The multiracial history of Batu Caves that your Sejarah lessons never taught you

- 395Shares

- Facebook343

- Twitter8

- LinkedIn6

- Email7

- WhatsApp29

Well, it sure isn’t Malaysia if we’re not enjoying a stretch of holidays or a random day off each month. And this time around, it’s Thaipusam.

There are many stories about the origins of Thaipusam, but the most famous one is of Lord Murugan (the god worshipped during Thaipusam) defeating a horde of demons who were harassing his devotees. He fought and he won, and ever since then he’s been celebrated as a symbol of good triumphing over evil. To his devotees, he’s an almighty figure bathed in gold, both in status and appearance.

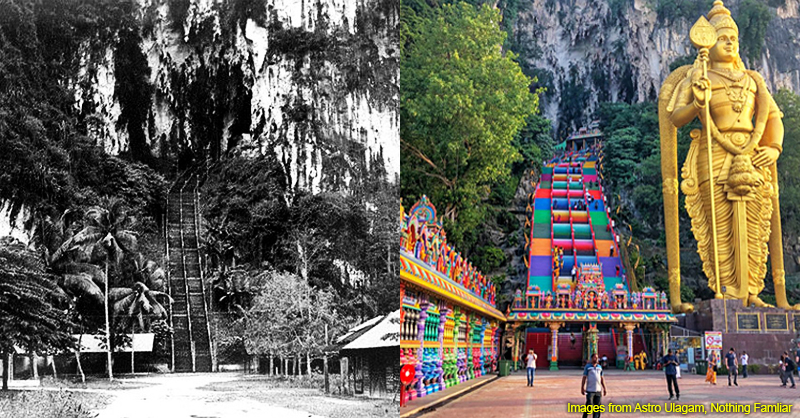

You’ve likely seen Lord Murugan in all his golden glory and it’s that huge statue that sits at the foot of Batu Caves. In fact, the entire Batu Caves complex is dedicated to Lord Murugan. But what’s interesting is that the place hasn’t always been a Hindu shrine – it had gone through several changes of hand before becoming the iconic tourist spot it is today.

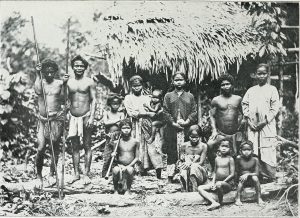

The Orang Asli used the caves for shelter

We’re talking prior to the 1860s here, since there were no official records of when it started. Back then, the Temuan Orang Asli took refuge in the caves during bad weather and between hunting trips. If you didn’t know, Batu Caves isn’t just one cave with one temple, it’s a network of caves and chambers spanning over 2 km long. But as far as anyone could tell, the Temuan people didn’t really explore the caves; they just hung around the entrances.

For context, the Temuan tribe had originally settled in an area called Pertak, a forest reserve around the Selangor-Pahang border. And according to Google Maps, it’s not thaaaaaaaat far from Batu Caves, especially when you consider the fact that a single hunting trip sometimes took days.

The Temuan tribe is also known for passing down Malaysian folklore and though it’s unclear if this is one of theirs, there’s a lore associated with Batu Caves. You guys remember that Si Tenggang anak derhaka story? It’s about a poor kid who joined a ship crew, then worked his way up the ranks. He returned to his village a wealthy man but refused to acknowledge his poor, unsightly parents. Distraught, his mother cursed him, and Si Tenggang was turned into stone along with his ship.

And here’s the cool part–it’s said that Batu Caves was originally known as Kapal Tanggang, being the ship that was turned to stone in the Si Tenggang story.

Chinese settlers used the bat droppings there as fertilizer

If you’ve been to Batu Caves you’d know it’s filled with monkeys and snakes and many, many bats. Turns out, the bats had been there since before Mahathir’s grandpa saw a kavadi.

Quick Sejarah recap for all you people who only memorize Malaysian history for SPM 🥲, the British had already invaded Malaya by 1860, and they brought in workers from China and India. We mostly know that the Chinese were brought in to work our mines, but in actuality they were not only miners but also laborers, merchants and planters. And it was the planters who frequented the caves, extracting guano (fancy science name for bat poo) to fertilize their vegetable farms.

But things were still pretty lowkey at the time. It was only the locals or people familiar with the area who had gone into the caves and no one had truly trekked deep into the complex yet. That was until…

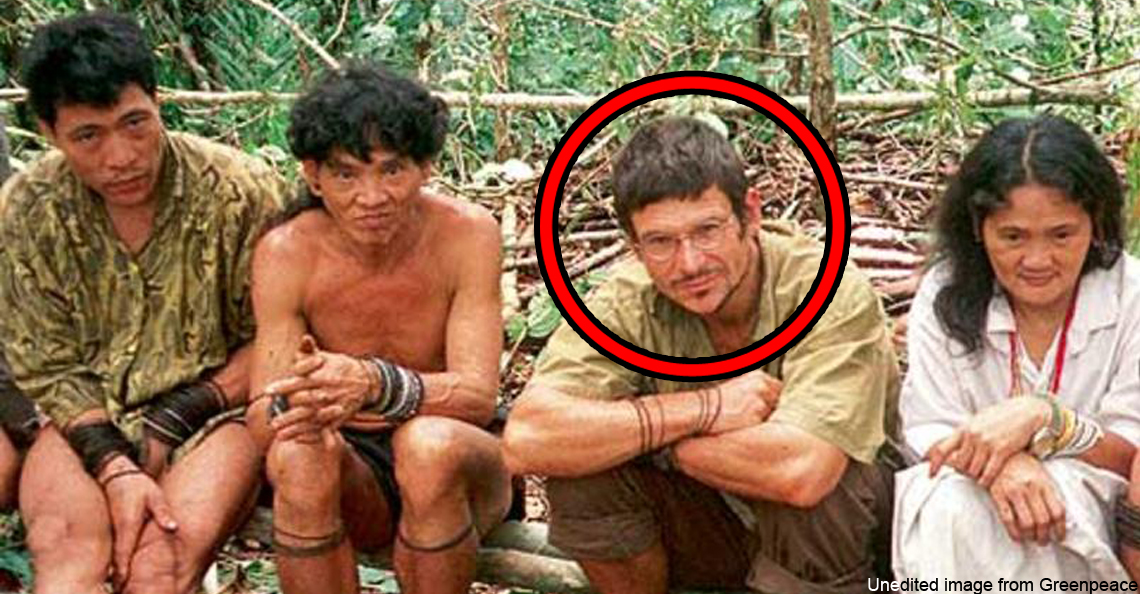

A couple of Mat Sallehs discovered the caves and told the world

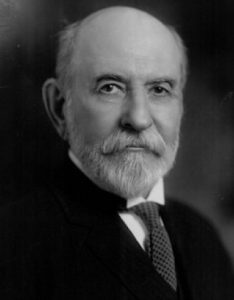

Fast forward to 1878, Englishmen Daly and Syers, as well as American William Hornaday came across Batu Caves and put it down on record. William Hornaday particularly, is credited as the man who officially discovered the caves.

Hornaday was a zoologist and had travelled to Malaya and Borneo to observe our Southeast Asian jungles. He then wrote about his experience in his book, Two Years in the Jungle where he made several mentions of Batu Caves with some real funky 19th century spelling.

“All these caves are about three miles east of Batu, and nine from Kwala Lumpor, in a northerly direction. The whole hill is a solid mass of white crystalline and its greatest height is about three hundred feet,” – excerpt from William Hornaday, Two Years in the Jungle (1885)

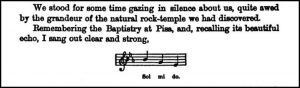

He also tested out the acoustics at Batu Caves and was very impressed.

And no, it wasn’t a temple at that point. Hornaday thought the roof of the cave looked so much like St. Peter’s Cathedral in Rome that he deemed it a place of worship. He said if he could name it himself, he would call it Cathedral Cave.

A local Indian promoted Batu Caves as a place of worship

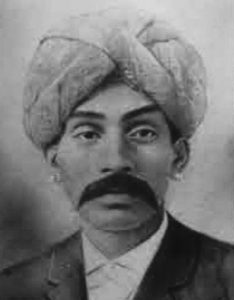

In the 1890s, K. Thamboosamy Pillai was a prominent figure in the local Indian community. He was vocal in his politics, adept in his business dealings and was also the founder of the modern-day Batu Caves.

The story was that he was looking for a suitable place to worship Lord Murugan when he stumbled upon the caves. One of the defining features of Lord Murugan is his spear (called a Vel) that was gifted to him by his mother, the goddess Parvati. And it was the shape of this Vel that Pillai saw in the cave entrance. Inspired by this vision, Pillai built a temple in Lord Murugan’s honour and installed a sacred statue of him. And in 1892, the first Thaipusam at Batu Caves was celebrated.

Slowly after that, renovations were made to improve the area. Wooden stairs were constructed in 1920 so we can only assume devotees were proficient rock climbers before that.

In 1930, the wooden steps were replaced with concrete ones. In 2006, the golden Murugan statue was unveiled and it was, at the time, the tallest statue of a Hindu deity worldwide. And finally in 2018, all 272 of those concrete steps got a rainbow makeover.

And that’s pretty much where we are today. Looking back at Batu Caves’ colourful history, it’s really the perfect match to Thaipusam, which on multiple occasions has been described as a rich and colourful festival. Also a bit of trivia to end this article, it’s believed that Lord Murugan’s favourite colours are orange and yellow which is why devotees dress brightly in celebration.

- 395Shares

- Facebook343

- Twitter8

- LinkedIn6

- Email7

- WhatsApp29