How do you handle death in a multi-religious family? This winning M’sian film explores that.

- 766Shares

- Facebook722

- Twitter4

- LinkedIn2

- Email13

- WhatsApp25

Unless you’re a super hipster artsy millennial or a car guy with a thing for film, you may not have heard of the BMW Shorties short film competition. Now don’t worry, this article isn’t sponsored – altho if BMW wanna give us money we have no problem with that either. However, this article is about the winner of the 2017 BMW Shorties award, Never Was The Shade, which features two half brothers with different beliefs dealing with with the death of their dad.

You should probably watch the above video as it’s pretty good, like, it did win a short film competition after all. But it’s not just the cinematography or editing that makes the film stand out, but rather the underlying juxtaposition of John, a middle class Chinese man and Arif, a pious Malay man. Both having their own well-meaning intentions on how to deal with their dad’s body involving religious customs and familial traditions, the film touches on a lot of topics many of us would consider taboo and sensitive.

Now when we showed this to the office, there was quite a number of us (read: everyone but this writer) who had no idea what the triangle thing at the end of the film is. So we might as well deal with the elephant in the room, and tell you that…

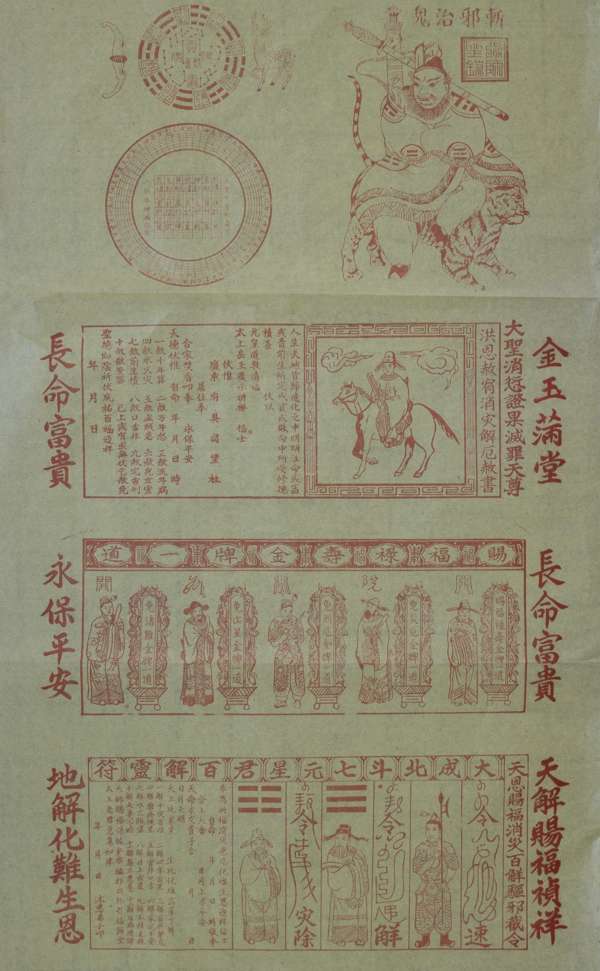

The triangle thing is actually a traditional Chinese paper talisman

Okay we know some of you lazy and didn’t see the whole film, so this is what we’re talking about:

So a super quick synopsis: Arif wants a Muslim funeral, seeing as after John’s mum died, their dad married Arif’s mum and converted to Islam in the process. John’s sister however is in US and won’t make it in time, and John wants to delay the burial. They end up arguing, and the argument only stops when the body is taken away to be readied for the funeral. Later on, Arif discovers that John placed a yellow triangle of paper under their dying dad’s pillow.

That yellow triangle is actually known as a ‘fu’, which is basically a Chinese/Taoist talisman or amulet. It’s a piece of (usually) yellow paper with symbols and prayers written on it, and will have to be used in a ritual of sorts by a Taoist practitioner. There are various versions of it, from talismans for wealth and luck to those for protection and happiness. We also managed to get in touch with the director, who mentions that growing up, he himself had one of these talismans.

“The talisman – like the one the brother put into the pillow – when I was a child my mum went to the temple to get one of these talismans to put into my own pillow or wallet,” – Lim Kean Hian

As for why Lim used the talisman, he explains that Arif taking the talisman in the end symbolises the tolerance that the two brothers have with each other’s beliefs and customs – John for example allowed Arif bury their dad following Malay customs, despite being ethnically Chinese. Another reason why Lim used the Chinese ‘fu’ talisman instead of other more common religious symbols is that it’s a great way to get people to know more about these lesser known customs.

Growing up, we all probably know some of the more common customs each ethnicity and religion has, such as Friday prayers, Sunday mass, and so forth. But Lim says that the lack of understanding about the talisman – even among some Chinese people – is a sign that despite the six decades that we’ve all lived in the same country, there remains a severe lack of mutual understanding among the different groups of people.

Lim adds that people still don’t know enough about other cultures, and that with his short film, people will hopefully end up finding out more about the talisman and other traditions and superstitions, and that it may become a good start towards us opening up to each other.

Of course, it’s probably still a good thing to remember that this short film is a work of fiction. That got us thinking then: what would happen if this situation happened in real life?

The short film was actually inspired by real life events

Yep, believe it or not, just like King Kong Titanic, Lim says that his film was inspired by a news article he read a few a couple of years back that apparently involved a Chinese dad who had passed away. According to Lim, during the wake, the religious authorities popped by and wanted to take the body away because he had allegedly converted to Islam without the family knowing.

Now, we couldn’t actually find the exact case that Lim was talking about, but we did find a super similar case that happened in Penang back in 2014. The state Islamic department had interrupted the Taoist-style funeral of Teoh Cheng Cheng and took the body of the deceased after claiming she had converted to Islam before her death. The family disagreed with burying her in the Muslim way, and it escalated all the way to the court.

While we can never answer for sure as things would always differ on a case by case basis, what we can say is that there seems to be an agreement that the deceased should be buried as quick as possible when following Muslim burial rites. Some do say that there can be a small delay, perhaps for family members to give their last respects, but that there still shouldn’t be too long between the last breath and the burial.

“It is recommended that the deceased be buried as soon as possible without waiting too long for family members that are out there, unless the wait isn’t overtly long,” – Ustadz Ammi Nur Baits, translated from Konsultasi Syariah

The film definitely noted that the need for the dad to be buried quick, and it’s not a surprise, as Lim tells us that he worked on the script with a someone who’s Muslim – despite him doing his own research, he wanted to avoid any possible misconceptions and misunderstandings.

That differs from the Chinese burial rites, where a funeral ceremony can last up to 49 days, with the total mourning period going up to 100 days. So like, that’s a huge difference, but then again, that’s also kinda the reason behind the short film laa.

One stick break easy, many stick hard to break

Like we’ve mentioned earlier, Lim hopes that his film can get some viewers to understand the differences and learn more about each group’s customs and traditions in an open minded manner. He adds that he’s not out to criticise any type of tradition, but rather to get us all to know more about each other, but rather to show that we all have a different point of view but that we can still work things out.

But enough about us. Whadduyu think?

- 766Shares

- Facebook722

- Twitter4

- LinkedIn2

- Email13

- WhatsApp25