Sarawak now allows the natives to get deeds for their land, but they… hate it? Here’s why.

- 1.1KShares

- Facebook1.0K

- Twitter8

- LinkedIn5

- Email13

- WhatsApp71

Have you ever been worried about waking up from your sleep, only to find that your living room and kitchen have been converted into a new highway?

It can happen, although probably not while you sleep lah. If you buy land or a house, you’ll probably get a title or any other document that guarantees your land is truly yours, and nobody can dispute that. However, most indigenous people in Malaysia can’t feel that secure.

If you read Cilisos on the regular, you might have remembered our feature on how the Temiars in Kelantan had to fight off thugs with CHAINSAWS from taking away their land, but sadly that’s just one case out of hundreds. The truth is, land conflicts between indigenous people and the government happen a lot, but recently the Sarawak government took a step towards ending that. How? By amending their Land Code to give more protection to the natives’ customary lands.

Woo hoo! Sounds good right?! However, in a surprising turn of events, hundreds of natives took to the streets to protest the amendment within days after it cleared the state assembly. Eh? If it protects their land, why are they protesting it? Well, if you followed the news, perhaps this one didn’t take you by surprise, as this issue started, like, two years ago. But first…

The unique way indigenous people define their land (and how the law didn’t agree with them)

Due to the various indigenous cultures in Sarawak, there are several ways you can own land. For the Bidayuh people, for example, whoever clears a patch of land first have rights to it, and it can be inherited by future generations. Customary land measurements tend to be imprecise (“my land is, like, from this patch of bamboos to that river’s edge over there”), and there are several customary classifications of land that are important to this story:

- the pemakai menoa, an area around the main house that varies in size (one source said half a day’s journey), and everything in it.

- the pulau galau, communal forests situated within a house’s pemakai menoa, where natives get forest produce. May be shared among several houses.

- the temuda, basically any piece of cleared and cultivated land. Or farmlands.

So with that out of the way, let’s look at a court case between a headman in Kanowit, Sandah anak Tandau, plus seven other native land owners against the Sarawak state government in 2016. What happened back then, was that a timber company received the license from the state government to log an area in Kanowit, and part of that area happened to be customarily owned by Sandah and co.

The logging company had the license to log some 2,712 hectares of forest that happened to be within Sandah and co’s pemakai menoa territory, making the forest a pulau galau, and hence part of their customary land. While several written laws, including the Sarawak Land Code, had recognized land acquired under native customs as belonging to the natives, the court had interpreted that only the temuda (cultivated land) counts as native land, and not the pemakai menoa and pulau galau.

Sandah and co lost the case, and the decision became a judicial precedent (the decision courts have to follow for similar cases in the future), meaning that any native whose pemakai menoa and pulau galau are (or would be) threatened can give up on going to court over it, as legally those don’t belong to the natives any more.

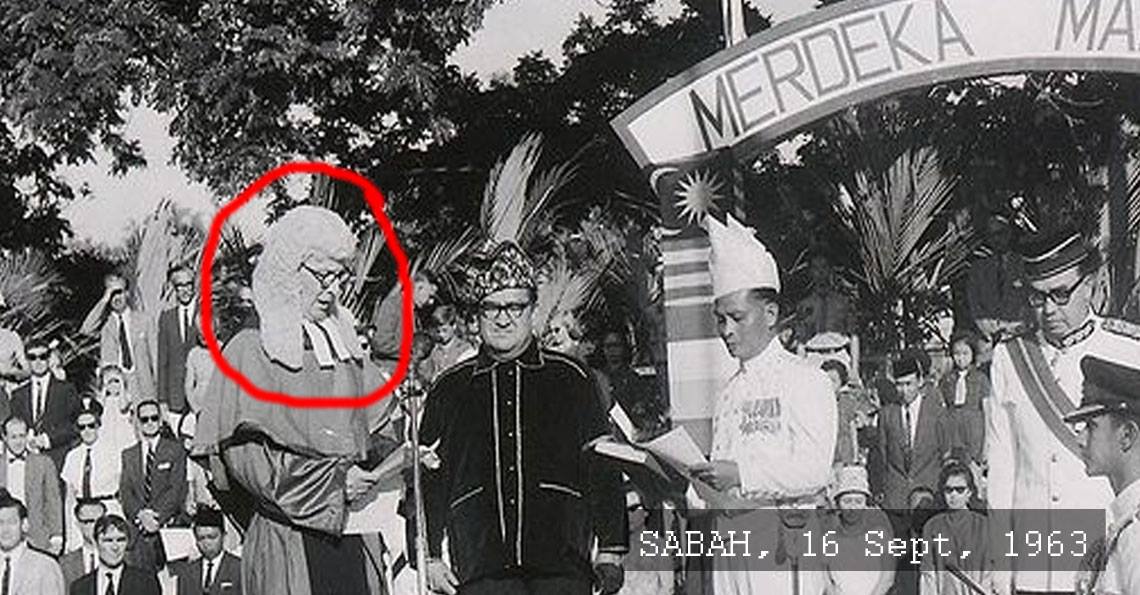

Ever since then, the natives have been pressuring the government to do something about it, and…

The government did address the problem, but raised another

The case outcome was like a slap to the face of many native landowners, and they demanded that their native customary rights be given the force of law by the government. After a year of nothing concrete, in November last year the natives held a rally, and they gave the state gomen three months to respond to their demands by amending the Land Code, addressing several things like recognizing the pemakai menoa and pulau galau as native customary lands and not making land titles immune against them.

A few days after that, the Sarawak state government announced that they will draw up comprehensive amendments to the Land Code, and a Native Customary Rights task force will look at the issues. Fast forward to earlier this month, a draft of the Bill to amend the Land Code came out.

Among other things, it addressed the problem of different definitions of the pemakai menoa and pulau galau by referring to those areas (along with the temuda and others) collectively as ‘Native Territorial Domain‘ (NTD). It also provided the possibility of NTD owners to get a permanent title that are indefeasible, or unchallenged by anyone.

However, native social rights groups and community leaders who read the draft were not pleased, as the Bill also limited the area of NTDs to only 500 hectares. Also, a Kafkaesque nightmare waits for those who wished to apply: in order to get titles for the NTDs, an application will have to be made through the Superintendent of Land and Surveys, then approved by the Director of Land and Surveys, and if rejected, have to be appealed against the relevant Minister.

After much haggling and debating in the State Assembly, the Land Code (Amendment) Bill was finally passed on July 12, but with two changes to the original draft: the size limit of NTDs was increased from 500 to 1,000 hectares, and in addition to granting permanent land titles, it will also be free of charge, without premium or rent. But they still can’t sell off the land.

“The ‘Pemakai Menoa’ size limit had now been increased to 1,000 ha and the title granted in perpetuity and free of premium, rent or other charges… Of course, we will not allow them to be sold off. If the owners concerned want to develop them for oil palm or rubber plantations they should inform the government,” – Datuk Amar Douglas Uggah Embas, to the Borneo Post.

While this may seem like a step up…

The main problem still seems far from being solved

Soon after the Bill was passed by the state assembly, some native groups took to the streets in protest, as they still can’t accept its ‘rushed’ passing despite their earlier protests against it. Some of the natives even found the need to apply for rights over their own land degrading, while others see it as purposely making it harder for the natives in favor of the logging companies.

“Our control over the Pemakai Menuai and Pulau Galau have been recognized even by the colonial British rulers. Now, we have been placed under the control of the State Land and Survey director. We have to apply to the director for the right to use our very own territorial communal land. We are effectively being categorized as squatters in the communal land we inherited from our ancestors. This is an act of gross injustice.” – Michael Jok, secretary-general of Society for Rights of Indigenous Peoples of Sarawak (SCRIPS), to the Star.

In response to the protests, Uggah had asked native community leaders to help the government explain the benefits of the amendments to the people, and he regretted that the amendments hadn’t been well-understood and politicized to cause anxiety to the community. However, it might just boil down to a long history of clashing interests.

A 2011 article published by the American Geographical Society have observed that the government wanted the indigenous people (along with their land and resources) to be assimilated into ‘modern’ society, and the indigenous communities wanted their share in the economic developments as well. However, the government’s means to achieve that restricted the indigenous people’s freedom, and the indigenous people were not prepared to give up their lands, cultures and identities in exchange for economic development.

The paper also observed that the indigenous communities tried to push back the negative side-effects of development projects by forming NGOs and going to court over their grievances, but what they really wanted was recognition of their rights to land. However, their own political weakness and the government’s repressive laws stood in their way. The American Geographical Society‘s words, not ours.

If not for the date, the paper might have just described the current situation in Sarawak. The indigenous people still want their terms of pemakai menoa and pulau galau to be recognized fairly according to their customs, but the government had grouped them all under Native Territorial Domains. The government wants to give the natives actual land titles for their lands, but the natives are refusing to do things the government’s way. The native social groups claimed that they were not properly consulted prior to the Bill’s tabling, yet the state had mentioned that the Bill was a result of more than one year of discussions with community leaders and Dayak professionals.

So, until both sides understand and admit the real problem and are willing to compromise, it could seem that land conflicts in Sarawak will continue to exist and be a tool for politics.

- 1.1KShares

- Facebook1.0K

- Twitter8

- LinkedIn5

- Email13

- WhatsApp71