Here’s what the gomen can do if you APPEAR like you’re homeless

- 877Shares

- Facebook837

- Twitter7

- LinkedIn2

- Email8

- WhatsApp23

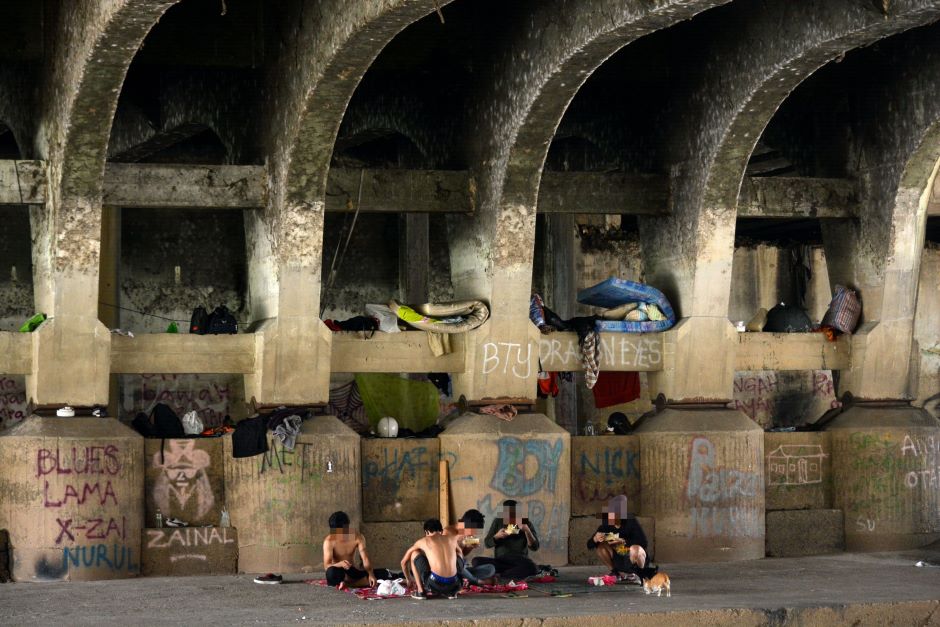

It doesn’t take a genius to notice KL’s homeless problem – each night, dozens of people take refuge wherever they can on the now-empty city streets, sheltering themselves as best they can from the elements until morning (or the authorities) come.

It’s hard to estimate the numbers, but this February 2015 article quotes Segambut DAP MP Lim Lip Eng saying there were between 1,500-2000 of them in the city, according to DBKL (if you have more up-to-date stats, please mention them in the comments!). Hard enough being homeless; people are always calling you lazy and shooing you away from public places. How like that?

It’s easy to shake your head and say things like “See lah this gomen, what are they doing about all these homeless people?” and then go about your biznez. But the truth is our government is doing something – it’s the Destitute Persons Act 1977. To make things easier, we’ll just call it DPA.

The DDPA is a law that allows the minister in charge (the Minister for Women, Family and Community) to “establish and manage welfare homes and make any rules relating to the care, control, discipline and rehabilitation of persons residing therein.”

In other words, its a law that pretty much gives the gomen the power to do whatever they need to do to help homeless people, in theory. (Here’s a handy little cheat sheet courtesy of our friends at Poskod.my)

Sounds good right? But as with most laws in Malaysia (see: the POTA, NSC, the OSA, the Sedition Act, etc) the truth goes a little deeper than that. Here are a few things you need to know about the DPA:

1. Anyone with authority can take you away if they even SUSPECT you might be homeless.

Really wan. Here’s how the law defines a ‘destitute person’:

“(a) any person found begging in a public place in such a way as to cause to be likely to cause annoyance to persons frequenting the place or otherwise to create a nuisance; or

(b) any idle person found in a public place, whether or not he is begging, who has no visible means of subsistence or place of residence or is unable to give a satisfactory account of himself.”

Wait wait wait, so even if someone ISN’T begging or being a nuisance, he can be hauled off? Not cool bro. Somemore the law goes on to say that:

“Any officer duly authorized in writing by a local authority and acting under the direction of the Director General or any social welfare officer may take into his charge any destitute person and produce such person before a Magistrate within twenty-four hours”

… which basically says that any Ali, Ah Seng or Muthu can be given the authority to do this. Scary or not? Well it gets worse.

2. You can get locked up for up to THREE YEARS, just for being homeless.

“Through the DPA, Social Welfare Ministry officers are given the power to arrest anyone they suspect of being homeless,” explains Rayna Rusenko, a policy researcher who investigated the system in depth for her thesis. “Such people are automatically remanded at Pusat Sehenti [Halfway Houses], with no access to a lawyer. Then, after 30 days, the Ministry may decide to send the person to Desa Bina Diri for a sentence of three years, which may be renewed once, again at the discretion of the Ministry.”

Desa Bina Diri are institutions set up by the Ministry of Social Welfare to, in their words, “care for, protect and rehabilitate the homeless so that they may become productive, and acquire the skills and positive attitude necessary to be reintegrated into society.” There are five of them throughout Malaysia right now, but the thing is…

3. The facilities and services they provide aren’t quite as advertised.

Thanks to her studies, Rayna was granted access to observe the institutions involved in the system. The following is the description of a Pusat Sehenti that appears in her Master’s thesis:

“At Pusat Sehenti Desa Bina Diri in Sungai Buloh, for example, male detainees are locked into a large cage-like room with bars instead of walls, and chains on the door, and not permitted to leave that room at all for the first week of remand. There are no barriers for privacy and all persons must eat, sleep, pass time, and use the bathroom together in the same room.

Respondents reported that incidents of incontinence were regularly ignored by staff, leaving persons in the room with little choice but to make attempts at cleaning, or physically separating themselves from, soiled areas. The heat of the room, as well as close proximity to other persons, also contributed to the spread of infections and skin diseases.”

4. The only way out is to be released – or to escape.

A spokesperson from the Ministry of Social Welfare told CILISOS.MY that residents can be released if they meet one of two conditions:

- Either their supervisor is satisfied that the resident can get a job and take care of himself, or

- the resident is released to the care of someone — like a family member — who can support him.

We were also told that “the Ministry always strives to provide the best service it can to these residents.”

Rayna begs to differ. “I spoke to five former detainees of Desa Bina Diri. One explained to me that food was often rotten, and there was extreme illness and some deaths in the facility, which was frightening for him. He was there for over a year before escaping.” This Malay Mail Online article also has video which shows detainees at Pusat Sehenti Sungai Buloh begging to be released.

5. Many of those detained under the DPA have some sort of mental illness.

When we asked, a spokesperson from the Ministry confirmed that as of February 2016, 35 per cent of residents have some sort of mental illness. “Those who stay with us are the ones who can be controlled with medication,” the spokesperson says. “Those who exhibit more aggressive behaviours are referred to nearby hospitals for treatment.”

Given the conditions described above, those of us without pre-existing conditions also can go a bit nutty – so what about those who already live with some form of mental disorders? Rayna’s report on Pusat Sehenti Sungai Buloh found that numerous respondents either saw or experienced pronounced psychological anxiety or declining physical health immediately after entering (you can read a short version of Rayna’s thesis here).

6. This isn’t a new problem.

While visiting the Pusat Sehenti at Sungai Buloh, Rayna was asked not to take any photos. “I was told by the superintendent at the time, Shamsuri bin Sulaiman, not to take pictures because, as he voluntarily explained, he experienced trouble in the past when photographs of Taman Sinar Harapan in Kuala Kubu Baru, which I believe was under his direction at the time, were released to the press and resulted in a scandal.”

In fact, you can find mentions of Desa Bina Diri and the DPA as far back as the October 4th, 1981 edition of the New Sunday Times.

The Coalition of NGOs also released a statement on this back in 2014:

‘The policies do not resolve structural issues faced by the homeless community. It is an effort to hide socio-economic failures and problems.

“The ‘saviour mentality’ type solution aiming to ‘rehabilitate’ members of the community is wrong, inhuman and arrogant,” said Michelle Yesudas of Lawyers for Liberty.

She added that imprisoning the homeless for up to three years (or more) eerily echoes the Internal Security Act’s (ISA) policy of detention without trial.

“This act criminalises a person’s existence,” she stressed.’

You can read the full statement from the NGOs involved at the time on SUARAM’s website.

“Uh… I’m not homeless also. Why should I be worried?”

Because if the government can use the law to harass and police citizens who don’t have a voice, all in the name of ‘social welfare,’ then it’s not a stretch to believe that our other laws can be misused to take away the personal rights and freedoms of other groups – maybe even you and those you love.

Perhaps this statement from NGO Food Not Bombs says it best:

“People who are homeless face a multitude of troubles such as illness, injury, job exploitation, debt, and discrimination, yet practices linked to the DPA only add further strain to their lives by depriving them of possessions, personal dignity and well-being and constitutional rights and freedoms.

Policies and programmes for addressing homelessness should—without exception—be designed in accordance with the equal rights, freedoms, dignity, and needs of all citizens. We cannot fight homelessness by trampling on the rights of persons experiencing poverty and homelessness.

There are things you can do about it, though. Firstly, you can always educate yourself about alternatives to the DPA with this fact sheet. Spend some time getting to know people living on the streets and understanding the issues surrounding homelessness by volunteering (we suggest any one of these stellar organisations).

Or even simpler – just smile at the next homeless person you see on the street — it doesn’t cost you a thing to be a nice person! 🙂

—

These are just some of the tales you’ll find in GILA, a new book that explores the mental health landscape in Malaysia through the personal stories of those living with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, anxiety and depression, as well as those who love, care for, work with and advocate for them. GILA will be launched this May 14th, 2016. Find out more at https://www.facebook.com/events/591685614340289/.

- 877Shares

- Facebook837

- Twitter7

- LinkedIn2

- Email8

- WhatsApp23