We found Malay political comics from the 1930’s. They were unbelievably savage

- 1.5KShares

- Facebook1.4K

- Twitter10

- LinkedIn7

- Email11

- WhatsApp57

If you were around a few years back, you might have seen cartoons like this floating around:

This cartoon was the work of Zunar, and it’s generally known as a political cartoon, a subset of editorial cartoons. They’re pretty easy to recognize, often using indirect symbolism and caricatures, usually in a single panel, and carrying some current political or social message. The aim of such cartoons is usually to get people to think about current events.

The hot topic for the past decade had been corruption and the government’s shortcomings, and the implied message for the cartoon above wasn’t that hard to guess if you were aware of current events: the rakyat being taxed more to support corruption by the people in power. It’s pretty much spelled out, after all.

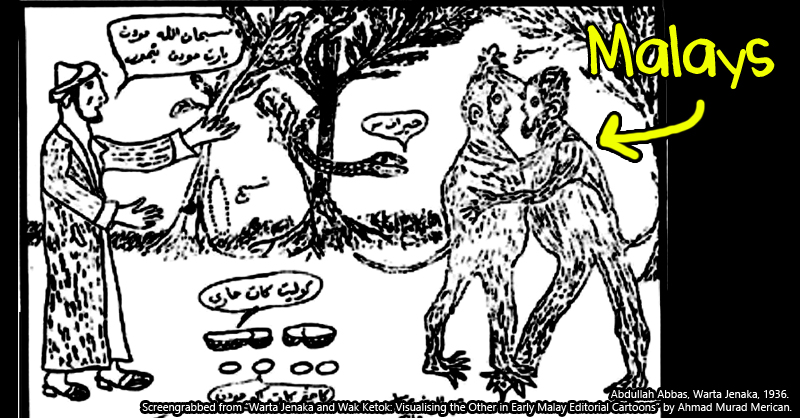

But can you guess the message from this editorial cartoon… from 1936 Malaya?

Some of you might guess that since the British was colonizing Malaya at that time, this was a critique on how out of place British people must be in the jungles of Malaya, strutting about in their European clothes while the Malayans stare with much curiosity. Not a bad guess, considering the caption. However, an interesting thing to note about editorial cartoons in Malaya pre-Merdeka is that…

They seem to focus on the identity of Malays

Editorial cartoons first appeared in Malaya in the 1930s, a time when Malay newspapers – Warta Jenaka, Warta Ahad, and Utusan Zaman, to name the major ones – started to show interest in racial consciousness and the future of the Malays. Surrounded by British colonizers, the ‘other’ Malays (which include Malays with Arab and Indian heritage) as well as newly brought in Chinese and Indian immigrants, the Malays then seem to think about their identity and place in Malaya.

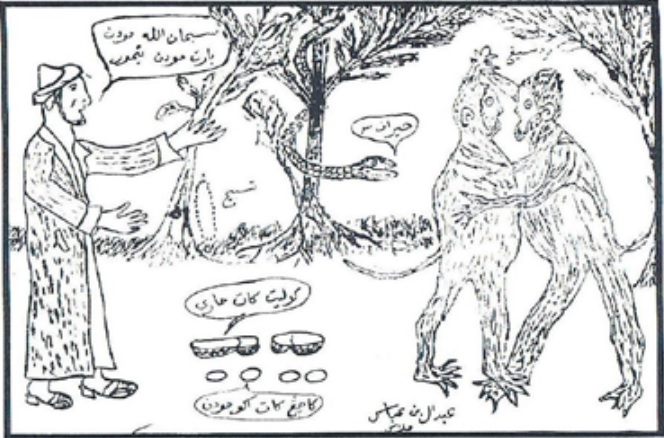

So while editorial cartoons then cover a wide range of topics and events, this became a common theme in the cartoons published pre-independence. In the cartoon above, the apes wearing European clothes were actually meant to reference Malays who ‘aped’ Westerners (geddit?) by adopting their mannerisms and clothing. Modernization though Western influences were seen with unease, being blamed for the corruption of thought and behavior particularly among urban Malays, and several other cartoons echo this sentiment. For example, here’s one that’s also from 1936:

Here again, Malays who glorify Western cultures were depicted as two monkeys dancing together (apparently a Western activity), while pious man in an Arabic garb exclaims “Subhanallah! Moden Barat, moden Timur” (Glory be to God! Modern West, modern East), dropping his rosary at the sight. A nearby snake comments ‘hairan’ (strange), while peanuts and their shells lay nearby, alluding to the Malay proverb ‘kacang lupakan kulit‘ which refers to people who forgot their origins. The shells say ‘kulit kata mari‘ (the shells say come) while the peanuts say ‘kacang kata aku moden‘ (peanuts say “I’m modern”).

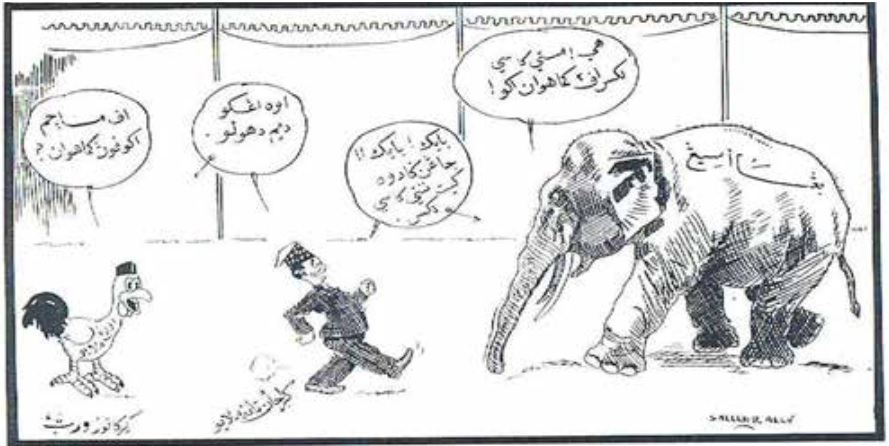

As for the Malays’ position in Malaya, the British economic policy of bringing in Chinese and Indian labor to exploit Malaya’s resources in the early 1900s had left the Malays feeling sidelined. The policy seemed to only benefit the aristocrats who got compensated, with the Malay peasant gaining nothing from this. The sentiment was pictured in this 1938 cartoon:

The elephant was labelled as ‘bangsa asing‘ (foreign races), and it demands for the Malayan government (represented by the man) to give it what it wants ASAP. The man essentially replies ‘Yes! Yes! No need to worry, we’ll give it to you promptly’. The Malays, represented by the chicken wearing a songkok, asks the man what of their needs? To which the man replies “Oh you settle down first.”

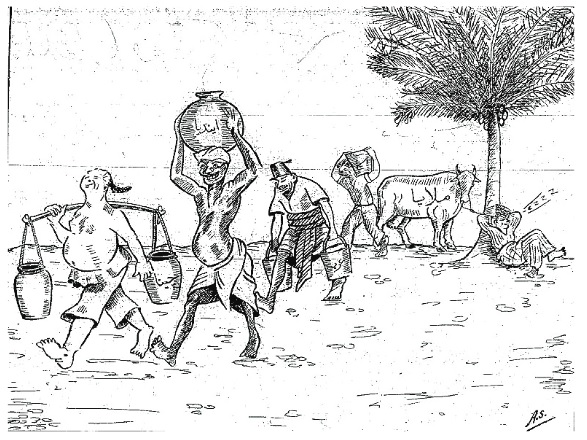

Interestingly, some of the cartoons had a different take on this matter by pointing out that the Malays were partly to blame for the situation, as they didn’t expend any effort in utilizing the resources that they have. In this cartoon from 1939, a Malay was depicted sleeping under a tree with his cow (representing Malaya) tied up beside him. Caricatures of other races (from left: Chinese, Indian, Arab, and others) were seen milking his cow while he slept.

Yes, that’s an Arab guy wearing the tarbus (fez). Arabs actually had some major appearances in these early comics, as…

The Malays had to compete with Arabs and ‘other’ Malays as well

Besides the British, the Chinese, and Indians, the Malays had also sought to find their identity and place while coexisting with Arab and Jawi Peranakans, and this struggle was most prominently seen through a cartoon character named Wak Ketok, a chameleon-like character identifiable by his trademark long nose.

Wak Ketok cartoons were published in the Utusan Zaman, the Sunday paper companion for Utusan Melayu whose editor was famed journalist Abdul Rahim Kajai. Rahim Kajai had been in the forefront of a concept called Takrif Melayu (a definition of Malay), a complicated ideology that essentially sought to establish what it means to be Malay and use it as a vehicle to advance and solidify the Malays’ place in Malaya.

Wak Ketok was born at a time when Arab and Jawi Peranakans dominated Singapore’s Malay community through their higher status, and Utusan, being the first newspaper wholly owned and operated by ‘Malay’ Malays, fought to change that. A significant number of Wak Ketok’s cartoons were critical of these Peranakans, who were termed as ‘foreigners in disguise‘, and the Malay-Arabs were a frequent target.

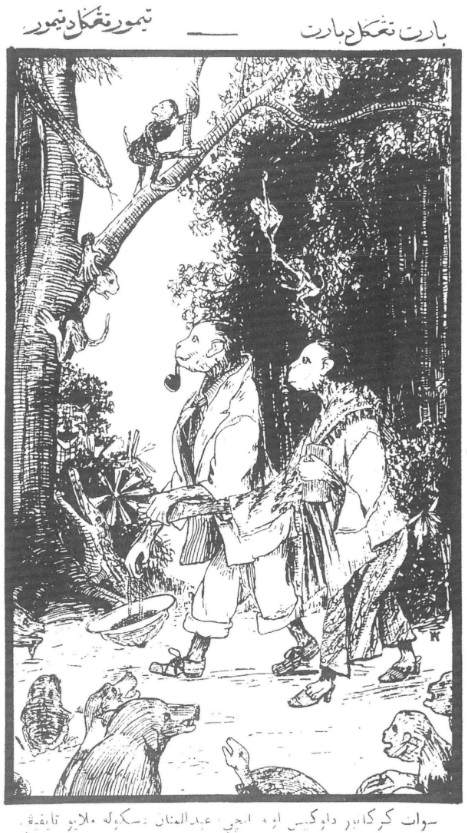

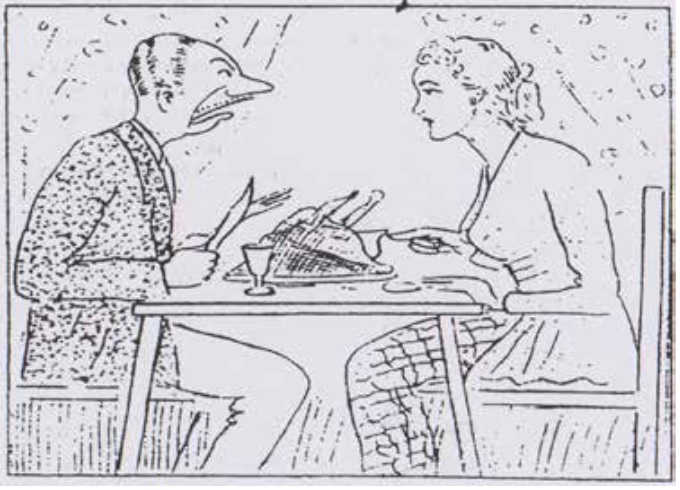

They were depicted as obsessed with modernity brought on by the West, overly presumptuous of them leading the Malay community, extravagant, pretentious, and morally corrupt despite an outward appearance of piousness. When embodying the character of a Malay-Arab, Wak Ketok would often behave in a non-Islamic fashion – drinking, gambling, and dancing wildly – or simply just acting in a way removed from the common Malay, like in this cartoon.

Playing the part of a pretentious Malay-Arab, Wak Ketok was depicted using cutlery and fine dining whilst wearing a suit, all activities that were alien to the common Malays then. The title of the cartoon also hinted at another pretentious trait: some Arab and Jawi Peranakans were known to add a ‘Yang Mulia‘ in front of their names. In the same vein, Wak Ketok also criticized Malays for their deference and fascination towards the Arabs, showing a lack of Malay pride and support for their fellow Malays.

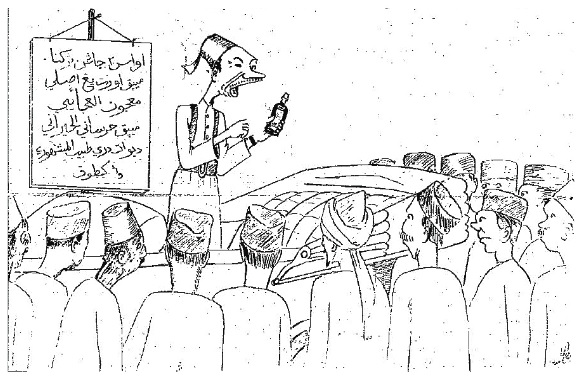

In this cartoon, Wak Ketok dresses up as an Arab, selling medicine while standing inside his luxury car, with a placard with Arabic-sounding Malay jargon behind him: “Awas2 jangan terkena. Minyak urut yang asli, Makjun al-Ajaibi, Minyak Harussani al-Hairani, dibuat dari tabib al-Mahsyuri Wak Ketok“. The Malay crowd gathering around him implies the fascination of Malays with Arabic elements – the clothing and the Arabic jargon – despite the product obviously being a scam.

There’s more to Wak Ketok’s story than we can fit in this article, so if you’re interested to know more, you can check out this journal (might need to use something to access though). But it’s kinda interesting to note that…

Editorial comics can offer a new perspective on history

It’s sometimes hard to take cartoons seriously, but that’s actually one of their strengths: it pierces through people’s guards and enables a more direct and pointed critique. While we may not learn much about the cold hard facts of historical events from them, editorial cartoons can often offer an honest view of what people from the past really think of those events.

In the case of Malaya’s early editorial comics, we learned that Malays actually did have an opinion on the mass immigration of Chinese and Indian laborers, that some of them are aware of how that only benefits the aristocrats, that white worshipping was a thing even back then, and that using Arabic gibberish to sell things to Malays had been around for a while, among other things.

It’s kind of interesting to know that some things haven’t changed after almost a century, and that got us wondering: would Malaysians 100 years from now say the same thing after seeing our current editorial cartoons?

- 1.5KShares

- Facebook1.4K

- Twitter10

- LinkedIn7

- Email11

- WhatsApp57