Murder on the KL Express: the train traveller who went on a killing spree in Malaya

- 1.6KShares

- Facebook1.5K

- Twitter7

- LinkedIn9

- Email13

- WhatsApp67

Anyone who’s read Agatha Christie’s famous detective novel ‘Murder On The Orient Express’ will have no doubt been enthralled by the page-turning exploits of Detective Hercule Poirot, who investigates a grisly murder on board the Orient Express.

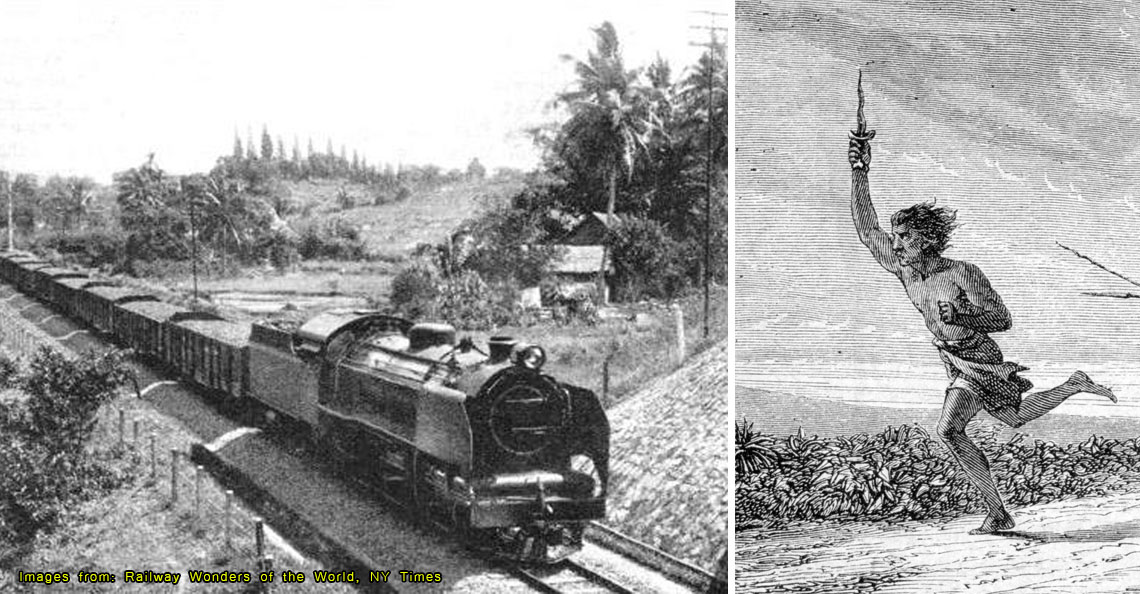

So imagine our captivation when we found out that such a story actually took place on our shores long ago, when a man ran amok and went on a killing spree on the KL-Singapore mail train, before proceeding to massacre residents of a nearby Kongsi house.

And the circumstances surrounding the killings are, well, bizarre to say the least. Read on…

Our story begins on a paddy farm in post-WWII Perak…

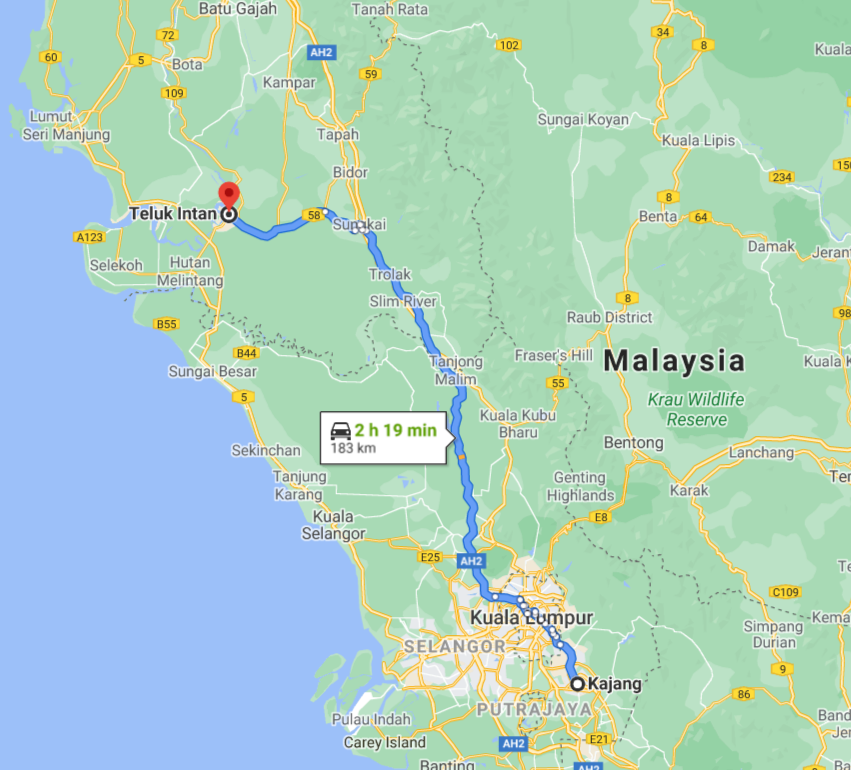

It was October 1947, and Mat Taram bin Saal, alias Utoh, was an Indonesian who plied his trade planting paddy at his farm in Teluk Anson, Perak. There was seemingly nothing out of the ordinary about Utoh, who hailed from Tunggal Island, near Sumatra. In fact, this whole episode started with good intentions: he simply wanted to visit his father in Sumatra.

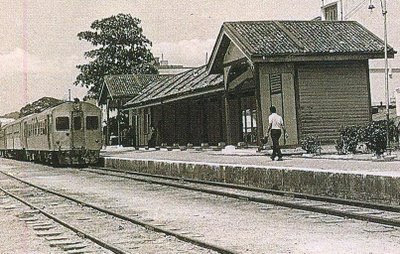

To gather funds for the trip, Utoh sold his house and land for 200 Straits Dollars. Following this, he took his wife and three children to Bidor by bus, and then to Singapore, from where he hoped to catch a ship to his hometown. However, when he inquired on the shipping charges, he found that he didn’t have enough money to pay for the trip. Dejected, he decided to return to Teluk Anson on the KL-Singapore mail train.

According to his wife, Utoh became severely depressed, and spent the next two nights without sleep, pacing about endlessly. And he was quiet throughout the train ride…

…until around 6:10 pm, when Utoh jumped out of his seat, pocket knife in hand

This sudden movement by Utoh surprised the Indian porter sitting next to him, who had also observed that he had been quiet up until that point. Utoh then attacked a group of British soldiers of the Royal Signals Unit who were on the same train. One of them, Sgt. Herbert Victor Marston put up a struggle, but was killed in the process, and the other three were left unconscious in a pool of their own blood.

Recounting the incident, the porter said:

“Just as the train passed Bangi station, he jumped up and rushed into the restaurant car and stabbed a soldier who was seated at a table eating with other soldiers. As he reached me, I fell down and I think my fall saved my life.” – Poachi, Indian porter (1947), as quoted from The Straits Times, 11th October 1947

Utoh went on a rampage, lunging at random people indiscriminately left and right. Cups and plates crashed to the floor, and the train interior was in utter chaos. Two more people (a Malay man named Mohamed Eusoff, and a Tamil man named Malimalia) ended up getting stabbed as well, before someone managed to pull the communication cord, which stopped the train. In the commotion, Utoh fell out of the train, possibly pushed, and disappeared into the nearby jungle. Meanwhile, the train proceeded to Kajang, where the injured were rushed to treatment.

An armed murderer was on the loose, so all off-duty policemen in Kajang were dispatched to search for him. Not far from the line, they found the body of a Chinese vagrant who had apparently been stabbed to death while cooking. They continued a further 3km, where they found a rubber collection hut at Sungai Tangkas Estate. There, they heard a single shout. They returned the call, but no one replied.

As they investigated the source of the sound, a boy came running towards them holding a cangkul, who told them what had happened to the Kongsi (Chinese organization) based there: a man had killed six people, including two elderly women and three young children. Another nine had been wounded, including four children, while the others were either hiding or too stunned to talk. It was reported that police found injured victims in every one of the hut’s thirteen rooms.

A woman widowed by the incident recounted her frightful experience:

“We never realized what was happening, I only heard someone screaming, and I caught my two children and ran from the house.” – Ng Tai (1947), as quoted from The Straits Times, 11th October 1947

While the boy from earlier, Liew Chuan, recalled that Utoh had ‘entered the hut from the back and rushed at everybody he saw’, moving at such a speed that ‘it all happened in a few minutes’. The police had only arrived about an hour after Utoh had left, and were later reinforced with backup units from KL. They cordoned off the rough triangle of Kan Kajang, Bangi and Semenyih, placing men at every half-mile and systematically combed the area within 3km of the Kongsi hut.

Driver J. Cormack (one of the British soldiers Utoh had stabbed on the train), Malimalai and one injured woman from the Kongsi later succumbed to their injuries, bringing the total death toll to 11. But Utoh was still at large and dangerous, and the police never found him. That is, until…

They eventually found Utoh… at home!

Amazingly, Utoh had carried on ON FOOT to Sabak Bernam, covering around 231km in 36 hours. He continued to his old Parit Six house, where he was questioned by one of the locals about what happened. According to Utoh, he had been pushed off his train after getting into a fight with a Chinese tea boy who had spilled tea on him, saying:

“I don’t know what happened after that but I walked back here.” – Utoh (1947), as quoted from The Straits Times, 13th October 1947

As for his wife and children, he simply said that he had ‘lost them’. The local suggested they seek police help, so they both went to the Sabak Bernam police station, where Utoh told them his story too. Upon hearing it, the Sub-Inspector recalled reading of an ‘amok’ case in a Malay newspaper, and so took him into custody. Later, Utoh’s wife and children arrived and identified him.

They had finally gotten their man.

The next day, he was formally charged with murder, but it wasn’t that simple

Although he appeared calm, it was clear that Utoh was in an unstable state of mind from the very start. At the beginning of the trial, he was reported to have said: ‘Kill me or set me free’.

Given the extraordinary circumstances of the case, it would be difficult for the murder charge to stick, as British law specifies that a person must be ‘of sound mind and discretion’, with the ‘intent to kill or cause grievous bodily harm’. That was the main point raised by the defense counsel Dr. H.Y. Teh, who argued that Utoh was ‘of an unsound mind as a result of which he ran amok’.

In fact, according to defense witness Dr. R.A. McNab, a medical officer from Tanjung Rambutan mental hospital:

“My impression was that he was a man of low intelligence with probably primitive ideas… who would give way to sudden impulses.” – Dr. R.A. McNab (1948), as quoted from The Straits Times, 5th May 1948

Indeed, Utoh appeared to have no memory of his misdeeds; upon hearing the explanation of his charge of the murder of a ‘white soldier named Marston’, he simply replied: “Who, me? No.”

Dr. McNab also noted that he had encountered such ‘amok’ cases before, saying that this condition appeared to be ‘peculiar to the Malay and Banjarese races’:

“It is generally due to some imaginary trouble or folly. The attack is characterized by sudden impulsive actions which would appear to be out of the individual’s control. The actions are generally manifested by violence and very often, unfortunately, it leads to the use of a lethal weapon. The attack in some cases lasts for some hours.” – Dr. McNab (1948), as quoted from The Straits Times, 5th May 1948

In conclusion, Dr. McNab said that Utoh’s insufficient funds to return to Sumatra may have brought about sufficient depression to trigger such an attack. Of course, we imagine the two sleepless nights couldn’t have helped either.

Because of this, Utoh was admitted to Tanjung Rambutan instead. At the end of the trial, the assessors (like a jury, but for capital punishment cases) found that although Utoh had committed killings, he could not be charged with murder as he was of ‘unsound mind’ when he committed them. Justice T.T. Russell agreed, and meted out the sentence.

Fortunately, the phenomenon of ‘amok’ is now better understood than it was back then

As Dr. McNab had said, ‘amok’ was indeed relatively common among the Malay community back then. In fact, the English phrase ‘running amok’ comes from the Malay word ‘mengamuk’, and the condition was first reported by Captain Cook, who observed it among Malay tribesmen in 1770. It usually involved an individual sufferer, who would go on a rampage and kill an average of 10 victims, before being put down by his fellow tribesmen. Think Hang Jebat after he found out about his BFF Hang Tuah’s ‘death’.

We could go into the issue of whether or not ‘amok’ qualifies as a ‘culture-bound syndrome’ (cos, y’know, the US kinda has ‘amok’ too, but with guns), but perhaps that’s an argument for another day. One thing to note is that it is generally seen as an indirect method of suicide caused by distress, which bears a striking resemblance to the mass shootings that occur in the US.

In any case, Utoh’s story simply further highlights the importance of mental health. Although thankfully ‘amok’ is virtually non-existent in Malaysia nowadays, rising suicide rates could mean that distress is being manifested in that form instead. So it’s never a bad idea to check up on your loved ones, especially during these trying times.

- 1.6KShares

- Facebook1.5K

- Twitter7

- LinkedIn9

- Email13

- WhatsApp67