Msian govt may control drug prices as private hospitals allegedly sell meds for 900% MORE

- 2.2KShares

- Facebook2.1K

- Twitter9

- LinkedIn10

- Email8

- WhatsApp35

It’s no secret that going to a private clinic or hospital can be pretty darn expensive, and a bulk of that hefty bill can come from pricey medicines. With a survey finding that 87% of patients in Malaysia depend on private healthcare for their medicines, the price is quite a problem.

The government has been trying to do something about it, and in April this year they’ve announced the decision to control the price of medicines in private healthcare. However, it wasn’t as easy as the Cabinet agreeing to it: as of the time of writing, they’re still holding conversations with the relevant stakeholders.

Today, we’ll be taking a look at why it may be hard to make private healthcare (and their medicine) cheaper, but first, it’s important to know that…

There’s practically nothing stopping private hospitals from charging what they want for medicines

[PSA: We may use the term ‘medicine’ and ‘drug’ interchangeably for this article, as their meanings overlap. Technically medicines bring about a positive effect, while drugs can bring both good and bad effects.]

Private and public healthcare in Malaysia are generally two separate systems mostly independent from each other. Public healthcare is funded by the national budget, while private healthcare gets their money from patients (out of pocket payments, OOP), private health insurance and employer benefit schemes. So one is more dependent on profits than the other.

With that established, let’s look how they set their medicine prices. The public healthcare system controls and procures medicines at lower prices through several strategies. One of them is through a Drug Formulary, which is a sort of list of reasonably priced drugs as reviewed by panels for use in public health facilities.

Medicines are also bought in bulk through Concession Companies, national tenders and local purchases, with prices set through something called the International Referencing Pricing (IRP), where drug prices outside the country are used as reference. There are also assessments and evaluations on drugs to ensure that they’re cost-effective, and a policy that favors generic medicine (which we’ll explain more later). Note that this is from a journal, and may not reflect alleged actual practices.

While the government does have a law governing private healthcare in Malaysia, it only sets the price for general practitioner (GP) fees and specialist fees, with no mention of how private healthcare should set prices for their drugs, practically leaving it up to their conscience the free market. However, a study published last year showed that the free market did little to control drug prices.

In an annual survey spanning five years, it was found that private healthcare facilities (hospitals and clinics) marked up the retail price of their medicines (price at which they sell) by somewhere between 24% to an eye-watering 402% from their procurement price (price at which they bought). Lim Chee Han, senior analyst at the Penang Institute, claimed that in some extreme cases in private hospitals, the mark up may get as high as 900%.

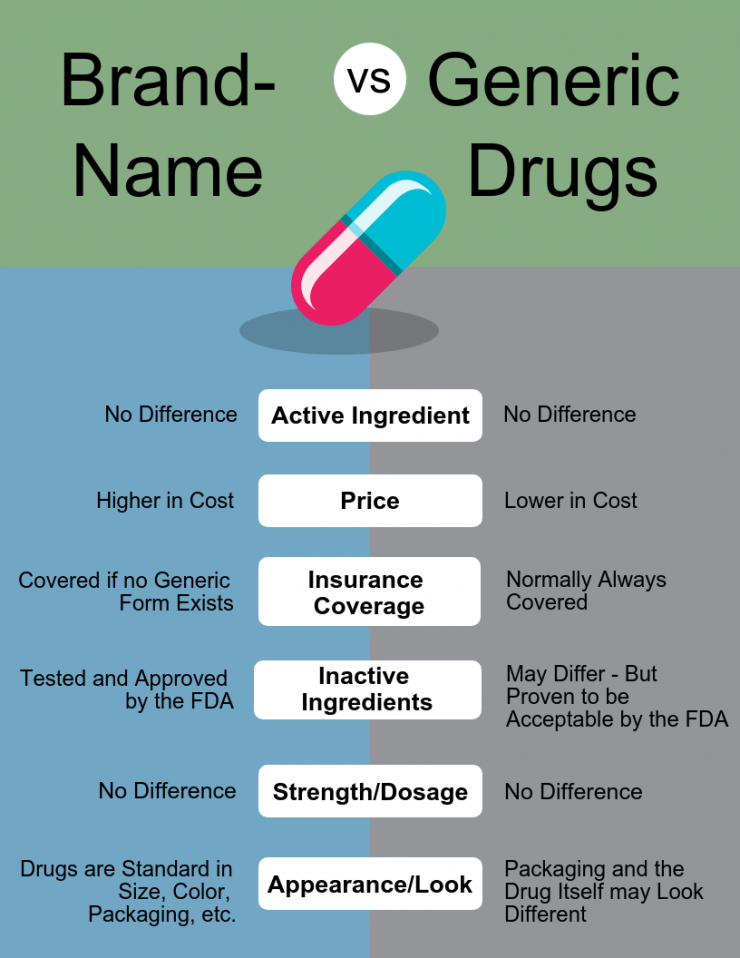

Interestingly, the price of generic medicines got marked up by a lot more than innovator medicines. Put simply,

- Innovator medicines are ‘new’ medicines protected by a patent, so no one can copy and sell them. This gives the makers a monopoly, making it more expensive.

- Generic medicines are innovator medicines whose patents have expired, enabling other companies to copy and sell them. The competition between these companies and the R&D and testing costs out of the picture makes them a lot cheaper.

The low price of generic drugs makes it possible for private hospitals to increase their retail prices by a lot, but still make them seem like a cheaper option compared to innovator medicines.

It was also found that while private pharmacies also mark up their drug prices, they are still lower than private hospitals to attract customers and remain competitive. Private hospitals often have no need for that, as they often don’t have to disclose their medicine prices to patients, instead charging it directly to insurance companies. This puts the difference in prices between private hospitals and pharmacies to be around 20-150%, prompting a trend where companies deal directly with pharmacies to save money in terms of staff medical benefits.

Based on these alone, it would seem that the government needs to do something about it. However, it’s not as easy as just making up new laws.

It has been over a year since the plans to control drug prices was first announced

Sometime in July 2018, the government announced that they’re planning a mechanism to control the price of medicine, although at that time they didn’t say for which sector. In November, Health Ministry Datuk Seri Dr Dzulkefly revealed a little more about the plan, saying that the ministry will use the price control mechanism to determine the ceiling price of medicines for consumers at all dispensaries. Simply speaking, they will set a maximum price that will apply wherever you get your medicines from.

High medicine prices had been a global issue for some time already, and according to the World Health Organization (WHO), while the best way to ensure low medicine prices is through competition, governments can try setting up price controls if proper organization of the market and anti-monopoly laws don’t work.

So in April this year, the Cabinet approved the decision to impose drug price controls. The ceiling price will be based on external reference pricing (ERP), where the government will look outside the country for the average of the three lowest prices of a certain drug. This ceiling price will be imposed at not only at the retail level (clinics, hospitals and pharmacies) but at the wholesale level as well.

“We will be using the highest ceiling price determinant. You cannot charge more than that. I know the private sector may not be very comfortable with this, but we have to take a solution that will fit all. We cannot be selective. It must be one that cuts across the board,” – Datuk Seri Dr Dzulkefly, as reported by FMT.

To do that, new regulations will be gazetted under the Price Control and Anti-Profiteering Act 2011. On the enforcement side, the Health Ministry will collaborate with the Domestic Trade and Consumer Affairs Ministry, which will appoint officers from the Health Ministry to be price assistant officers.

However, no gazetting will be done until the Health Ministry until further discussions are completed with the relevant stakeholders, and as of the time of writing, it appears that the discussions are still ongoing. Still, one might wonder…

Will controlling the price of drugs really help the rakyat?

Since the announcement in May, several quarters have talked about how it might change things, and an often quoted case is India’s healthcare system, which had deployed price controls for some essential drugs since the 1990s. Nadiah Wan, CEO of Thompson Hospital in Kota Damansara, have said that the price controls on implants in India have caused many multinational pharmaceutical companies to leave the market, and the same could happen to Malaysia.

“So I can imagine that perhaps some of the European companies may find it no longer worth it to bring their products in, and we may lose access to certain medications,” – Nadiah Wan, as quoted on Code Blue.

Besides the risk of losing out on certain innovator medicines, there might also be a possibility of some rural people losing out on medication. Amir Ullah Khan, a professor at the MCR HRDI Institute of India, have said that that’s what happened there. Since price controls put a limit on how much you can charge on a certain drug, it limits the potential profits of people along the supply chain, including the distributors. With poor rural infrastructure in India, distributors found that sending drugs out to rural areas just aren’t worth the cost.

There is also the issue of overall billing. Medicine only makes up a part of hospital bills, and even then the price quoted for medicine often include other stuff like safeguards against wrong prescriptions, medication review, drug counseling, compliance monitoring, and titration of dosages as patient conditions change. It may also include other non-medicine related costs not chargable to the patients, like hand sanitizers and sterile bedsheets. As put by Nadiah Wan,

“Pharmacy items are one of the areas where the hospital generates enough of a margin to cover the cost of everything else.” – Nadiah Wan, as quoted on Code Blue.

Some general practitioners have also revealed that they depend on markups on drug prices to keep their businesses alive, as the consultation fees alone only bring in between RM10-35 per customer, as set by law. With that in mind, controlling the drug prices may not bring down the overall price of a private hospital bill, as they might just mark up something else.

“In a nutshell, this is the problem with India’s price controls. To recoup margins lost on controlled medicines, hospitals and pharmacies have increased charges in other areas and patients end up paying the same overall.” – Amir Ullah Khan, to FMT.

There are probably more potential ripples that may be caused by imposing a drug price control that we can’t fit in this short article, but you’ve probably got the idea that this might be a tricky policy to roll out. Complicated as it is…

Price controls alone may not solve the whole problem, but it’s a big step to take

If you think about it, there’s something sinister about medicines being so expensive, but at the other end of the spectrum we can’t expect the people who make and provide them to give them out for free either. Still, a 2005 study found that on average, a skilled public sector worker at the lowest rung on the pay ladder may have to spend 1.5 weeks of his salary to get treated for pneumonia at public health clinics, and 3.7 weeks of salary at a private pharmacy.

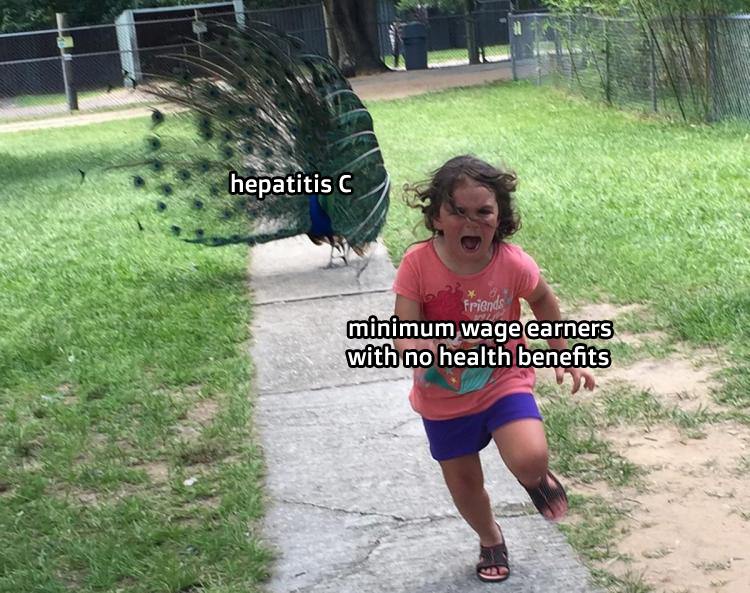

If having to spend to spend that much dough on for treatment isn’t sinister enough yet, consider the fact those calculations were from more than a decade ago, and were done based on a government worker subject to minimum wage. Today, of the 14.5 million workers who contribute to EPF, 30% earn less than RM1,000 a month. We didn’t find the figures for those whose employers didn’t care about EPF, medical benefits or minimum wages, but suffice to say that falling sick is not an option for them the way things are now.

This whole price control thing sounds complicated enough, but it’s just a small part of a jumbled mess of pieces that needs to be sorted out on the road to a more affordable healthcare system in Malaysia. It may not be as grand as other things the Malaysian government have done to address pricey medicines, like sponsoring an international proposal asking drug makers to reveal how they price their drugs or straight up seizing the means of production for a Hepatitis C drug, but it’s a step just as important, to ensure that those who need medicine in Malaysia can always have access to it.

- 2.2KShares

- Facebook2.1K

- Twitter9

- LinkedIn10

- Email8

- WhatsApp35