There’s been a series of elephant deaths in Sabah. And palm oil may be a cause.

- 2.0KShares

- Facebook2.0K

- Twitter3

- LinkedIn1

- Email1

- WhatsApp6

Sometime at the end of September, anglers fishing at a river in Tawau spotted an elephant carcass floating in the river. Pictures of the carcass made went viral on social media, prompting the authorities to locate the carcass.

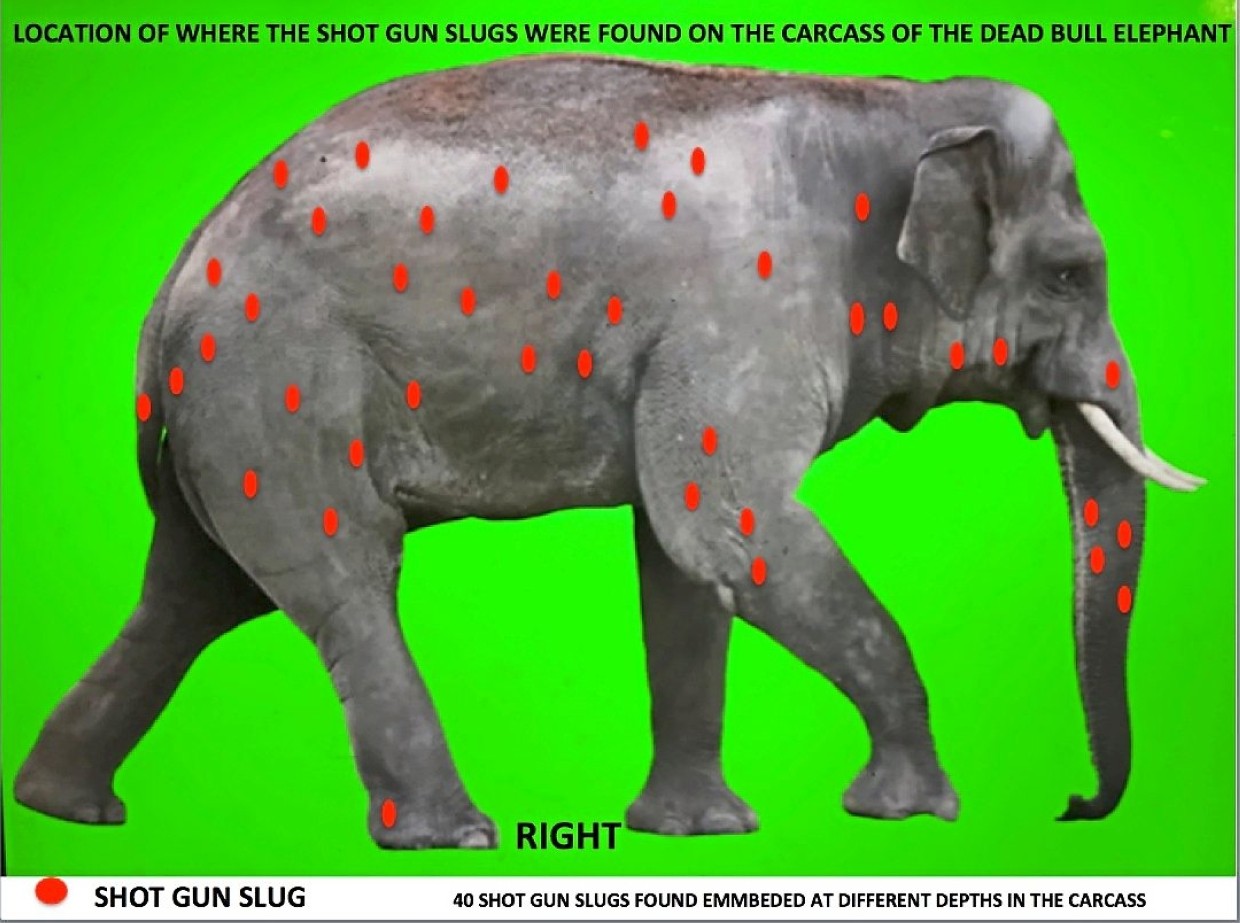

Upon investigation of the body (which has since moved ashore), the cause of death was determined to be due to some 70 shotgun wounds over the animal’s face, back and legs, believed to be shot at close range.

The news shocked and outraged many, but it wasn’t the end of the saga. Since then, another four elephant carcasses showed up in Beluran, Kinabatangan and Lahad Datu, all districts on the east side of Sabah. Except for one, all the elephants died of unnatural causes, either from being shot at, poisoned, or being trapped in a mud-filled ditch. And most, if not all of them, were found in or near oil palm plantations.

By now, you might have put two and two together and guessed what happened to these elephants, but we have to stress that as of the time of writing, investigations are still ongoing, so let’s not jump to conclusions yet. At any rate, Sabah’s Deputy Chief Minister Datuk Christina Liew had denied rumors of a cover up for the culprits responsible, particularly those in oil palm plantations.

Regardless of whether or not there’s a cover up as alleged, it is an interesting link to explore, as…

Oil palm plantations might be a big factor behind these elephant deaths (and many others)

Including the five cases we mentioned earlier, this year alone there has been 23 elephant deaths in Sabah. That averages out to about two dead elephants per month, right around the same rate as the recently reported going-ons. This is actually a big problem, as the elephants in Sabah are from an endangered subspecies of Asian elephants (Elephas maximus) called Borneo pygmy elephants.

Besides being distinguishable by their gentle natures, cute baby faces, plump bellies, oversized ears and tails so long that sometimes they drag on the ground as they walk, they are only found in Borneo (mostly Sabah) with an estimated 1,500 of their kind remaining in the wild.

As for why they’re being killed so frequently, it’s a result of a kind of conflict that’s so common, people termed it as Human-Elephant Conflict (HEC). HEC had been reported in Malaya since the early 1900s, but as more and more of their habitat are being cleared to make way for plantations, settlements and roads, there are more instances where people and wild elephants can meet today than back then.

And unlike conflicts with wild boars (rated as the most troublesome by Malaysian farmers) or long-tailed macaques, people can stand to lose a lot more from HECs. According to WWF, elephants can eat up to 450kg of food a day. Being messy eaters (uprooting and scattering as much as they eat), a single elephant can decimate a hectare of crops in a very short time. It is quoted that oil palm plantations and timber estates in Riau, Indonesia lose USD105 million every year from elephant damage.

We’re not singling out palm oil plantations as the only factor of HEC, but it should be noted that palm oil estates are especially attractive to elephants. The link between HEC and palm oil plantations have often been observed, and according to Jan Vertefeuille, a member of a team who came to study elephants in Sabah back in 2005,

“Growing palm oil trees next to a forest is like dangling candy before a child. The elephants can’t resist it,” – Jan Vertefeuille, of WWF-USA, as quoted by NBC News.

Sabah also has the biggest acreage of oil palm of any state in Malaysia, and it is said that oil palm makes up 45% of the total land area in Kinabatangan alone (2015 figures). Even states on the Peninsular experience HEC as well, with 3 elephants poisoned to death near an oil palm plantation in Johor back in June, for example.

With HEC being such a long-standing issue, you might be interested to know that…

The law provides a way for plantations to kill elephants legally, but with very specific conditions

At least, on the Peninsular, anyway. For the legal aspect of killing elephants to protect a plantation, we couldn’t find anything in Sabah’s Wildlife Conservation Enactment, but for cases on the Peninsular, the Wildlife Conservation Act 2010 (Act 716) had that exact scenario figured out. Section 54 basically says that you may kill the wildlife that is (or is about to) damaging your crops, provided that you tried to scare it off first, but have failed to do so. Once you’ve killed the offending wildlife, you have to report the incident’s details to an officer as soon as possible.

However, there’s a catch. Basically, the idea behind letting people kill or capture the offending wildlife is to prevent potential or further damage to the crops, so if you kill the wildlife after the damage was done (revenge killing), you could face a fine of up to RM10,000 or be jailed for up to six months.

On a more preventive note, agricultural companies sometimes rely on deep ditches dug around the perimeter of plantations to discourage elephants from crossing over. However, it’s not a flawless method, as some elephants were seen to use their front legs to partly fill up the trench with soil, then simply walking through. In one of the recent cases where an elephant calf was found dead in a muddy ditch, it is believed that the calf may have been stepped on by the some of its herd trying to climb out, leading to its death.

Due to our climate having frequent rains, ditches don’t last long, as their dirt walls sort of dissolve after a while. FELDA, for one, discontinued using trenches back in the 1970s as it was too expensive and too much work to maintain the trenches.

For a while, the trend was electric fences. To reduce the number of human-elephant conflict cases, in 2011 the Perhilitan had announced the development of the Sistem Pagar Eletrik Gajah (Elephant Electric Fence System, SPEG), a four-year project that saw the development and maintenance of some 300 kilometers of electric fence in projects scattered around the Peninsular. It showed results, though; there was a 49% drop in elephant cases from 2011 to 2015, when compared to four years prior.

That was a step up from HEC management from back in the 50s, when the main approach to these conflicts is culling as the Wildlife staff at that time lack the training and resources to do much else when confronted with elephant cases. Today, culling is seen as a last resort. Electric fences and translocation of elephants – capturing rogue elephants and moving them far away from human-infested areas – are considerably less lethal to elephants.

However, these methods can be costly. The SPEG project was reported to have cost RM27.4 million, and it is said that it may cost up to RM30,000 to translocate a single elephant. The most popular way seems to be drive shooting, which is basically shooting firearms to scare off elephants, followed by monitoring of the area. Still, it should be noted that these are mostly gleaned from Peninsular sources, so how will Sabah address their elephant issue?

With the recent deaths, Sabah is starting to look seriously into a plan to save their elephants

Sabah was said to have already completed the paper work for a 10-year action plan to increase conservation efforts for their elephants, and it is planned to be presented to the Cabinet by year’s end for approval. However, in light of the recent deaths, Datuk Christina Liew from earlier had said that she will push for its implementation even without the green light. Besides focusing on elephant conservation and protection, the Sabah Elephant Conservation Action Plan 2020-2030 will also research the possibility of helping them reproduce.

Besides that, Sabah is also planning to increase the number of forest rangers and veterinarians to help in the rescue and treatment of elephants they catch in HEC cases, as well as looking into amending their Wildlife Conservation Enactment to make land owners accountable for dead elephants found on or near their land.

“We only have about 60 rangers and 14 offices to cover vast areas of forest reserves. This is not enough. Very often, we receive an alert that some elephants are destroying crops in a plantation. By the time our rangers arrive, the animals have already destroyed the crops and disappeared or they have been poisoned or killed. With additional rangers and veterinarians, we can rescue and treat the elephants,” – Datuk Christina Liew, to FMT.

But the government isn’t the only one concerned. To minimize instances of HEC, some oil palm plantations in Kinabatangan are working together with a French environmental NGO known as HUTAN to establish an elephant corridor. The corridor, planned to link a plantation regularly visited by elephants to the Kinabatangan Wildlife Sanctuary, will involve a 100-meter wide and 3 km long corridor. According to Dr Isabelle Lackman, HUTAN’s director,

“We hope the establishment of this pilot corridor project will provide a comfortable and safer route for the elephants. We also hope that by this, the elephants would be able to roam along the corridor and not in the other parts of the plantation so that crop damage could be reduced,” – Dr Isabelle Lackman, as reported by Malay Mail.

One plantation company was said to allow elephants to use their plantation as a route to look for food by not putting up fences in most areas. Other companies have also chipped in to the cause, by organizing various awareness programs on elephant conservation for their staff as well as students.

While tragic, it can be said that the dark cloud of the elephant deaths does have a silver lining, in that it brings this long-standing issue to the forefront. While the Sabah state government had found it hard to find a concrete solution for HEC in the past, with a 10-year plan in the works and cooperation from responsible plantation owners, the future’s looking sunny for Sabah’s unique elephants.

- 2.0KShares

- Facebook2.0K

- Twitter3

- LinkedIn1

- Email1

- WhatsApp6