In the 1800s, Johor and Singapore implemented the… Kongkek System?

- 1.1KShares

- Facebook997

- Twitter13

- LinkedIn13

- Email17

- WhatsApp50

[This article is based on one written by SOSCILI. To read the article in BM, click here!]

Here’s a quick pop quiz: what are the symbols of Johor?

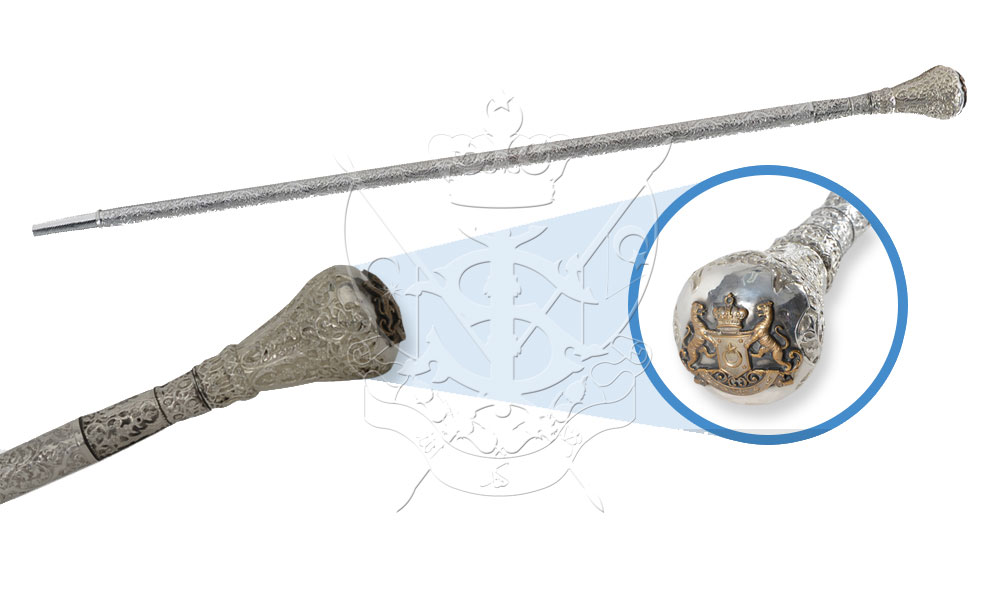

Well, the most obvious one would be the tiger, but if you look at some streetlights in Johor or stuff related to Johor royalty, like their castle’s decor or the royal regalia, you might notice that some of them have a recurring leafy motif.

Chances are, what you’ve found would be depictions of either the pepper plant, the gambier plant, or a combination of both. As for why these two plants specifically… no, it’s probably not because Johor people just really like spicy food. Pepper and gambier played a pretty important part in Johor’s history, and it probably wouldn’t be an exaggeration to say that modern Johor started out because of it.

The story began back in the 19th century when…

Johor experienced a massive influx of Chinese planters in the 1840s

The story began some time before Temenggung Daeng Ibrahim, the ancestor of Johor’s current dynasty, achieved real sovereignty there in 1855. Even before this story began, pepper and gambier were all the rage in Singapore’s plantation fields and the surrounding Riau islands. Pepper was spicy, and gambier was used in the leather and dyeing industry. So there was a huge demand for them.

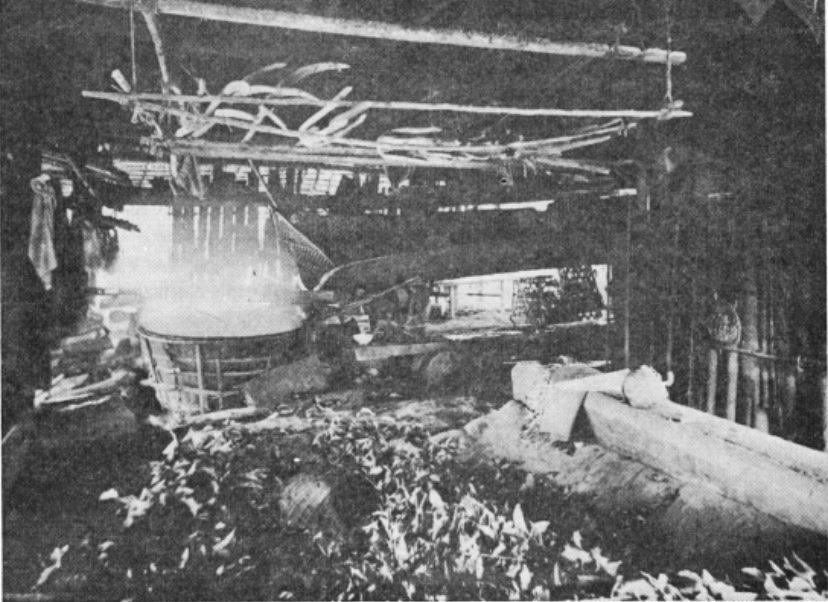

These two plants were often planted together, as the waste from processing gambier was used as fertilizer for the pepper plants. However, despite the beautiful brown color that gambier gave to leather and fabrics, it sucked the land dry of nutrients, so generally you can’t have a gambier plantation in one place for too long. This was kind of a problem for Singapore’s gambier industry, because by around 1840 most of the tiny island’s plantations can’t grow gambier anymore.

Many, if not all, of these gambier and pepper planters in Singapore belonged to the Ngee Heng secret society (kongsi), or more popularly known in our history books as the Ghee Hin. The British in Singapore didn’t really like all these kongsi-kongsi stuff, and with land administration problems there, it’s safe to say that the planters were looking for a different place by then.

Cut back to Temenggung Daeng, who around that time wanted to clear Johor of forests and develop it into something. We dunno which came first: the Temenggong inviting all these Singaporean planters to set up plantations in Johor, or a Ghee Hin leader calling for the planters in Singapore to move over to Johor. Regardless of which came first, the planters moved to Johor in droves sometime in the 1840s, and so begins our story.

Allright, Cilisos, you might say by this point. What does all this have to do with Kongkek, which I came here for? Keep your shirt on, we’re getting to that.

The planters followed a system of kangchus and river documents

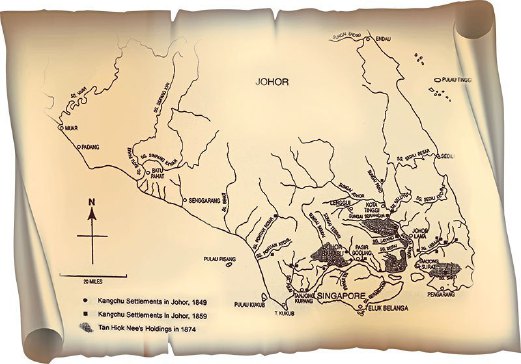

Now, there’s another term from our history books. The kangchu system might have been practiced elsewhere, but quite a number of documents that reference it were found in Johor, suggesting that Johor was the place where it was used the most. The term sounded pretty intimidating in Form 5, but you can think of a ‘kangchu’ as a person who starts plantations along Johor’s rivers back in the day. In Teochew, the term roughly translates to ‘master of the river‘.

Back when Temenggong Daeng invited the planters to set up their plantations in Johor, most places were filled with thick jungle, including places where plantations were ideal (by the rivers). So the Johor government then worked out a system where people would apply to clear a certain spot for their pepper and gambier plantations.

The government would then lease the land to successful applicants, and the deal would be sealed by the issuance of something called a ‘surat sungai‘ (river document). People who managed to get these river documents were called kangchus, and they act as a general manager of sorts for the areas leased to them, which were known as kangkar.

Establishing a kangkar was a costly business venture, often funded by several stakeholders who can come from as far away as Malacca. However, the returns seemed to be very lucrative. By the end of the 1880s, Johor emerged as the world’s top producer of gambier and black pepper, and in the years following that, the prices of the commodities experienced a massive jump. Between the late 1860s and the early 1880s, the price of black pepper jumped from about $6 to $15 per picul (1 picul = 60.48 kg), and gambier from about $2 to $7 per picul.

But that’s just commodity-wise. We’ve written about revenue farming in another article, but in simple terms, kangchus also typically held government-sanctioned monopolies and concessions on their kangkar as well. These businesses, which included the sales of opium, pork, and alcohol, as well as gambling and pawn-broking, were highly profitable and made kangchus filthy rich. Gambling in Johor’s kangkars were particularly popular, as it was banned in Singapore.

As gambier, pepper, and the kangchu system progressed…

The Kongkek society used the Kongkek system to control the price of exports

Finding information about the Kongkek had been challenging, because there were a lot of distractions once you Google ‘kongkek Johor’. Based on what we’ve found, though, the term seemed to differ based on whether you’re talking about the Johor Kongkek or the Singapore Kongkek.

Remember how we said that several stakeholders may fund the opening of a kangkar? These stakeholders were essentially the pepper and gambier towkays, and in 1865 they assembled into the Gambier and Pepper Society of Singapore, also known simply as the Kongkek. Together with the revenue farmers, the Kongkek controlled the production of gambier and pepper in Johor, and they regulated the associated payments to the Johor government, the planters, and themselves.

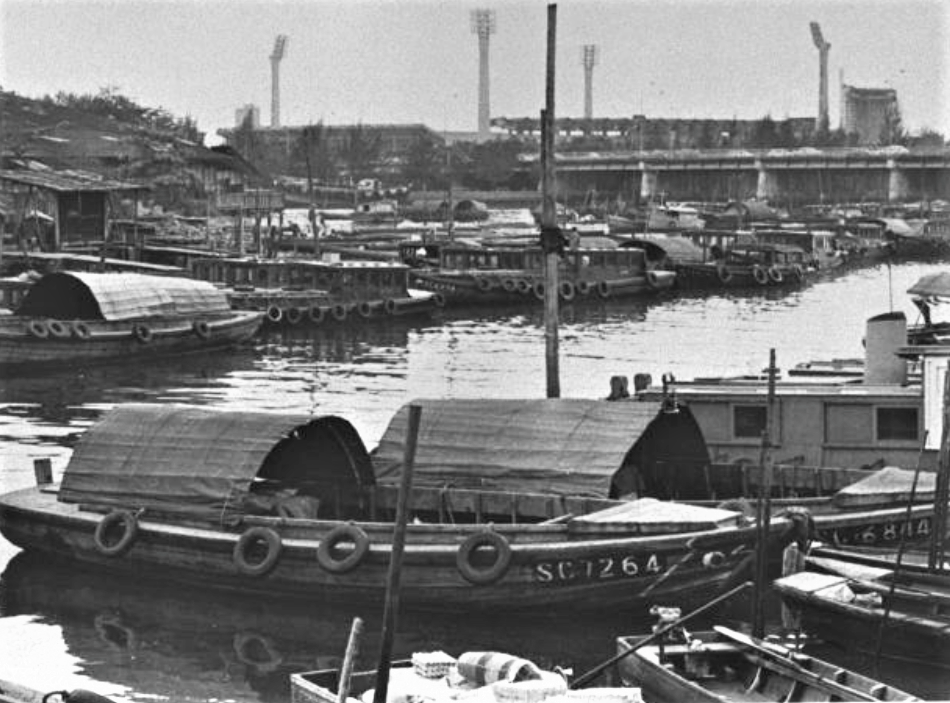

Back then, pepper and gambier from Johor travelled by boats to Singapore where they would later be exported, and without the Kongkek’s assent or knowledge, the boats cannot be landed. If such a boat landed anyway, or if it arrived without a proper note from the kangchu where it came from, the boat would be seized by the Kongkek. Such was their influence on the industry.

On the Johor side, the Kongkek seemed to have a different role. It was said that the towkays provided the starting capital to the kangchus on the condition that the kangchus sell their produce back to the towkays at a fixed price that’s lower than the market value. To ensure that their rights were protected, the towkays appealed to the Johor government, and in 1884 an association called the Kongsoh was born.

This association employed a semi-governmental surveillance system called the Kongkek, whose officers were appointed by the government with the towkays’ assent. The officers and staff involved in this Kongkek were also known as Kongkeks, and their task was to examine every boat carrying pepper and gambier from the kangchus to ensure that the commodities reach the correct towkays.

They also had the power to seize earmarked produce that was sold to other merchants. Other tasks of the Kongkek include quality control and even settling disputes among bordering kangkars. At its height, Kongkek branches were established in most major towns in Johor.

However, it would seem that the Kongkeks and kangchus didn’t last very long…

With new crops and a new government, the kangchu system disappeared from Johor

As with many fads that come and go, gambier and pepper soon lost their popularity with the planters. By the end of the 19th century, the planters had experimented with other agricultural crops like coffee, tapioca, and tea, but due to fluctuating prices, these crops didn’t stay for too long. Pineapple and rubber, on the other hand, became the next top crop in Johor owing to the higher, more stable profits they brought.

Gambier and pepper planting was no longer profitable by then, and gambier’s function in tanning and dyeing industries at that time was being replaced by synthetic chemicals instead. The number of gambier and pepper plantations dropped, and planters turned to rubber plantations. The decline may also have something to do with the colonial government surpressing traditional methods of farming gambier, which depleted the soil of nutrients and depleted the forests of firewood.

Anyway, as gambier and pepper plantations faded from Johor’s map, so did the Kongkek and the kangchu system, although maybe there was another reason for the kangchus’ disappearance. Remember how earlier we mentioned something about the Ngee Heng kongsi being involved in the whole planting thing? There was a complex relationship between the kongsi and the Johor government, but they generally liked each other.

However, the British didn’t like the whole kongsi situation. After the British set foot in Johor, they attributed the high crime rate in the state’s Chinese settlements to this kongsi, which was kind of a duh moment as a majority of the Chinese planters in Johor were under the kongsi. Anyhow, they finally managed to pass an enactment that dissoluted the Ngee Heng kongsi in 1916, and the kangchu system got abolished the following year.

While you might be hard pressed to find actual pepper or gambier plants in Johor today, it can’t be denied that the plants played a significant part in modern Johor’s history. Along with the kangchu system, these plants were arguably the spark that started off Johor’s development into what it is today. So the next time you visit Johor and see pepper- or gambier-themed decorations, you’ll know what they represent, and why they’re there.

- 1.1KShares

- Facebook997

- Twitter13

- LinkedIn13

- Email17

- WhatsApp50