughters.” – a description of an opium smoker, taken from “The Land and People of China“.

So while opium did wonders for Malaya’s economy, it was a bit hard to ignore the negative aspects of the trade. So perhaps surprisingly…

Despite mounting pressure, opium was only completely outlawed in 1946

While in the beginning the primary users of opium had been Chinese coolies and mine people in the rural areas of Malaya, the economic boom that it brought expanded those backwater places into towns and urban areas. The customer base grew, and opium made their way into the lungs of rickshaw pullers, dock laborers, mild-mannered craftsmen, and basically anyone who cared for it. By the 1930s, it was said that out of every four Chinese adults in Singapore, one was an opium addict.

Opium farm owners, who were exclusively Chinese, became the wealthiest and most powerful people in their communities at that time, but things soon declined. The government eventually abolished the farming system and turned opium into a government monopoly by 1907. That was also around the time that people began to seriously question the government allowing opium to be available so freely.

Some of the higher ups in the British government felt that the practice of collecting revenue from opium was a dirty one. For instance, in the 1920s the British in the Straits Settlements wanted to build a military base in Singapore, but Leopold Amery, the British Secretary of State for the Colonies, had pointed out that a large portion of it will be built with ‘tainted money’.

“…already between 40 and 50 percent of the military contribution [of the Straits Settlements] is derived from the sale of opium… [and] the Imperial Government [is] thus drawing… from what it is committed to regard as a tainted source.” – Leopold Amery, in a 1927 letter, quoted from “A Genealogy of Tropical Architecture“.

The timing of the government monopoly had also coincided with the rise of anti-opium groups in Malaya, who pressured the government to not be so loose with the opium. So after a few conflicts and fact-finding commissions, plus mounting internal and external pressure, a series of restrictions was finally put on the sales and use of opium in the Straits Settlements.

The Japanese invasion came and went, and in 1946, the British Military Administration took over and passed a proclamation that made opium, its products, and the tools to make and smoke them totally illegal. And the rest is history.

Knowing what we know now, it might seem weird that…

For such a big part of our history, opium wasn’t mentioned much

There’s a famous saying that goes something like ‘history is written by the victors‘. Although who said it and for what is up for debate, the meaning is clear: whoever is left standing gets to choose which parts are great and should be included in the story, and which parts are unsavory and should be downplayed or left out completely.

This seems to be the case in Malaysia, where some unsavory parts of our story, like prostitution and slavery, have not been part of the version taught in schools. Opium, while mentioned in passing, got its significance severely understated.

But why should it matter? After all, a lot of us can probably do with not knowing that the pretty colonial buildings we see today were partly built using money from hopelessly addicted tin coolies. Well, there’s another saying about history, one that was actually taught at the very beginning of the syllabus: those who can’t remember the past are condemned to repeat it.

Knowing the darker parts of our history is just as important, because if all that we remember of our past were how clean we were, how will we stop ourselves from making the mistakes we’ve already made in the future?

[If you enjoyed this story and want more, please subscribe to our HARI INI DALAM SEJARAH Facebook group]

- 39.1KShares

- Facebook38.5K

- Twitter47

- LinkedIn42

- Email87

- WhatsApp358