The surprising story of how JKR workers fought the communists in Malaya

- 2.4KShares

- Facebook2.3K

- Twitter14

- LinkedIn15

- Email27

- WhatsApp85

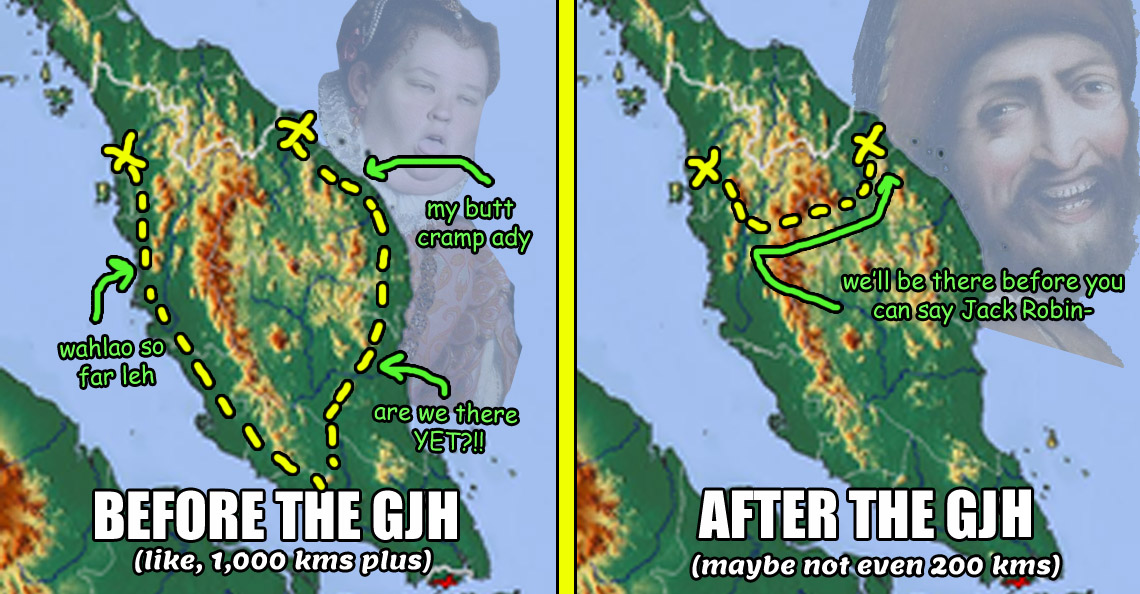

If you’re in Kelantan and had to drive over to Kedah, chances are you’ll be taking the Gerik-Jeli Highway (GJH). It’s a scenic 123-kilometer long road that considerably reduces the driving distance between the northeastern part of the Peninsular and the East Coast, and it starts in Gerik, Perak and ends in Jeli, Kelantan. Or it starts in Jeli. Heck, technically it starts at both sides, but we’ll get to that later.

Opened to the public on this date (1st of July) 41 years ago (1982), this scenic route took the Jabatan Kerja Raya (JKR) 15 years to complete and cost more than RM200 million. You’ve probably heard tales of elephants and ghosts and landslides from people who took the route on the regular, but have you heard the reason behind the road’s construction in the first place? Sure, to connect the east and west, duh. But there’s another reason behind it, and it had something to do with the communist insurgency back then.

Malaya was plagued by communists then, and Gerik seemed to bear the brunt

Perhaps the bloodiest conflict Malaya/Malaysia has had since its independence had something to do with the Communist Insurgencies, and it happened twice. The first one was between 1948 and 1960, and it involved the British fighting the military arm of the Malayan Communist Party (MCP) at that time. Basically, the communists wanted to overthrow the British, so the two sides duked it out, resulting in great losses to the British, the communists and civilians caught between them.

When Malaya got her independence in 1957, the main cause of the communists’ unrest (the British) was gone. The communists retreated in 1960 to the Malaysian-Thailand border to lick their wounds, regroup, and train their guerrilla tactics by watching the Vietnam war. A relatively peaceful 8 years passed, but in 1968 they resurfaced and killed 17 security personnel at the town of Kroh (present-day Pengkalan Hulu, Perak), marking the beginning of the second Communist Insurgency in Malaysia.

Due to their proximity to the Malaysian-Thailand border, the town of Gerik and the surrounding areas were heavily dangerous at that time, with Gerik being classified as a black area (heavily patrolled) up until the emergency ended in 1989. A former Special Constable even recounted how Gerik was the most dangerous district during the whole affair.

“I joined the SC in 1955 with a friend who was also stationed in several other districts in turn. Around 10,000 SCs in Perak and thousands of civilians were killed by communists with no mercy.” – Abdul Rani Che Lah, Former Hulu Perak Chief Special Constable (SC), translated from Harian Metro.

But how did a band of communists manage to plague the Malaysian government for so long? Well, it had something to do with their guerrilla tactics, and the Malaysian government had to come up with a tactic of their own to combat that.

The Malaysian government fought the communists’ hit-and-run warfare… with development.

If you’re a part of a small group planning to overthrow a government, a good tactic to use is guerrilla warfare. Guerrilla warfare (not to be confused with gorilla warfare) involves a relatively smaller force harassing a larger force until they surrender, through tactics like destroying infrastructure, ambushing small groups of enemy troops, sabotage, hit-and-run, and basically any tactic that can damage a bigger enemy over time while minimizing their own losses.

“The enemy advances, we retreat; the enemy camps, we harass; the enemy tires, we attack; the enemy retreats, we pursue.” – Mao Zedong, in his book “A Single Spark Can Start a Prairie Fire“.

Sounds like a pain, but that’s not all. In 1960s Malaya, there were plenty of jungles and mountains, which translated to a huge advantage for the guerrillas: their small groups can move easier in the jungle, and there were lots of places to hide, regroup, and launch ambushes from. Also, as with the norm of most guerrilla groups, Malaya’s communists also had close ties to the society at that time, relying among members of the public who sympathize with their agenda (or were indoctrinated) for logistical support and indirectly using them as a sort of human shield.

How do you fight against such an enemy? The Malaysian government at that time realized that brute force alone was not enough. They must have the support of the public as well, and so by drawing from the experience from the first Malayan Emergency and the experience of American forces in Vietnam, the Program Keselamatan dan Pembangunan (KESBAN) came into being.

In essence, one of the ideas behind KESBAN was that communism thrived on poverty, so to make the people less likely to support the communists, they have to eliminate poverty by developing infrastructures and policies. One such project was the building of the Gerik-Jeli Highway, which was planned to kill several birds with one stone. The construction of the road, besides easing the public’s and Malaysian forces’ movement, also has the added effect of cutting the communists off from their bases in Thailand.

Originally, the road was planned by Tun Abdul Razak to start from Butterworth and end in Kelantan, however…

The construction of the road was a lot harder than anticipated

Sometime after Tun Abdul Razak announced the road, the original plan had changed and the starting point moved from Butterworth to Gerik. Despite the shortened goal, the task was no less daunting. To turn a stretch of wilderness into a road, the JKR workers had to first map out where the road is going to be without GPS and Google Maps. After that, it was decided that construction will be done starting from both ends (Gerik and Jeli) simultaneously.

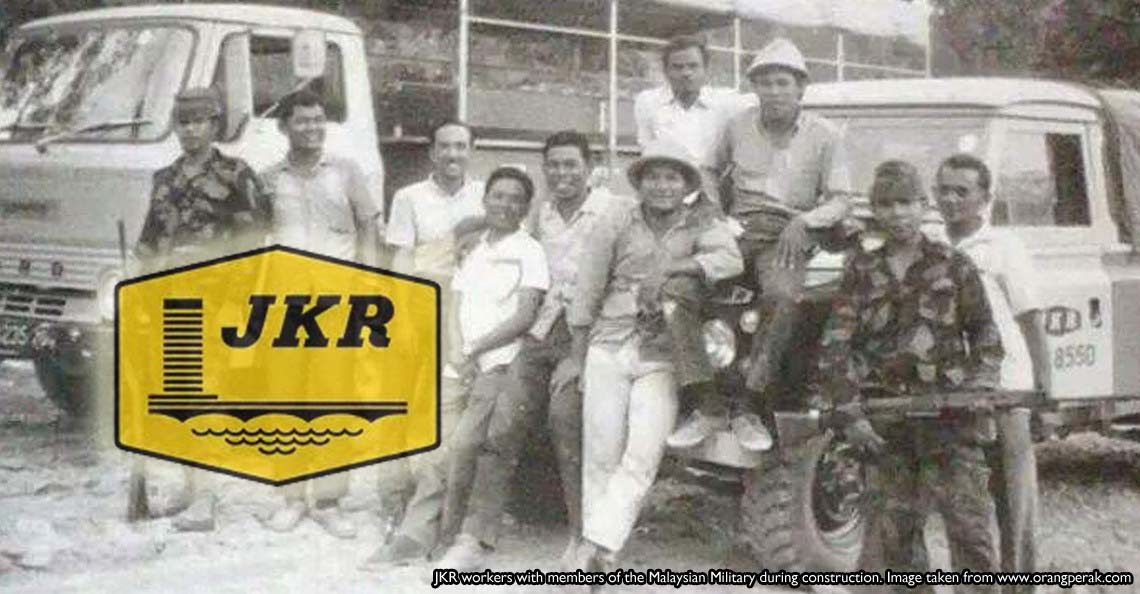

Two base camps were initially set up to house the workers and their families at Gerik and Jeli, and every day the workers will move from those to the active construction site, moving farther in as more of the road was completed.

The first thing to do was clear the dense forests enough to lay down a foundation, and the foundation had been another headache. Good roads tend to be more or less flat, and the only way to connect the east coast and the west in the northern Peninsular was by crossing several mountain ranges and the valleys in between. The most prominent of these would be the Banjaran Titiwangsa, a long and high mound of granite and layered rock that stretches from the Thai border all the way to Malacca.

To turn this roller-coaster of a path into a more or less level road that even a beat-up Nissan Sunny can traverse, the JKR workers had to cut out 27.5 million cubic meters of earth, with almost 4 million cubic meters of it being rock, requiring a lot of drilling and blasting, and use those to fill up some valleys, some of which are over 100 meters deep. Malaysia’s natural climate had been another challenge: with the monsoon season and heavy rains, time available for construction was reduced to 10 months a year.

All these factors made the job seem tough enough, but there’s a way bigger challenge waiting for the JKR workers…

The communist terrorists weren’t happy with the construction, and they’ve tried everything to stop it

As if it wasn’t a hard enough task to begin with, workers were often harassed by wildlife and the communists, with the latter turning out to the biggest threat to the job. By disseminating propaganda through leaflets and radio broadcasts, the communists turned a portion of the public against the workers, inciting them to hate and discourage the workers for following the directives of Tun Abdul Razak. When calling names failed to stop the construction, the communists decided to take matters into their own hands and begun actively sabotaging and disrupting the project, attacking the workers and destroying their heavy machinery.

Despite the military closely monitoring the project (standing guard while they worked and placing military posts at every kilometer of the road), two major incidents happened. The first one happened on the 23rd of May 1974, when the communists launched a sabotage operation and managed to destroy more than 60 construction machines. Mohd Bakri Md Nali (64), former JKR worker who was there when the attack happened, recalled how the attack continued throughout the night.

“It happened at around eight in the night, when me and several other workers were on the way to the construction site. Before we could get there, an explosion suddenly happened. We were shocked by the situation, but we’re told by the military to stay where we were to avoid unwanted incidents. It was worrying, as the explosions continued all through the night.

“Every worker was assembled at the Gerik Base Camp. Since a large number of the machinery were destroyed in the explosions, road construction works had to be delayed for some time.” – Mohd Bakri Md Nali, translated from Utusan Online.

The second incident happened a few months later (27th August), and this time, the communists managed to kill 3 JKR workers in an ambush on their way from the Gerik Base Camp to Banding. Little was known about the fallen workers, except their names: Ismail, Husin and Ali.

“Once we’ve reached kilometer 178 on the route, the workers were attacked and shot, killing three of them and wounding several other workers and soldiers,” – Mohamed Jahari Kadir, also a former JKR worker, translated from Utusan Online.

These were but two big incidents, and throughout the construction many lives were lost not just through communist attacks, but workplace accidents as well. The communists did not let up the pressure for the duration of the construction. Security continued to be tightened, and the military and police continued their communist-hunting operations (the Ops Pagar). Despite these conditions, the workers continued with their task, but the original deadline had to be extended and the budget ballooned up, from the initial RM85 million to a total of RM396 million.

Despite the hardships and deaths, the JKR workers, the military and the police did not give up, and on the 1st of July, 1982, the highway was finally opened to the public.

The insurgencies ended decades ago, but the route remains until this very day.

Although finishing the highway could be counted as a win, there was still the main war to be won. The government remained vigilant, and made it so that people who wanted to use the road had to apply for a security permit beforehand, and even if you had one you can only traverse the route before 6 p.m. Military posts were placed along the highway and at the entry points, and those without a permit or trying to enter after 6 will be asked to turn back.

While construction went on, the communists were growing weaker. Internal discord broke them up, factions distrusted each other, and the communists remaining in the fight came to the realization that they could not win with their current strength. They also realized that they may have no place to go if the war ended, so on the 2nd of December 1989 the remaining communists agreed to sign the Peace Agreement of Hat Yai with both the Malaysian and Thailand governments.

This agreement allowed the communists to return to whichever states they came from (or resettled in Peace Villages along the Thai border) and get the government to stop hunting them, in return for them laying down their weapons, stopping their militant activities and pledging their loyalties to the Agong, among other things. With everything settled, the agreement marks the end of the Communist Insurgency in Malaysia, as well as the usage of permits and curfews on the Gerik-Jeli Highway.

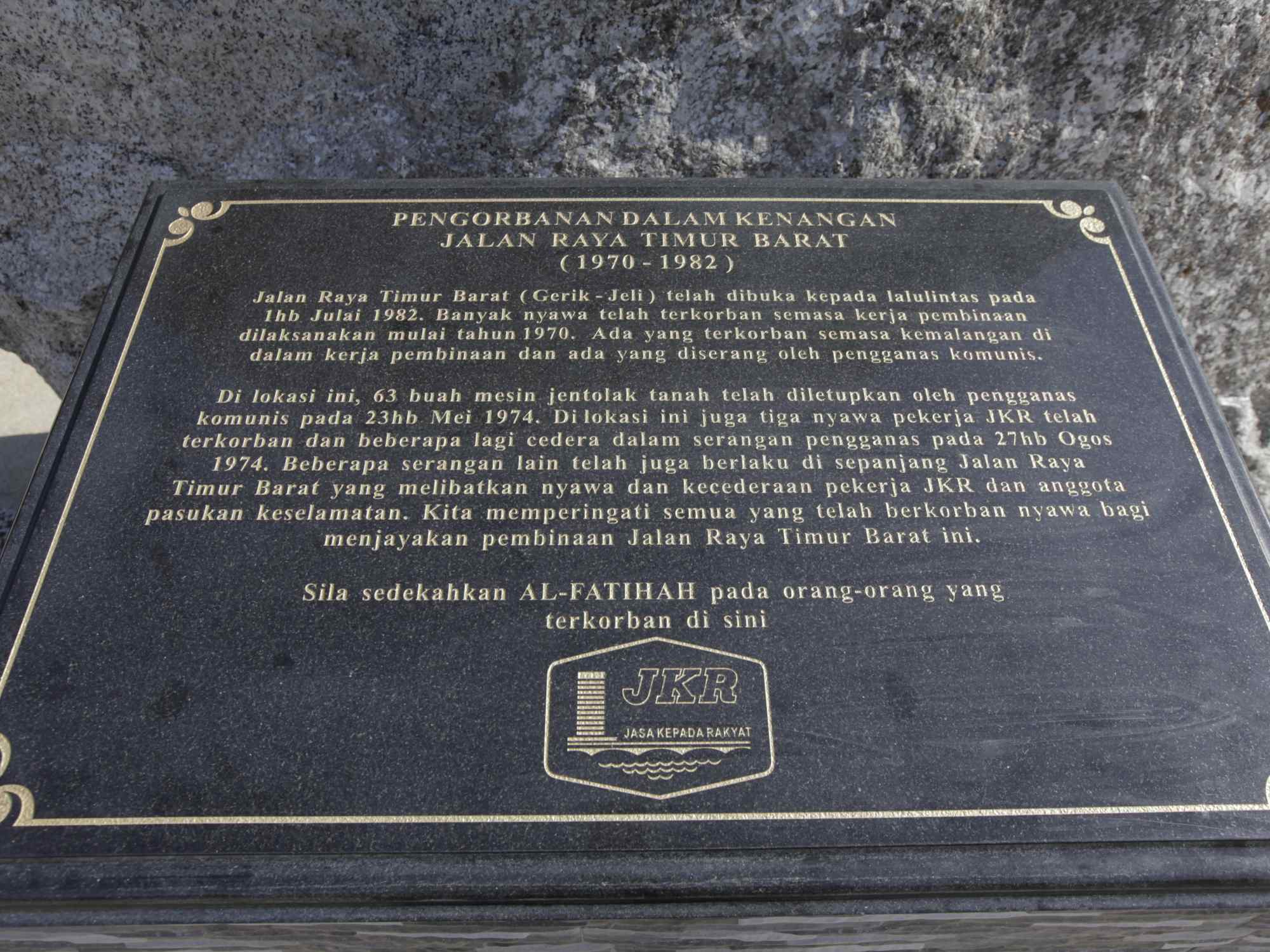

Today, several reminders of the past exist along the highway, if one cared to look for them. One of them is a monument built by the JKR in 1994 to remember the service and the sacrifice of the JKR workers involved in the GJH’s construction.

“The East West Highway (Gerik–Jeli) was opened to traffic on 1st July 1982. Many lives have been lost during the construction which was implemented in 1970. Some have died during work accidents and some were attacked by communist terrorists.

“At this location, about 63 bulldozers were blown up by the communist terrorists on 23 May 1974. At this location also three JKR workers were killed and several others wounded in an ambush on 27th August 1974. Several other attacks have occurred along the highway involving the JKR workers and security forces. We commemorate those who have sacrificed their lives for the construction of the East West Highway.

“Please recite AL-FATIHAH for those who lost their lives here.” – Inscription on the monument titled “Pengorbanan Dalam Kenangan”, translated by Wikipedia.

Although perhaps not many knew of its history, the Gerik-Jeli Highway itself can be said to be a monument to today’s Malaysia, planned and built by the JKR, for Malaysians. It’s a product of over a decade of blood, sweat and tears of our older generations who hoped of a better future, and it should be a reminder of what we can accomplish through perseverance.

- 2.4KShares

- Facebook2.3K

- Twitter14

- LinkedIn15

- Email27

- WhatsApp85