The 1989 deal that ended communist conflict in M’sia… actually allows Chin Peng’s return

- 1.2KShares

- Facebook1.2K

- Twitter3

- LinkedIn1

- Email1

- WhatsApp19

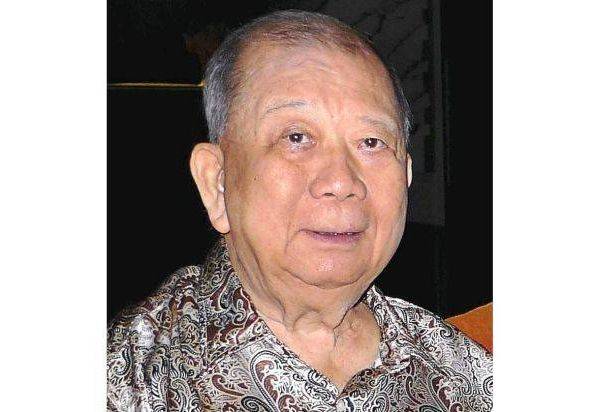

Even from beyond the grave, the late Malayan Communist Party (MCP) leader Chin Peng still managed to cause a stir among Malaysians when his ashes were allegedly brought back by a local group and scattered in his hometown in Perak in a ceremony last month:

“We are only informing the public now just to let people know what we have done.” – Chai Kan Fook, leader of committee who handled his remains

Although this isn’t the first time the issue of Chin Peng’s ashes has been brought up, the move has proved extremely controversial, with some people such as Dr. M defending the move, while several others have slammed it as being ‘insensitive’, ‘hurtful to the feelings of Malaysians’, and even ‘illegal’. In fact, the supposed ‘illegality’ of the return of Chin Peng’s ashes have now made it a police issue, and the group responsible has been called in for questioning (more on this later).

However, among everything that’s been said on the issue so far, there was one in particular that caught our eye, mainly because it referenced a peace agreement that supposedly allows the return of the ashes:

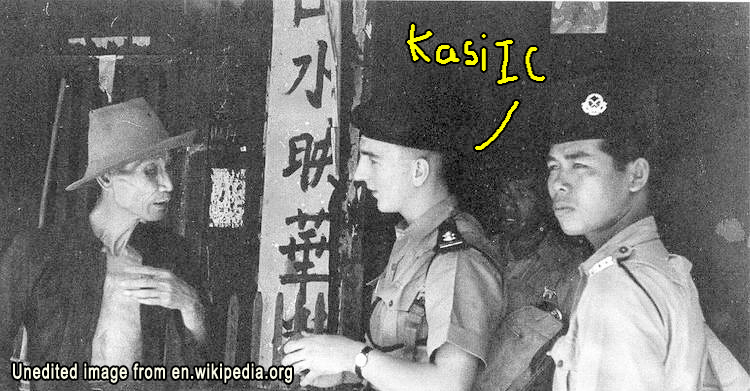

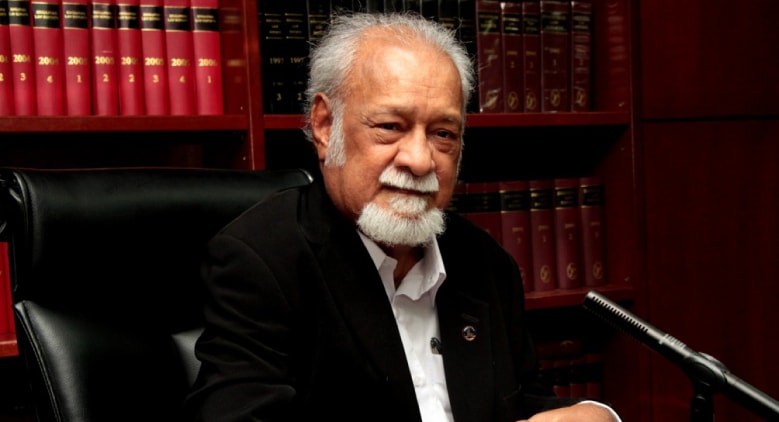

“The peace agreement itself showed that the country wanted to let bygones be bygones and move forward after peace was achieved… All Malaysians should look at this issue based on the existence of the Hat Yai Peace Accord signed with CPM in 1989.” – Tan Sri Rahim Noor, former Inspector-General of Police

So we decided to take a closer look at this peace accord, and here’s what we found out…

The Hat Yai Peace Agreement was meant to ensure fair treatment for the defeated Communists

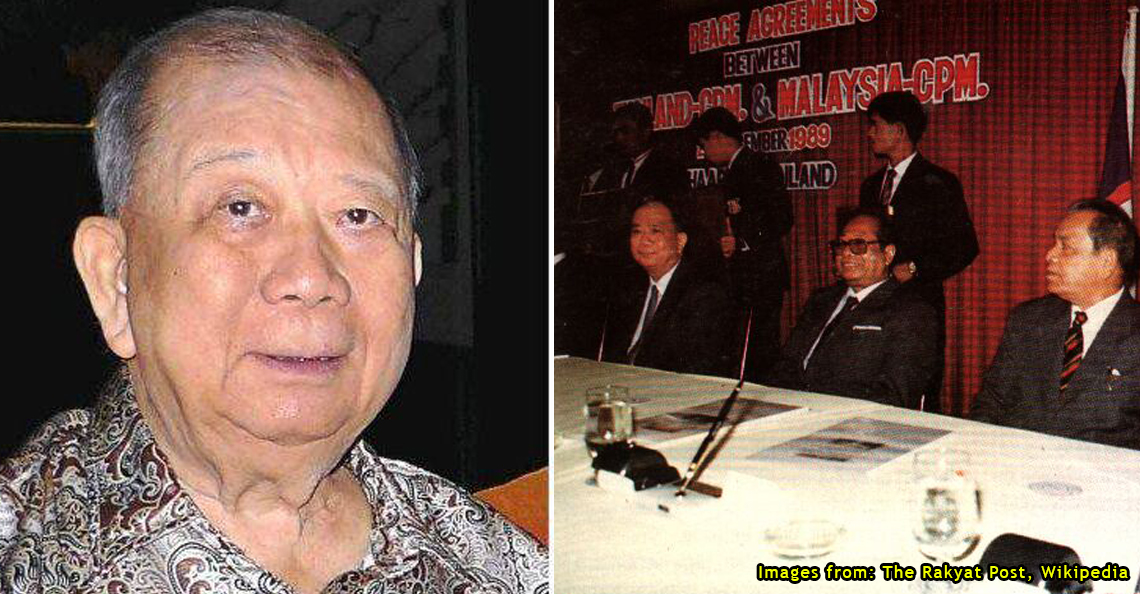

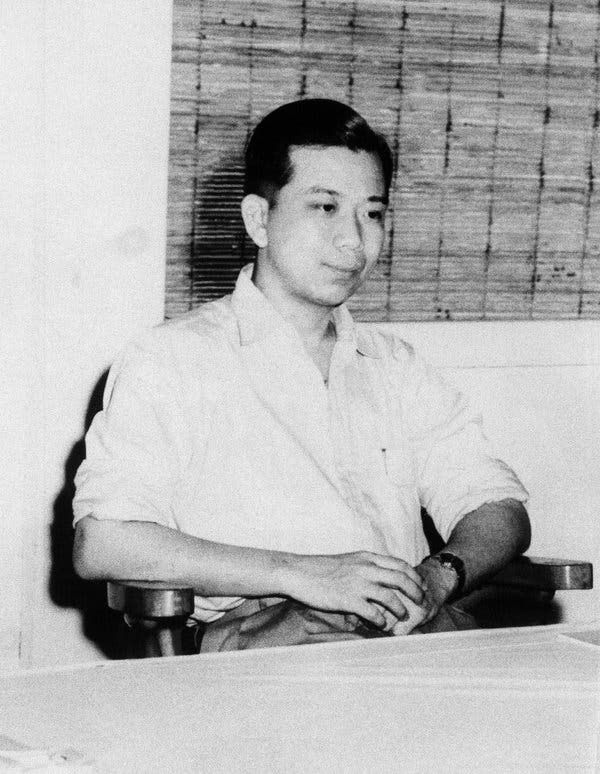

Following the collapse of the Communist Bloc in 1989 and continued losses in Malaysia, Chin Peng began considering a peace settlement between the Malaysian government and his own Malayan Communist Party. So on the 2nd of December 1989, the ‘Agreement Between the Government of Malaysia and the Malayan Communist Party to Terminate Hostilities’ was held in Hat Yai, Thailand.

Besides ceasing hostilities and having the MCP swear allegiance to the Agong, the agreement was also supposed to help the Communists get back to civilian life, allowing them to not only return to Malaysia, but also to participate in local politics:

“The government of Malaysia will in due course allow former members of the disbanded armed units … to freely participate in political activities within (the) framework of the federal constitution and the laws of Malaysia.” – joint communique from the governments of Malaysia and Thailand

Meanwhile, the Communists pledged to ‘terminate all armed activities and bring peace to the entire Thai-Malaysian border and Malaysia’, as well as to ‘respect the laws of the two countries and participate in social and economic development‘:

″We shall disband our armed units and destroy our weapons to show our sincerity to terminate the armed struggle.” – Chin Peng

We could go on more about it and what not, but long story short is this: the terms of the Hat Yai peace treaty pretty much allowed all Communist Party leaders to return to Malaysia. And this includes Chin Peng. However, Chin Peng never got to return to Malaysia in his lifetime after that day, despite the fact that other members of the MCP had no trouble doing so.

A few reasons have been pointed out, but it appears as tho one big reason behind Chin Peng’s difficulty in baliking kampung is…

Chin Peng couldn’t prove he was Malaysian

The question of why Chin Peng was denied a homecoming despite the Hat Yai Agreement seemingly allowing him to do so is not an easy one to answer. The ‘official’ reason is that Chin Peng could not prove in court that he was a Malaysian citizen.

In 2009, Chin Peng submitted an application to the Malaysian government to allow him to return, but the Federal Court ruled against his application based on that reason. This was in spite of Chin himself maintaining that his birth certificate had been seized by police during a raid in 1948.

The fact that Chin Peng chose to remain in Thailand following the one year grace period to return to Malaysia (as stipulated in the Hat Yai agreement) further complicates things.

Malaysian Armed Forces Veterans Association (PVATM) president Datuk Sharuddin Omar claims that Chin Peng had forfeited his citizenship by choosing to do so, while UMNO leader Mohd Puad Zarkashi said that Chin Peng’s failure to place his name on the list of those who wanted to return to Malaysia suggested that he didn’t actually want to come back:

“This means Chin Peng did not want to return to Malaysia. Perhaps Chin Peng did not wish to fulfil the condition of leaving aside the Communist ideology which rejects the monarchy system.” – Mohd Puad Zarkashi, as quoted from Malaysiakini

Then of course, there are the emotional reasons: a few people, especially veterans like Datuk Sharuddin cited the sensitivities of the Malaysian people regarding the topic, saying that the feelings of the people who fought against the communists might be hurt:

“We have to think about the sensitivity and the sacrifices of our (military) heroes. We have to see first.” – Dato’ Seri Wan Azizah, Deputy Prime Minister

“I used to be a Border Scout and a police officer before, and I surely know how they (security forces and their families) feel right now.” – Datuk Idris Buang, Parti Pesaka Bumiputera Bersatu information chief

With that being said, not everyone in Malaysia has opposed Chin Peng (or his ashes) from returning, especially when you consider that…

Other major Communist leaders actually returned to Malaysia

The deeds of Chin Peng notwithstanding, there are some who are still holding fast to the idea that Chin Peng deserved at least to be allowed to have his ashes scattered on home soil and sea, if only to honour the Hat Yai Peace Agreement.

For example, the late Karpal Singh backed the move following Chin’s death in 2013, saying the government should be ‘cautious’ about the message it was sending by refusing to allow Chin Peng’s ashes to return home. He also rubbished the Federal Court ruling of 2009:

“Many people don’t have birth certificates, but that doesn’t mean he was not a citizen.” – Karpal Singh

The same argument was also raised recently in Parliament by DAP MP Datuk Ngeh Khoo Ham, who questioned the integrity of the previous government for ‘failing to honour an international agreement’, echoing Karpal’s statement that the decision would not reflect kindly upon Malaysia.

Even our Prime Minister Tun Dr. Mahathir himself (who helped draft the Hat Yai Peace Accord) asked why this was even an issue in the first place, citing the examples of senior MCP leaders like Shamsiah Fakeh and Rashid Maidin, whose returns were accepted without question:

“But now, we couldn’t accept Chin Peng simply because he was the leader.” – Tun Dr. Mahathir

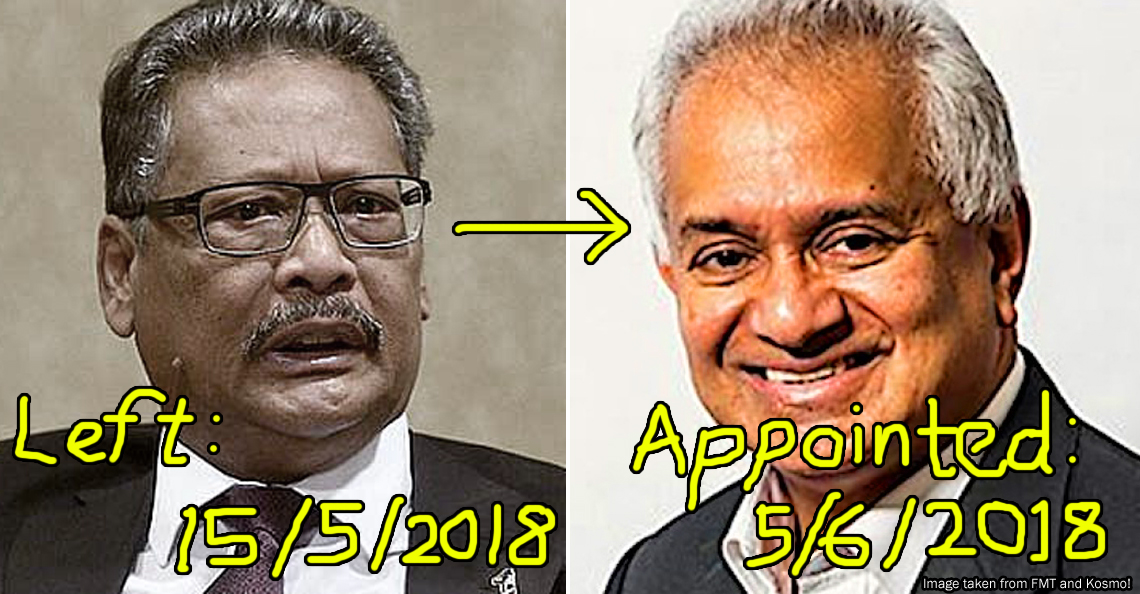

This view was echoed by another individual who was actually present at the Hat Yai Peace Agreement: ex-IGP Rahim Noor, who personally oversaw the fight against Communism in the 80’s as head of Special Branch:

So if Chin Peng was allowed to come back, what is it with all these noises saying that his ashes should not be allowed here?” – Tan Sri Rahim Noor, former Inspector-General of Police

However, the legality of Chin’s ashes, status of his citizenship, and sensitivities of the people aside, there’s also the fact that the group that brought Chin Peng’s ashes back could have been committing a separate, unrelated offense, because…

You can get arrested for smuggling human ashes

It’s a lil weird, but basically even if there was no issue with the return of Chin Peng’s ashes to home soil, the group responsible could still find themselves in trouble for breaching Customs guidelines on the bringing in of human ashes, which state that:

“The person who brings in the urn containing human ash is required to inform and produce the relevant supporting documents (i.e. airway bill/manifest/train load list/letter of release) to the Officer of Customs on duty at the entry point.” – Royal Malaysian Customs Department

This was apparently one of the reasons the issue of Chin Peng’s ashes became a police one, as it is unclear if they had undergone the proper procedures in the first place:

“The question is whether the party concerned had so informed or smuggled it (the ashes) into the country without the knowledge of the authorities. What is certain is that we never knew at all. We only came to know about it after the family or friend had made a statement.” – Tan Sri Muhyiddin Yassin, Home Minister

In fact, the group could find themselves facing a slew of charges besides this, as they are currently also being investigated under:

- Section 504, Penal Code: Intentional insult with intent to provoke a breach of the peace

- Section 505(b), Penal Code: Statements conducing to public mischief

- Section 233, Communications and Multimedia Act 1998: Sharing of offensive and menacing content

Chin Peng’s deeds are not easily forgotten, but a dead man is no danger to anyone

Despite his heartfelt apology to Malaysian citizens before his death, it’s clear that the memories of the Communist Insurgency are still fresh in the minds of some Malaysians, and the pain caused by him and his men is not easily forgotten. All in all, it is estimated that more than 20,000 Malaysians died over a period of four decades fighting the Communist insurgency in Malaysia.

However, an interview with Chin Peng shortly before his death painted a different picture from that of the bloodthirsty tyrant depicted in Malaysian history books; when asked what he would like to do if given the chance to return, he simply said:

“Go to coffeeshop of youth in Sitiawan, have teh and roti kaya. Meet old friends and teachers who would be in their 90s now. Told some still alive. Just want to live a quiet life.” – Chin Peng

Whether this is an attempt at sympathy, just someone genuinely being sentimental in old age, or even (dare we say) the words of a man regretting his past actions; there’s perhaps no argument that Chin Peng continues to pay the price of his actions to this day – whether in history books or in death.

- 1.2KShares

- Facebook1.2K

- Twitter3

- LinkedIn1

- Email1

- WhatsApp19