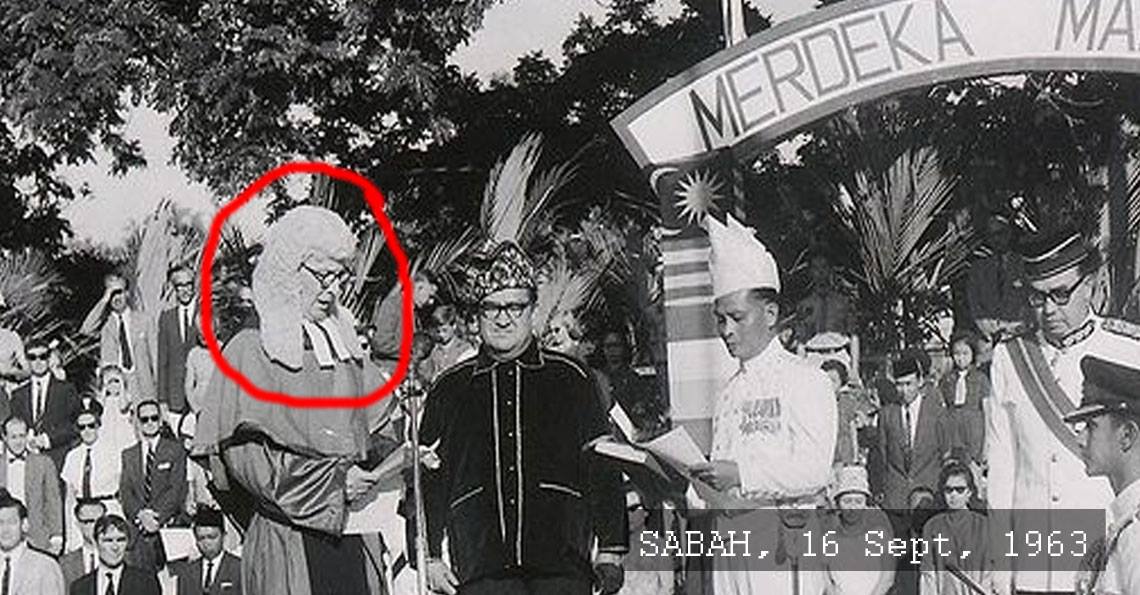

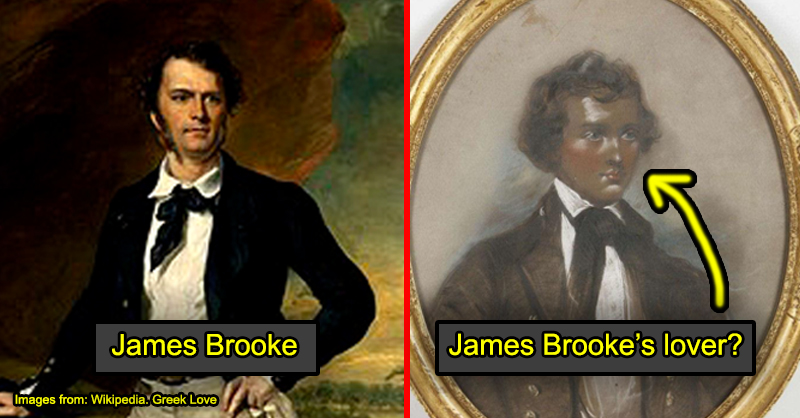

Historians claim James Brooke was gay. Was this 16 year-old boy his lover?

- 198Shares

- Facebook142

- Twitter8

- LinkedIn5

- Email8

- WhatsApp34

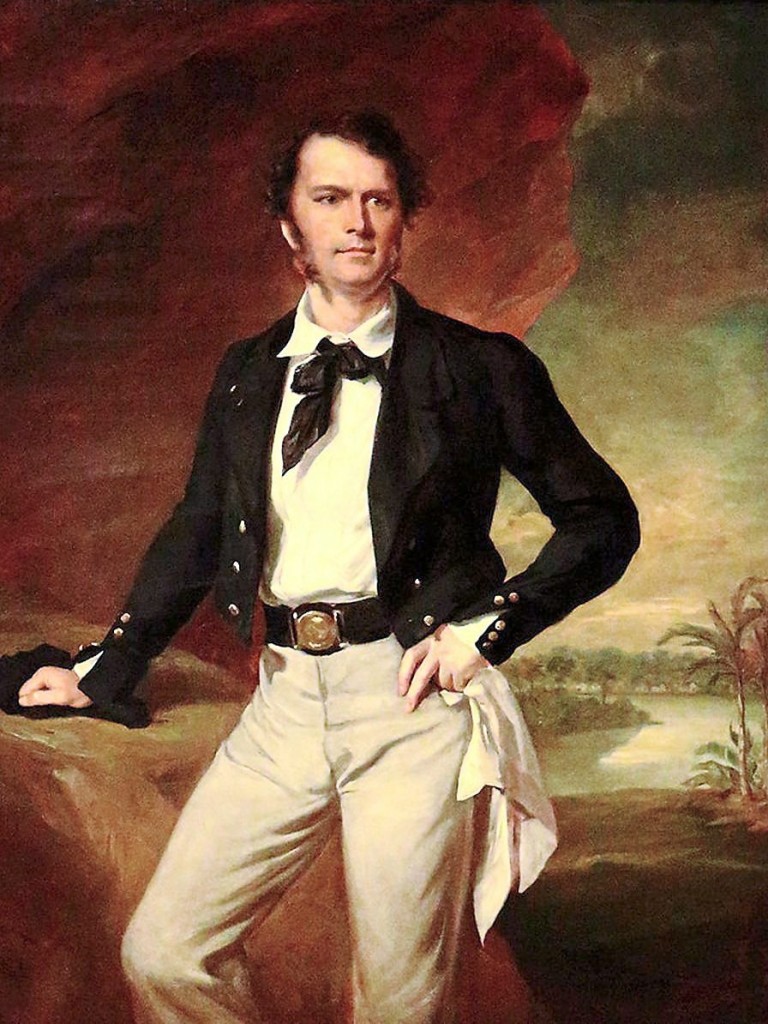

While researching on the history of Sarawak, we stumbled upon a very interesting theory regarding the White Rajah of Sarawak, James Brooke: apparently, the swashbuckling pirate hunter so influential in the histories of both Sarawak and Brunei might have been a closet homosexual.

And no, we aren’t making this up; it’s been claimed by several notable people in fact.

Brooke allegedly showed no interest in women

Believe it or not, a man of James Brooke’s stature was never officially married (though some sources claim he was married to a Bruneian princess according to Muslim rites).

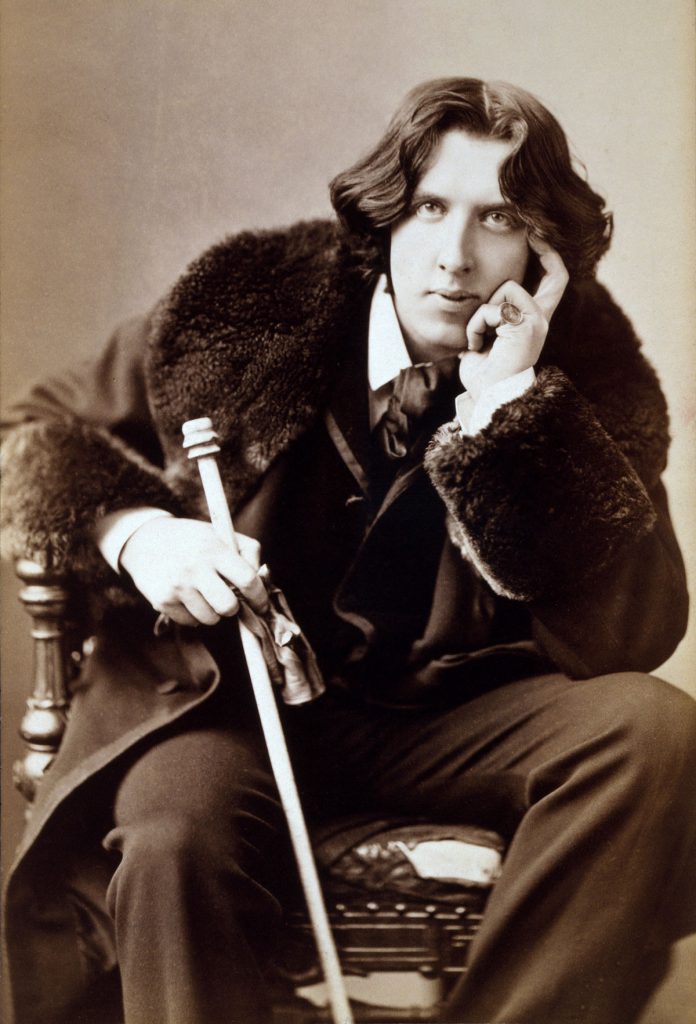

In 1800s Victorian England, homosexuality was still criminalized (playwright Oscar Wilde being the most famous example), but attitudes towards it were warming somewhat, and it was starting to become increasingly tolerated.

In James Brooke’s case, he certainly never admitted to it outright, but he was said to have ‘an embarrassingly total lack of physical interest in women’. What’s more is that he left a trail of clues hinting at his alleged sexual orientation. It’s claimed that he had a ‘close relationship’ with a Sarawakian prince named Badruddin, about whom he wrote:

“My love for him was deeper than anyone I knew.” – James Brooke

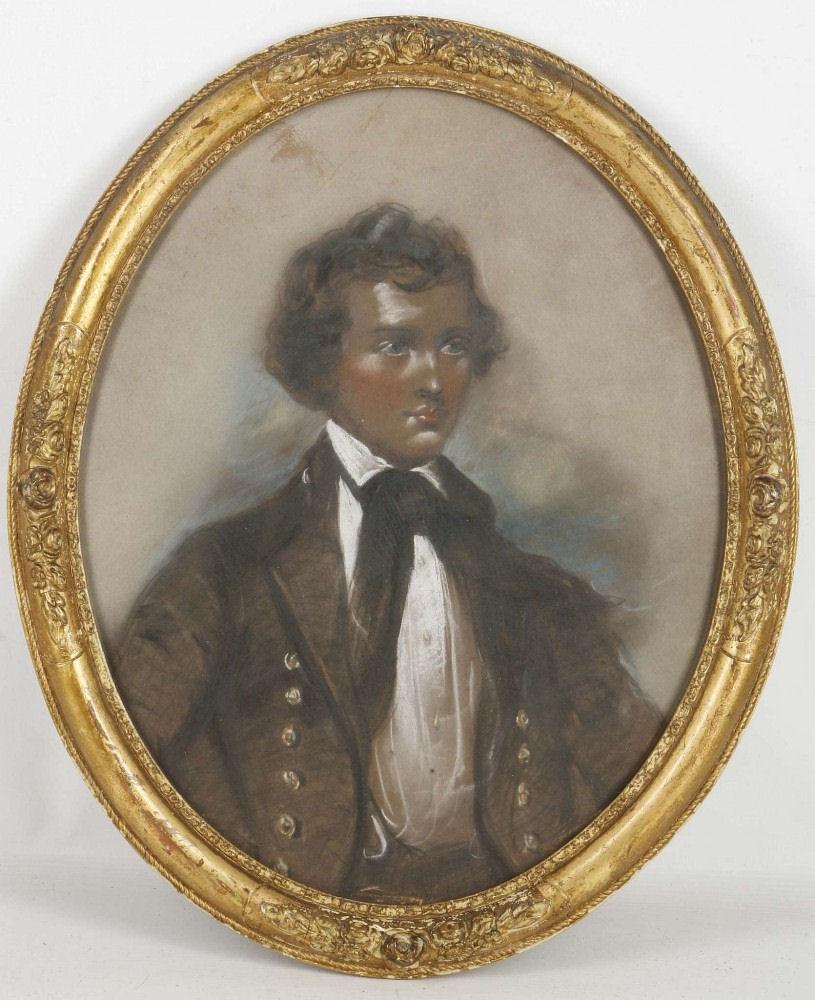

He also allegedly had close relationships with young (like, teenage young) midshipmen, most notably Charles Grant, a 16 year-old midshipman he befriended and later made his personal aide. Romantic or not, Brooke is said to have been so attached to Grant that he showered him with letters, poems, and expensive gifts, even giving him a nickname: ‘Hoddy Doddy’. It’s said that Brooke’s feelings were ‘reciprocated by Grant’.

Of course, there are two sides to every story, and Brooke’s is no different.

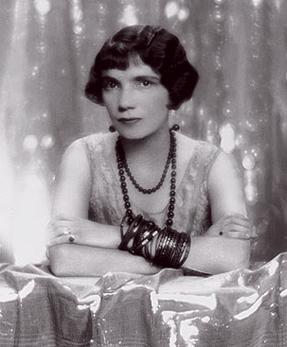

Brooke’s great-grandniece Sylvia claims he was shot in the balls

Yes, literally. Apparently, Sylvia, wife of the third and last Rajah of Sarawak Charles Vyner Brooke responded strongly to homosexual allegations of her great-granduncle, claiming that he was not actually gay, but had in fact sustained a gunshot wound to the testicles during the 1825 Anglo-Burmese War, an injury which had ‘forever stilled his sexual passions’ (though biographer R. Reece claims this testicular injury never happened).

Either that, or James Brooke might just have been very ‘bro’ with his bros, since male relationships during the Victorian Era were common and usually platonic, hence it was suggested that Brooke might just have preferred the company of males without sexual connotations. Of course, that doesn’t mean that he didn’t have any female friends, because he had plenty (though it’s said that these relationships were extremely platonic in nature):

“He was one of those men who are able to be the close and intimate friends of women without a tinge of love-making.” – Kegan Paul, nephew of Mrs. Littlehales, an early playmate of James Brooke

To top it all off, Brooke admitted that he had fathered an illegitimate son with an unknown woman, even including this son in his will.

Based on all this information, it’s difficult to conclude if he was indeed gay, but what we found was that…

Quite a few historians have allegedly tried to ‘force’ this gay theory

Interestingly, it was only in the mid-late 20th century that this theory appears to have surfaced, as the subject of his homosexuality seems to have been largely ignored or downplayed until then. Regarding Brooke’s letters to Charles Grant, it was said by historian Nicholas Tarling in 1982 that they ‘are those of a kind uncle‘, leaning towards the explanation that Brooke did not act on his homosexuality, at least to public knowledge.

It was only in 1988 that a more detailed allegation surfaced in “This peculiar acuteness of feeling’: James Brooke and the enactment of desire” by Dr J. H. Walker, but this was criticized for exaggeration and seeing sexual attraction where there was none. Perhaps the most balanced view comes from biographer Nigel Barley, who wrote:

“Attraction is not seduction, nor is seduction love. To equate them is to reduce the rich, polyphonic music of James’s emotional life to a single note… And let us not pretend that we can easily read the discourse of Victorian sexuality, which is a language very different from our own.” – Nigel Barley, The White Rajah: A Biography of Sir James Brooke (2002)

But possibly the most interesting thing about all of this, is that:

“… nobody seems to have cared — not the then-Sultan, not the Sultan’s uncle Muda Hassim, not even Brooke’s enemies.. It seems his sexuality was left a matter for his private life alone.” – erinambersmith, writer for Medium.com

- 198Shares

- Facebook142

- Twitter8

- LinkedIn5

- Email8

- WhatsApp34