Here’s how a muddy island in Johor caused drama between the federal gomen and Johor royalty.

- 438Shares

- Facebook401

- Twitter6

- LinkedIn6

- Email7

- WhatsApp18

Another day, another controversy here in our peaceful country. This time, it involves a muddy island that no one lives on, but is apparently important enough to cause tension between the federal government and Johor’s royalty.

In very simple terms, Pulau Kukup, an island off the coast of Johor, had recently became the property of the Sultan of Johor. This particularly juicy bit of information got some politicians, lawyers and environmentalists protesting the move and voicing out their dissatisfactions over the whole matter. At the time of writing, people are still bickering about it, with people from the federal government insisting that the move be Ctrl+Z’d, and Johor basically going ‘nuh-uh’.

But what’s the big fuss anyway? As it turns out…

Pulau Kukup can be said to be an international treasure

After the tsunami incident in 2004, we’re pretty sure that the average person knows what mangroves are and how they’re important in the event of tsunamis (or for the ecosystem in general). So here’s a quick question for you: can you name the world’s biggest uninhibited mangrove island? Well, we can’t either, but Pulau Kukup is one of the biggest there is.

The name of the island has its roots back when the place was a hotbed of pirating activities, sometime between 1818 and 1824. Pirates would often attack ships that sought shelter there, and according to one version of the story the attacked ships would be capsized by the pirates (diterlingkupkan in Malay), which lends it the name of ‘Kukup’. Others claim that the name comes from ‘gugup‘, the Malay word for anxiety, which people would feel going through there due to the pirates.

Still, ‘kukup’ is the Malay word for mudflats caused by sedimentation, and the 647-hectare island is surrounded by some 800 hectares of mudflats. If you have a hard time visualizing a hectare, imagine a square with 100m sides. That’s a hectare, so the island is pretty big. In fact, it’s so big that if you put together all the mangrove forests in the country, the one on Pulau Kukup will make up three quarters of it.

[Correction 13 Dec: A reader pointed out that Pulau Kukup’s mangroves can’t possibly make up three quarters of the country’s mangroves, and we’re inclined to agree. We assume that the source material actually meant three-quarters of the state’s mangroves instead of three-quarters of the country’s mangroves. Any misunderstanding caused by this is deeply regretted.]

Maybe because of that, it houses a host of vulnerable and near-threatened species, as well as being an important RnR for migratory birds. In 1997 Pulau Kukup was gazetted as a national park, but it wasn’t until 2003 that it was opened to the public. That was also the year the island was recognized as a Ramsar site, which is an area of wetland that is recognized to be of significant value to humanity as a whole.

There are said to be only 2,200 around the world, and Malaysia has seven (three of them in Johor). So with that going on for Pulau Kukup…

Some fear the ownership transfer will affect Pulau Kukup’s mangroves

At the end of October, the Johor state government suddenly published a statement saying that they have cancelled Pulau Kukup’s gazette that gives it the status of national park, and a few days later, the island was registered under Sultan Ibrahim’s name. The sudden announcement of the de-gazetting caused an uproar, with many quarters calling for the de-de-gazetting of the island’s national park status.

Some, like Vincent Chow, vice-president of the Malaysian Nature Society, had feared that besides potentially disrupting the island’s ecology and the nearby fishermen’s livelihood, the de-gazettement would affect the island’s status as a Ramsar site as well. Muhyiddin Yassin, the Home Minister, had also voiced his concerns on the matter, saying that the announcement made him angery.

“Degazetting and transferring the national park into sultanate land is changing the ownership. I appeal to the Sultan to return it to what it was before. Now, any party can go in (to develop).” – Muhyiddin Yassin, as reported by the Straits Times.

Lawyers for Liberty’s N Surendran, on the other hand, had questioned the reason behind the change, saying that the decision is unacceptable and irresponsible. He urged the Menteri Besar and the state exco to disclose who would benefit from the decision, and for the federal government to be involved.

As with many things in Malaysia, the situation turned political for a while, after the state government made a statement saying that the decision was made during the previous government’s tenure in March. However, as pointed out by N Surendran, the actual de-gazetting happened on Sept 24, four months after Pakatan took over the state. This might be a bit confusing, so to recap, in March the decision to de-gazette was made, in September the de-gazetting order happened, and the announcement of the de-gazettement and the transfer of ownership happened in October.

Regardless of all that political drama, what will happen to Pulau Kukup?

Pulau Kukup will be protected by the Sultanate, according to the Sultan

According to statements by the royal family, the change in status is meant to better protect the park. It would seem that even though Pulau Kukup now belongs to the Sultan, it will still be treated as a national park by the state government.

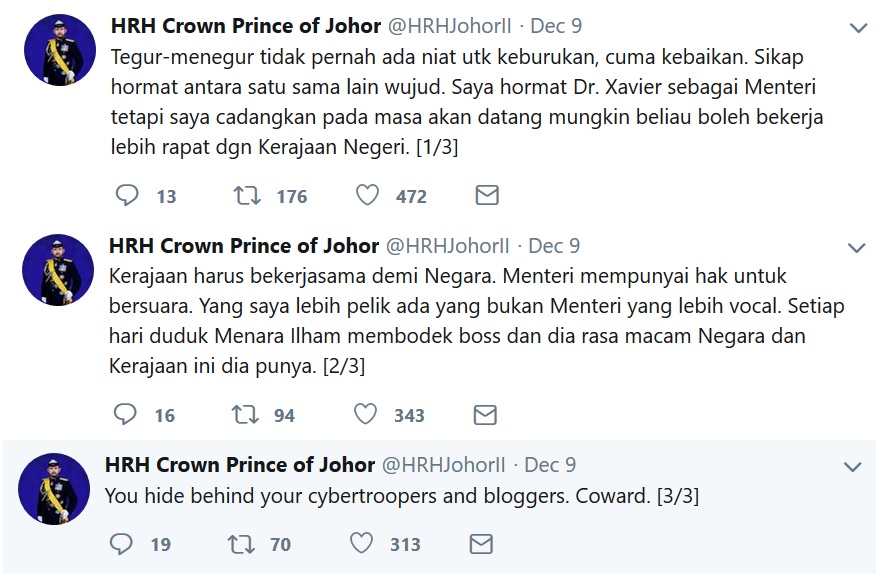

“To better protect all national parks, Sultan Ibrahim decreed that all the national parks be changed to Sultanate land. However, this does not change the status, policies, and usage of the park where it continues to remain a national park status,” – HRH Tunku Ismail Ibni Sultan Ibrahim, the Crown Prince of Johor, as reported by the Star.

HRH Tunku Ismail had said that this mirrors what is currently being practiced in the UK, where although all national parks belong the the Crown, their status remain as that of national parks regarding their policies and usage. Statements by the state’s MB confirm this, and since Pulau Kukup is now Sultanate land, no development will be allowed in the area, as per the Sultanate Enactment 1934.

However, online petitioners (yes, there’s a petition for this) had commented that there is a huge difference between perceived status (sultanate land, but treated as a national park) and actual legal status (re-gazetted as a National Park), as the former will give no legal jurisdiction to enforce the national park laws there. Others have said that the move can’t be fairly compared to what’s going on in UK, as the situations are different.

Regardless of all that, despite the Sultan having made his decision, the Cabinet had insisted that Pulau Kukup remain as a national park for international recognition reasons.

According to them, this is important as

“The change in status of Pulau Kukup (from national park land to Sultanate land) will definitely have an effect on its recognition as an area of international interest as well as Malaysia’s reputation as a country which takes care of biodiversity,” – Dr Xavier Jayakumar, Minister of Water, Land, and Natural Resources, as reported by the Star.

That sparked a fresh episode of drama, with the Johor Crown Prince saying that the matter had already been settled and that outsiders should not meddle in matters that relates to Johor, Tun M insisting that Malaysians and the Federal Government are not outsiders, and the particularly spicy string of tweets we put at the start.

Whew. We’ll leave them to their antics, but the important thing we should ask is…

Why so much fuss about a park’s status, anyway?

Now that we’ve more or less covered the issue at hand, here’s a question for you. Based on your opinion, is it enough to protect Pulau Kukup as a sultanate land, or do we need to legally recognize it as a national park as well?

We’re not saying that there’s no point in recognizing areas as National Parks (recognition brings about awareness, yada yada yada, you know the drill), but consider the case on the Klias National Park in Sabah. It was established in 1978 to protect what was an outstanding mangrove and coastal zone area, but two years after its establishment it was de-gazetted to make way for a forest plantation, as well as a pulp and paper mill. Some two years ago, parts of the Segari Melintang Forest Reserve in Perak was de-gazetted to make way for a quarry.

We’re sure there are more examples, but the point is that in Malaysia, neither National Parks nor forest reserves are really safe. There are provisions in the laws that govern them (Act 226 and Act 313, respectively) that allows the State Authorities to develop, mine or excise (remove) parts of these areas. A historian named Comyn-Platt had observed this attitude towards conservation to stretch all the way back to 1937, when the British encouraged forest reservation programs in Malaya. According to him, certain areas were…

“…allotted to wild life just as long as they are not required for anything else… So long as the cultivator and prospector have no need of them, so long will they remain intact.” – Excerpt from “Conservation: Linking Ecology, Economics and Culture“. Princeton University Press, 2005.

However, some may argue that a National Park will be better protected than a nameless patch of forest, and there will be more hoops to jump through if you want to cut down a National Park. And of course, nature parks can educate the public on the importance of conservation as well, if managed right. Will Pulau Kukup be better off as the Sultan’s property, or as a formal National Park? Disregarding international status and all that, we’d guess that it really depends on how steady the hands that handle it are.

[Update 12 Dec: Based on a statement on the Sultan of Johor’s official Facebook, it would seem that besides being Sultanate land, Pulau Kukup will also stay gazetted as a Johor National Park under the Johor National Park Corporation Enactment 1989.]

[Update 14 Dec: N Surendran, of Lawyers for Liberty, had said that it’s not possible for Pulau Kukup to be both Sultanate land and a gazetted state national park at the same time, as according to Johor’s national park laws the island needs to belong to the state. Therefore, the Sultan needs to relinquish ownership of the land to the state before re-gazetting.]

- 438Shares

- Facebook401

- Twitter6

- LinkedIn6

- Email7

- WhatsApp18