How the mysterious death of an auditor in 1983 led to Malaysia’s first banking scandal

- 8.3KShares

- Facebook7.2K

- Twitter121

- LinkedIn62

- Email165

- WhatsApp728

If you enjoyed this story and want more like this, please subscribe to our HARI INI DALAM SEJARAH Facebook group ?

If you were to say the words “Financial scandal” in Malaysia today, chances are pretty high that you’d get “1MDB” in response.

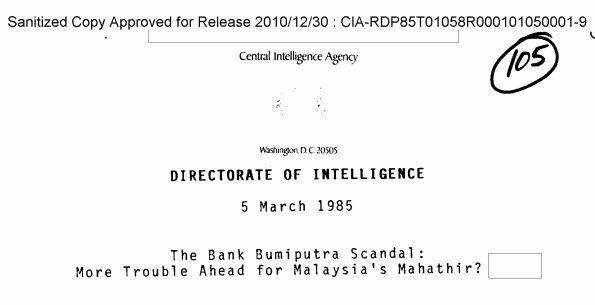

But what if we told you that Malaysia was involved in another international financial scandal almost 40 years ago – two years after Dr. Mahathir became Prime Minister – that involved the death of an auditor sent to investigate the case? And, just like 1MDB, the United States government also conducted an investigation on it… an investigation that was made available online in January this year.

So how big was this scandal, and why was someone killed over it? Was Dr. Mahathir involved?All this and more will be answered once we head back to 1979, when…

… Bumiputra Malaysia Finance gave a massive loan to a Hong Kong company

(Note: We’ll be using RM for familiarity even though it was known as the Malaysian Dollar in those days)

In 1965, the government established Bank Bumiputra Malaysia Berhad (BBMB) in order to help Bumiputras get more involved in economic activities. BBMB’s first chairman was Tengku Razaleigh, who later became Finance Minister ← This part is important for later.

Bumiputra Malaysia Finance (BMF) was set up in 1974 as a subsidiary of BBMB and started operating in Hong Kong in 1977. By 1980, BBMB was receiving RM50 million a month from Petronas to increase their reserves, eventually making it the second-largest bank in Southeast Asia at the time.

Due to the property boom in Hong Kong in the late 1970’s, a bunch of this money ended up there in the form of loans approved by BMF. The main recipients of these loans was a company called Carrian Group. Originally established as a pest control company by a Singaporean engineer named George Tan, Carrian Group was ballin’ in the early 80’s – involved in a whole bunch of businesses from shipping to catering, across multiple countries.

But what gave Carrian Group legen….wait for it… status was when George Tan bought a super-premium commercial building in HK called Gammon House (now known as Bank of America Tower) for HK$1 billion in January 1980 and sold it less than a year later for HK$1.6 billion! This, along with skyrocketing share prices, made George Tan Hong Kong’s corporate golden boy overnight; much like Leo DiCaprio’s character in The Wolf of Wall Street.

But just like The Wolf of Wall Street, George Tan’s high roller status didn’t last long. Y’see, Hong Kong was a British colony and, by the 1970’s, China wanted Hong Kong back. The intensified negotiations between the British and the Chinese in the 80’s created a sense of political uncertainty and fear in the population which led to a massive collapse of property prices in Hong Kong in 1982. This in turn affected the Carrian Group and, by 1983, the Hong Kong Stock Exchange suspended trading in Carrian Group shares.

For BMF, this meant that they were unable to collect back on the loans they gave to Carrian Group… an amount that we’re saving for the next point below. Under normal circumstances this could have been chalked down as an unfortunate business decision, but it turns out that…

BMF was pinjam-ing money without proper approval (!!)

Even before the Carrian group was taken off the Hong Kong Stock Exchange, BBMB officials started suspecting that something fishy was happening at BMF and quietly sent an auditor over to Hong Kong for an internal investigation in December 1982. This man was Jalil Ibrahim, a senior BBMB auditor who was known for being too good at his job.

As it was later revealed, BMF wasn’t just lending money to Carrian Group – they were basically bankrolling the company with loans amounting to RM2.5 billion! Worse, BMF weren’t following proper banking protocols by overlooking dodgy paperwork from Carrian Group and approving the loans without proper collateral:

“To facilitate the acquisition of Gammon House, [BMF] alone held out a staggering US$292 million credit to a new ‘two-dollar’ company solely controlled by the Carrian chairman.” – Quoted from the Independent Commission Against Corruption (ICAC) Hong Kong case files.

In case you aren’t familiar with the term ‘two-dollar company‘, it refers to companies that are set up with a minimum capital of 2 dollars. This means that if the company cannot pay its debts, the people it owes money to can only collect… 2 dollars.

At the same time this was all happening, Bank Negara also started its own investigation into the BMF. This was kept on the down-low for a few months until…

A body was found in a banana plantation in July 1983

On July 19th 1983, a body was found in a banana plantation in New Territory, Hong Kong; with a bathrobe cord around the neck. There was no wallet or identification on the body, but investigators found a 10 sen coin that fell between the lining of the pants worn by the deceased. It was BBMB auditor Jalil Ibrahim.

You can watch the documentary above for a fuller story, but the gist of it is that on the day before his body was found, Jalil Ibrahim left the office carrying about HK$36,000 in cash and informing his assistant that he had an appointment at a hotel with a client. It was common practice back in the day for senior bank executives to exchange currencies by hand for important clients.

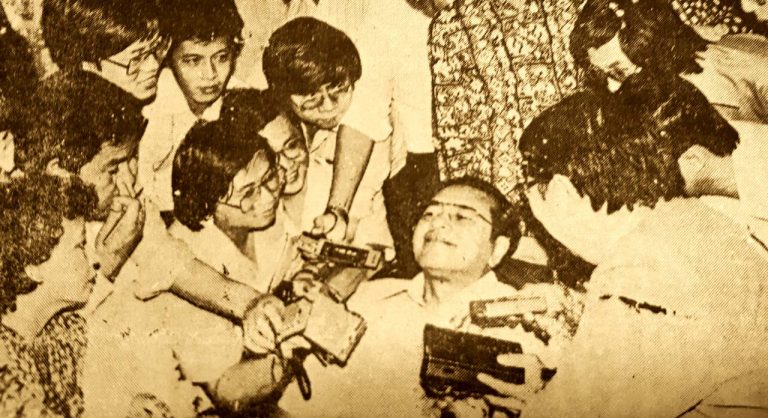

Police later identified the mystery client as Mak Foon Than, a Malaysian businessman who regularly travelled to Hong Kong. A short chase and a jump off the third floor of an apartment later, Mak was in the hospital under police custody. However, Mak claimed that he didn’t kill Jalil, only helping to dispose of the body – the real killer was a South Korean man named ‘Mr. Shin’. But when ‘Mr. Shin’ was arrested in Korea, he managed to prove that he wasn’t in Hong Kong at the time.

While Mak was eventually found guilty of the murder, the actual motive behind Jalil Ibrahim’s murder has remained a controversy to this day. Many have linked his murder to the Carrian Group because, as the person in charge of the audit, Jalil was also the only person who could authorize loans. He rejected a US$4 million loan that the Carrian Group desperately needed to keep afloat shortly before his death.

By this point, Jalil Ibrahim’s murder had attracted the attention of news reporters all over the world, and Malaysia was in the spotlight of a major financial scandal. And also by this time, many people started asking the Malaysian government for answers…

But the Gomen wasn’t very cooperative

As mentioned, the Carrian Group was a ‘two-dollar company,’ so when the company went bust in 1983, the unpaid loans had to be absorbed by BBMB. This took a huge toll on the bank to the point that Permodalan Nasional Berhad (which owned 70% of BBMB shares) had to inject a further RM600 million to keep it afloat. However, there were many unhappy people, because most of the money lost were actually public funds – the additional RM600 million from PNB, for example, was actually money from Amanah Saham Nasional (which came from Malay investors).

Many parties including the Opposition and trade groups asked for a Royal Commission of Inquiry to investigate the scandal, which was denied by the Malaysian government on grounds that the BMF was established in Hong Kong so it was out of Malaysian jurisdiction. Instead, the government established a 3-man Committee of Enquiry led by Auditor-General Ahmad Noordin. The issue was also not discussed in Parliament because Tengku Razaleigh – now Finance Minister – invoked banking secrecy laws to prevent disclosing any details of the case.

But when the Committee finally released their report in 1986, Mahathir refused to release it to the public because he didn’t want the government to get sued by the people named in the report. Alongside public outcry, Auditor-General Ahmad Noordin himself asked the government to release the report, and was apparently told by Mahathir:

“If damage is done to the credibility or credit-worthiness of BBMB … the bank will be fully justified in suing you for damages” – Dr. Mahathir as quoted by Far Eastern Economic Review via Yik Koon Teh.

Ahmad Noordin and Chooi Mun Sou (another member of the Commission) agreed to take responsibility and the government made 2,000 copies of the report available for sale at RM250 each. Most of these copies were bought by BBMB. The government also released a White Paper report a few months later that was said to be “heavily whitewashed“.

Among the things that the Committee discovered were that:

- BMF continued lending money to Carrian Group even after they announced they were unable to repay loans.

- Half of the RM1 billion funds allocated to BMF was unaccountable for.

- BMF’s overseas lending limits were increased to allow more funds to be channeled to the Hong Kong branch even after other banks stoped lending to Carrian Group.

And even then, the question remained…

Who was responsible for losing RM2.5 billion of Malaysian taxpayer money?

Just to add to the mystery, there are two schools of thought on who was responsible for the Bank Bumi fiasco. Officially, the pointy finger of guilt fell upon the five people in charge of the Hong Kong BMF branch at the time:

- Tan Sri Lorrain Esme Osman – Director of BBMB and BMF

- Datuk Hashim Shamsuddin – Second director of BBMB and BMF

- Tan Sri Kamarul Ariffin – Group Chairman of BBMB

- Dr. Rais Saniman – Senior GM of BBMB’s International Banking Division and alternate director of BMF

- Ibrahim Jaafar – GM of BMF and Chief representative of BBMB

All five were said to have close links to Carrion Group chairman George Tan, and had (as Dr. Mahathir himself revealed) received a consultation fee of HK$3.3 million from BMF on top of their salaries and allowances. You can read about their individual fates in SOSCILI’s original writeup here, but we’ll use the space to talk about the other party some people believed were responsible for the BMF scandal – parties that were placed a little higher up the food chain.

“Testimony from the murdered BMF official’s trial in Hong Kong links the defendant to Razaleigh and other unnamed cabinet officials.” – CIA intelligence document.

The unofficial fingers of guilt pointed to Tengku Razaleigh and several unnamed ministers. An activist group believing that Lorrain Osman was a scapegoat reportedly found evidence that George Tan was acting as a private broker and financier for Tengku Razaleigh, along with giving him shares that were expected to be worth HK$50 million. Also, while in questioning, Mak Foon Than claimed that he worked for Tengku Razaleigh and was in Hong Kong collecting money on his behalf; which Tengku Razaleigh denied. Mak later denied making this statement during his trial, and a 24-page transcript of his interrogation went missing:

“The 24-page statement made by Mak in which he implicated George Tan and I think even other people in Malaysia had mysteriously disappeared, and to this day nobody knows what happened to that statement.” – Winsome Lane, Court reporter, in The Banker Who Knew Too Much

However, the one person who (probably) was NOT directly involved in the shady dealings at BMF at all was (dun dun dun)… Dr. Mahathir.

This was mentioned in the CIA document as well as by Lorrain Osman:

“Thus far no direct links have been established between Mahathir and the corruption at BMF” – CIA intelligence document.

“I have no evidence of Mahathir’s involvement. I know for a fact that the executive directors of the bank who were overseeing the running of BMF were doing things that I knew nothing about. …” – Lorrain Osman, as quoted by The Malaysian Bar via The Sun.

Instead, the CIA thinks that Mahathir was trying to contain the situation because of the political implications due to George Tan’s alleged ties with high ranking UMNO officials. On top of that the scandal would have also brought the now-controversial NEP into question since the scandal involved money that was supposed to help out Bumiputras was instead used to bankroll dodgy Chinese businesses.

The BMF Scandal came with a very high cost…

… for both the country and the people involved.

In 1984, the government used Petronas to buy up 90% of BBMB shares for RM933 million along with absorbing RM1.2 billion of the bad loans. Today, Bank Bumiputra is gone – bought over by CIMB in 2005, in what was referred to as “putting together a good operation (CIMB) with one that is poorly managed“.

But aside from the monetary cost, several lives were also affected by the scandal – Lorrain Osman spent the rest of his life in the UK maintaining that he was innocent and that he regretted not leaving BMF and starting his own bank. He died in 2011.

But the highest cost was probably paid by Jalil Ibrahim and his next-of-kin. While we still don’t know the real story behind his death, police found some of his personal notes which hinted that he might have been part of something that went far beyond his control… and he wanted out of it:

“The bank has been used and commissioned to make money for political ends. … I have tried to tell some truth, what good it will do? More likely I will be without employment, but that may be preferable. … The directors may have been lazy, but the politicians have been corrupt.

So much for the people, the race and the country. I am just a small part of the deception. I want no more to lie and betray the bank or my family”. – Jalil Ibrahim’s personal notes, quoted by Yik Koon Teh via the South China Morning Post.

- 8.3KShares

- Facebook7.2K

- Twitter121

- LinkedIn62

- Email165

- WhatsApp728